Disruptive Brides and (un)Manly Eunuchs: Reading the Bible as genderqueer to reimagine inclusive faith

On Birds & Kitchen Tables: Conversations of/in the Undercommons

Notes on Eyes and Access: A Transmediale Panel on Sight

Attending conferences such as the 2023 Transmediale A Model A Map A Fiction in Berlin is a type of privilege. In our oversaturated world, it is a privilege to be exposed to people who do the data-sifting for you and collectively fill out and reveal this endless web of connections. By this I mean the shadow power dynamics hidden in the information we consume, spread and eventually integrate as warped common knowledge. So I go and I sit and I listen but in my mind, it is as if I am walking a bridge to a new space, where the dots I am aware of are connected in eye-opening ways and the gaps I was unaware existed between them are filled out. And the feeling I sense is power because there is a power to information and access. That much is clear.

No surprise, then, when I attended the session titled On Seeing Where There’s So Much To See where the participants speak of the power of exposure and the restriction or access to knowledge, space and (re)sources. But this access and visibility are conditioned by the setup behind the seeing. The infrastructure and the technological base and bias of optical media are addressed, which they must be, because what else can be responsible for the gatekeeping of the seeing than the actual design of technologies we use to provide and sharpen sight? Sight is addressed as a technologically enabled and deeply political filter.

Solveig Suess, a researcher and filmmaker, shows archival photographs and part of a film she made, Little Grass. Suess guides us through her research, which is anchored around the intimate and proximate of her mother’s story. Suess’ mother was an optical engineer who developed lenses in China in the 1980s as the wider industry rushed forward to advance optical and network technologies. She speaks of the Chinese trying to catch up and ultimately surpass the West on the linear timeline of ideologically influenced engineering by advancing how far, linearly, as their vision reaches. Suess’ family history is thus placed within the wider geopolitical race to further sight, advance infrared technologies and instruments that make visible what is invisible to the human eye and provide clarity and perception in the darkest of nights.

Suess traces the empty spaces and the absence of vision as well, eloquently subverting the power of reach by feeling around the non-disclosure agreement her mother signed. The narrative of the intimate corresponds with the act of embracing the absence of quantifiable data. This process thickens time and topography and juxtaposes the urgent mechanical, institutional furthering of vision at all costs. I am reminded of how valuable it is to unsettle the close link between vision and militarization. As Paul Virilio writes in his essay Logistics and Perception: “…from the original watchtower through the anchored balloon to the reconnaissance aircraft and remote sensing satellite, one and the same function has been indefinitely repeated, the eye’s function being the function of a weapon.”1

Hence any practices that disrupt the linear logic of observation, visibility and access are counteracting the control and destruction that the advancement of optics implies. What ultimately provides the most control is that which directs, furthers and frames the gaze, be it an instrument or a movement. And this is why the participants of Transmediale were in fact brought together; the ability to trace, reorder and refine, fuse or block, but always redirect the stream of data we swim in as an essential act in subverting the power dynamics of a society where any logical and transparent distribution of (re)sources, sight and information, is a privilege rather than a right.

The collective eeefff, consisting of Dzina Zhuk and Nicolay Spesivtsev, explores the possibilities of algorithmic solidarity but also hacking, strikes and sabotage, challenging the framework and politics of data. Eefff presents a workshop where they interfere with the sensors on train tracks and cause them to come to unexpected stops or stalls, in some ways continuing the Belarusian partisan tradition of sabotaging railway infrastructure.2 This time, we witness an example of grassroots political engineering that makes space for an intimate intervention in a mechanized system through sabotage and pause. And it is funny to me – so fitting – that the train lines would be the target of sabotage because traditionally it is precisely the train that was used as a machine of coverage, speed and linear excavation, colonialism and capitalism. The reframing of temporality and time relations through standstills and accelerations is an act of protest.

Zhuk and Spesivtsev chose the name eeefff because it is the term for a specific colour scheme often used in website design. This name enables them to hide behind the existing search engine recommendation which proposes the colour rather than the collective, as a sort of network curtain. In their work, staying under the radar or not being visible can be an advantage. They speak of digital coalitions, and the myths and glorification of the infrastructure and software of the internet and other network technologies: hard to understand, let alone affect and adapt. They challenge its seemingly inaccessible processes by disturbing the existing cybernetic sequences, making or finding gaps and examining how to inhabit them and by doing so demonstrating insight and access through playful meddling.

The same can be said of the third project discussed, a film by Oleksiy Radynski. He reframes the temporal and geopolitical relations of the new hot Cold War by sifting through and editing a raw video dump of archival footage in connection with the construction and history of the Nord Stream 2. Radynski repurposes the somehow beautiful and washed-out videos of yellow aquatic machinery used to place the more than a thousand kilometres of pipes on the seabed, labs filled with computers that look futuristic and ancient at the same time and politicians being ominous on the tarmac. He speaks of the potential fallacies of data and how science can be twisted and shaped into a need that pushes specific agendas, examining the political implications of the construction of the pipelines, which has roots much further back than imagined.

Radynski reveals West German incentives for providing technology towards the construction of the first pipelines in the 1970s that connect Russian natural gas with Germany. He proposes that the ultimate rise of capitalism in the traditionally communist bloc was closely linked to (the infrastructure that enabled) the personal profits reaped by this historic energy union. Framed within the contemporary context of the Russian attack on Ukraine and the neo-colonial extractivism and fossil fascism3 driving the violence, a sinister image emerges of German political and engineering complacency and entanglement. Again, we are faced with the fact that infrastructure is not neutral, and engineering cannot not be ideologically driven. Thus, the questions and criticism of the debated pipelines.

THE NORD STREAM SABOTAGE – WHO DID IT?

When asked who sabotaged the Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines in September 2022, none of the panellists were able to answer the question. But whoever perpetrated the sabotage was congratulated in a line of the book How To Bomb a Pipeline. Since the Transmediale festival took place in early February 2023, new information surfaced regarding possible culprits. Seymour Hersh, an American award-winning investigative journalist, published an article in which he asserts, according to his solitary, anonymous but well-placed source (note the essential access to the source + extent of sources vision!), that the USA executed the Nord Stream bombings in order to prevent Germany from lifting the sanctions on Russian exports before the dreaded winter of 2022.4

I am interested in this question in the context of optics, access and visibility for obvious reasons; whoever bombed the Nord Stream pipeline proved an evident power of access by being able to somehow plant the bombs and set them off but also prevent any type of surveillance or network technologies to track this movement. Or, according to Hersh, the access was indeed tracked, and perhaps even enabled by multiple governments (Norwegian and Danish) while the traces were guarded against the public.

Although there was a significant amount of residual natural gas in the pipes at the time of the bombings, neither of the pipelines was strictly operational. Nord Stream 1 had already been fully shut off by Russia due to ‘maintenance’, with no immediate plan to reopen it, while Nord Stream 2 had in fact never entered commercial use at all despite its massive capacity (10 times that of the Baltic pipeline, which coincidentally opened just one day after the bombing).

Since the pipelines were not in flow, the 10% increase in gas prices post-pipeline sabotage was short-lived and speculative.5 By the time of the actual explosions in September 2022, the USA had already made quite a profit from the war in Ukraine under the guise of a Western energy union by selling upscale gas to Europe. Exxon Mobile, the largest exporter of American liquified natural gas, had increased its profits by 160% compared to the previous year.6

The intervention was, in my view, in the short term at least, a symbolic demonstration of access and ideological opposition, rather than fully financially motivated. Why else would, according to Hersh, have the plan for the sabotage been confirmed in December 2021, right before the beginning of the (second) invasion? To assert access to the energy lines for the purpose of future infrastructural control with the inevitable result of primarily political and energy authority and secondarily commercial benefit. In the context of the eeefff train intervention, for instance, an infrastructural strike also asserts primary control by demonstrating the right to act against what you don’t agree with, in the sense that the act itself is much more important than who stands behind it. For the sake of an overview, though, let us list alternative options of the culprit:

– The Russians, who might have done it to prevent being punished for not fulfilling their contractual obligations of natural gas supply (as suggested by NATO).

– Some type of Russian-Ukrainian non-state actor that aims to drive a deeper wedge between Germany and Russian energy entanglement (according to Germany).

– Ukraine, to prevent the future functioning of the pipelines that famously circumvent their territory (according to the USA).

– The calculative Americans to prevent Germany from lifting sanctions and benefit from selling gas to chilly Europe (according to Seymour Hersh and Russia).7

As I research this question of who did it, I wonder why the urgency of its answer somehow fades. As an underground engineering interference, the unidentified offender is congratulated. We wouldn’t want the activists to be identified publicly and prosecuted, and anonymity is an asset and a triumph. On the other hand, and rightfully so, if perceived as a geopolitical maneuver and financially incentivized by the distributors of the ‘freedom gas’8, then the act has a terroristic tone and the previously unnamed perpetrator must be revealed and punished. It boils down to if you trust your source of information and its extent of access and sight.

Probably the Americans were behind it, but that’s beside the point. Knowing that optic and network technologies are the result of an ideological and technocratic race I am faced with the fact that I must choose which line of vision I want to align with, by navigating the intimate data sets discovered along the way.

—

More on Klara Debeljak here: https://www.instagram.com/klara.deb/.

FOOTNOTES

1. Quoted in Wolukau-Wanambwa S. (2021) Dark Mirrors, London: Mackbooks, p. 93.

2. See Borisionok A. (2022) Queer Temporalities and Protest Infrastructures in Belarus, 2020 – 22: A Brief Museum Guide, www.e-flux.com/journal/127/466031/queer-temporalities-and-protest-infrastructures-in-belarus-2020-22-a-brief-museum-guide/.

3. thezetkincollective.org. (n.d.) White Skin, Black Fuel: On The Danger Of Fossil Fascism, www.thezetkincollective.org.

4. Schneidler F, Seymour Hersh: The US Destroyed the Nord Stream Pipeline. In: Jacobin. www.jacobin.com/2023/02/seymour-hersh-interview-nord-stream-pipeline?fbclid=IwAR27AVGROeEuaO0vIQeFtAJH_PBYV_oPGnFv8Z2SPSpVIMp21X32J0dl9BA.

5. Wilkenfeld, Y. (2022) Europe and Russia without Nord Stream. GIS Reports, www.gisreportsonline.com/r/russia-without-nord-stream/.

6. Ambrose, J. and correspondent, J.A.E. (2023) Exxon CEO’s pay rose 52% to nearly £30m amid Ukraine war, figures show, In: The Guardian, April 13, 2023, www.theguardian.com/business/2023/apr/13/exxon-ceo-darren-woods-pay-rise-ukraine-war-oil.

7. Danner, C. (2023). Who Blew Up the Nord Stream Pipeline? Intelligencer, www. nymag.com/intelligencer/2023/04/who-blew-up-the-nord-stream-pipeline-suspects-and-theories.html.

8. Radynski, O. (2020) Is Data the New Gas? – Journal #107, in: e-flux, www.e-flux.com/journal/107/322782/is-data-the-new-gas/.

INC stands in solidarity with the Casual UvA protest: We Are Not Disposable

We publish here the press release of today's protest at the University of Amsterdam from the collective Casual UvA (Nederlandse versie hieronder).

We Are Not Disposable: ‘Wegwerpdocenten’ at the University of Amsterdam organizing a demonstration

On April 20, at 17:00, Casual UvA, a collective of university employees – the majority on temporary contracts and a few on permanent contracts who are sympathetic to the cause – organized a demonstration in front of the ABC building at the Roeterseiland Campus (REC) to protest the ongoing issue of casualization and the replacement of colleagues under the slogan “We are not disposable”. This is a response to the ongoing casualization, which is the altering of working practices so that regular workers are re-employed on a short-term basis.

In April 2022, UvA lecturers went on a marking strike asking for permanent contracts, professional development and workload transparency. On June 7th, the marking strike was suspended with the negotiation of a new lecturer policy, with the promise of a transparent implementation and an open conversation regarding the casualization of academia.

One year later, junior lecturers in precarious, temporary contracts are still being de facto fired and continuously replaced. The lack of concrete solutions and transparent implementation of the new lecturer policy does not do justice to the severity of the conditions and the challenges that junior temporary lecturers are facing. Casual UvA highlights the issue of unofficially denying permanent contracts to employees without a PhD degree, leading to arbitrary replacement of colleagues who successfully, and passionately performed structural work.

This continuous cycle of replacing lecturers on temporary contracts every 3-4 years with new and less experienced lecturers does not only undermine labor rights for lecturers, but also disregards the quality of education for students. Temporary contracts are not meant for continuous, structural teaching jobs that are needed every year. The university does not only dispose of the teaching experience that the lecturer has gained, it also destroys social consistency and opportunities for continued collaboration between teachers, as well as students and teachers.

Sam Hamer, junior lecturer in Sociology: “while we had hoped for improved working conditions in the aftermath of the grading strike of 2022, we find ourselves in the same situation as last year. Soon, again, we will have to say goodbye to many of our colleagues because they have to shoulder the UvA’s precarity.”

Additionally, Casual UvA are calling for a re-calculation of hours and sufficient time for teaching tasks across all faculties to address structural overwork and the lack of professional development opportunities for junior colleagues, who are being treated by the university as disposable employees, ultimately decreasing the quality of education.

————-

Wegwerpdocenten aan de UvA organiseren demonstratie: ‘We Are Not Disposable’

Op 20 april om 17:00 uur georganiseerd Casual UvA een demonstratie om te protesteren tegen de aanhoudende kwestie van tijdelijke contracten (casualisering) en de voortdurende vervanging van collega’s onder de slogan We Are Not Disposable (“Wij zijn niet wegwerpbaar”). De locatie van de demonstratie is vlak bij het ABC-gebouw op de Roeterseiland Campus (REC).

Casual UvA een collectief van universiteitsmedewerkers die voornamelijk op tijdelijk contract werken, met steun van een aantal collega’s op permanent contract. De demonstratie van 20 april is een reactie op de voortdurende casualisering, waarbij werknemers die structureel werk doen op korte termijn opnieuw worden aangenomen. Docenten worden dus als tijdelijke krachten behandeld en om de 3-4 jaar zonder pardon vervangen, terwijl zij structureel werk leveren waar ieder jaar vraag naar is.

In april 2022, ongeveer een jaar geleden, organiseerden UvA-docenten als Casual UvA een staking om permanente contracten, professionele ontwikkeling en transparantie van werkdruk te eisen. Op 7 juni werd de staking opgeschort na onderhandelingen over een nieuw docentenbeleid, met de belofte van een transparante uitvoering en een open gesprek over de casualisering van de academische wereld.

Een jaar later worden junior docenten met precaire, tijdelijke contracten nog steeds de facto ontslagen en voortdurend vervangen. Het gebrek aan concrete oplossingen en transparante uitvoering van het nieuwe docentenbeleid doet geen recht aan de ernst van de omstandigheden en uitdagingen waarmee junior docenten op tijdelijk contract worden geconfronteerd. Casual UvA benadrukt het probleem van het onofficieel ontzeggen van permanente contracten aan werknemers zonder PhD-titel, wat leidt tot willekeurige vervanging van collega’s die structureel werk succesvol en met veel passie hebben uitgevoerd.

Deze voortdurende cyclus van het vervangen van docenten op tijdelijke contracten met nieuwe en minder ervaren docenten ondermijnt niet alleen de arbeidsrechten van docenten, maar negeert ook de kwaliteit van het onderwijs voor studenten. Tijdelijke contracten zijn niet bedoeld voor continue, structurele onderwijstaken die elk jaar nodig zijn. De universiteit gooit niet alleen de onderwijservaring weg die de docent heeft opgedaan, maar doet ook afbreuk aan de sociale consistentie en mogelijkheden voor langdurige samenwerking tussen docenten en studenten.

Sam Hamer, juniordocent in Sociologie: “in de nasleep van de staking van 2022 hadden we gehoopt op betere arbeidsomstandigheden, maar we bevinden ons in dezelfde situatie als een

jaar geleden. Binnenkort moeten we weer afscheid nemen van veel van onze collega’s omdat zij de dupe worden van de precaire arbeidsomstandigheden aan de UvA.”

Daarnaast roept Casual UvA de universiteit op tot een herberekening van de uren en voldoende tijd voor onderwijstaken in alle faculteiten om structurele overbelasting en het gebrek aan professionele ontwikkelingsmogelijkheden voor junior-collega’s aan te pakken, die door de universiteit als wegwerpbare werknemers worden behandeld, wat uiteindelijk ook de studenten raakt: al deze factoren verminderen de kwaliteit van het onderwijs.

New INC Telegram Channel

We invite you to join our new Telegram channel, a place where we can connect through collaborative conversations, livestreams and the sharing of our latest publications such as books, zines, articles, videos, events and much more.

To subscribe to the Institute of Network Cultures channel click here:

In our Telegram channel, we encourage you to use the comment section to engage in critical conversation but lurking is also fully supported. Because we believe in self-organisation, comments will not be actively moderated. If you find yourself uncomfortable with any content or comment you can report it to us via info@networkcultures.org.

Let’s enjoy digital awkwardness together.

You can also subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with what we have been working on by clicking here:

OUT NOW – THE VOID | Video in an Envelope #1 – GIFTED

GIFTED

A documentary about Clarisse Catlynn

By Morgane Billuart

“Seeking to see beyond the limits of sight forces the gazer into realms of spirituality, areas where sociology fears to tread”

Visual Spirituality, Kirean Flanagn

—

THE VOID | A Video in an Envelope #1

Video in an Envelope is a series of zines by THE VOID, a research project at the Institute of Network Cultures. The aim is to experiment with expanded publishing for practice based research. Video in an Envelope is a series developed from the need to publish audiovisual projects through alternative distribution networks.

More Info HERE

Order a copy HERE

“Caught a Vibe”: TikTok and The Sonic Germ of Viral Success

“When I wake up, I can’t even stay up/I slept through the day, fuck/I’m not getting younger,” laments Willow Smith of The Anxiety on “Meet Me at Our Spot,” a track released through MSFTSMusic and Roc Nation in March of 2020. Despite the song’s nature as a “sludgy alternative track with emo undertones that hits at the zeitgeist,” “Meet Me at Our Spot” received very little attention after its initial release and did not chart until the summer of 2021, when it went viral on TikTok as part of a dance trend. The short-form video app which exploded in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic, catalyzed the track’s latent rise to success where it reached no. 21 on the US Billboard Hot 100, becoming Willow’s highest charting song since her 2010 hit, “Whip My Hair”.

The app currently known as TikTok began as Musical.ly, which was shuttered in 2017 and then rebranded in 2018. By March of 2021, the app boasted one billion worldwide monthly users, indicative of a growth rate of about 180%. This explosion was in many ways catalyzed by successive lockdowns during the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the relaxation and subsequent abandonment of COVID mitigation measures, the app has retained a large volume of its users, remaining one of the highest grossing apps in the iOS environment. TikTok’s viral success (both as noun and adjective) has worked to create a kind of vibe economy in which artists are now subject to producing a particular type of sound in order to be rendered legible to the pop charts.

For anyone who has yet to succumb to the TikTok trap, allow me to offer you a brief summary of how it functions. Upon opening it, you are instantly fed content. Devoid of any obvious internal operating logic, it is the media equivalent of drinking from a fire hose. Immersive and fast-paced, users vertically scroll through videos that take up their entire screen. Within five minutes of swiping, you can–if your algorithm is anything like mine–see: cute pet videos, protests against police brutality, HypeHouse dance trends, thirst traps, contemporary music, therapy tips, attractive men chopping wood, attractive women lifting weights, and anything else you can fathom. Since its shift from Musical.ly, the app has also been a staging ground for popular music hits such as Lil Nas X’s’ “Old Town Road”, Lizzo’s “Good As Hell”, and, recently, Harry Styles’ “As It Was.”

The app, which is the perfect–if chaotic–fusion of both radio and video is enmeshed in a wider media ecosystem where social networking and platform capitalism converge, and as a result, it seems that TikTok is changing the music industry in at least three distinct ways:

First, it affects our music consumption habits. After hearing a snippet of a song used for a TikTok, users are more likely to queue it up on their streaming platform of choice for another, more complete listen. Unlike those platforms, where algorithms work to feed a listener more of what they’ve already heard, TikTok feeds a listener new content. As a result, there’s no definitive likelihood that you’ve previously heard the track being used as a sound. Therefore, TikTok works the way that Spotify used to: as a mechanism for discovery.

Second, TikTok is changing the nature of the single. Rather than relying upon a label as the engine behind a song’s success, TikTok disseminates tracks–or sounds as they’re referred to in the app–widely, determining a song’s success or role as a debut within a series of clicks. Particularly during the pandemic, when musicians were unable to tour, TikTok’s relationship to the industry became even more salient. Artists sought new ways to share and promote their music, taking to TikTok to release singles, livestream concerts, and engage with fans. Moreover, Spotify’s increasingly capacious playlist archive began to boast a variety of tracklists with titles such as, “Best TikTok Songs 2019-2022”, “TikTok Songs You Can’t Get Out Of Your Head”, and “TikTok Songs that Are Actually Good” among others. The creation and maintenance of this feedback loop between TikTok and Spotify demonstrates not only the centrality of social media ecosystems as driving current popular music success, but also the way that these technologies work in harmony to promote, sustain, or suppress interest in a particular tune.

Most notoriously, the bridge of Olivia Rodrigo’s “drivers license”, went viral as a sound on TikTok in January 2021 and subsequently almost broke the internet. Critics have praised this 24-second section as the highlight of the song, underscoring Rodrigo’s pleading soprano vocals layered over moody, syncopated digital drums. Shortly after it was released, the song shattered Spotify’s record for single-day streams for a non-holiday song. New York Times writer Joe Coscarelli notes of Rodrigo’s success, “TikTok videos led to social media posts, which led to streams, which led to news articles , and back around again, generating an unbeatable feedback loop.”

And third, where songwriting was once oriented towards the creation of a narrative, TikTok’s influence has led artists to a songwriting practice that centers on producing a mood. For The New Yorker, Kyle Chayka argues that vibes are “a rebuke to the truism that people want narratives,” suggesting that the era of the vibe indicates a shift in online culture. He argues that what brings people online is the search for “moments of audiovisual eloquence,” not narrative. Thus, on the one hand, media have become more immersive in order to take us out of our daily preoccupations. On the other, media have taken on a distinct shape so that they can be engaged while doing something else. In other words, media have adapted to an environment wherein the dominant mode of consumption is keyed toward distraction via atmosphere.

Despite their relatively recent resurgence in contemporary discourse, vibes have a rich conceptual history in the United States. Once a shorthand for “vibration” endemic to West Coast hippie vernacular, “vibes” have now come to mean almost anything. In his work on machine learning and the novel form, Peli Grietzer theorizes the vibe by drawing on musician Ezra Koenig’s early aughts blog, “Internet Vibes.” Koenig writes, “A vibe turns out to be something like “local colour,” with a historical dimension. What gives a vibe “authenticity” is its ability to evoke–using a small number of disparate elements–a certain time, place, and milieu, a certain nexus of historic, geographic, and cultural forces.” In his work for Real Life, software engineer Ludwig Yeetgenstein defines the vibe as “something that’s difficult to pin down precisely in words but that’s evoked by a loose collection of ideas, concepts, and things that can be identified by intuition rather than logic.” Where Mitch Thereiau argues that the vibe might just merely be a vocabulary tick of the present moment, Robin James suggests that vibes are not only here to stay, but have in fact been known by many other names before. Black diasporic cultures, in particular, have long believed sound and its “vibrations had the power to produce new possibilities of social attunement and new modes of living,” as Gayle Wald’s “Soul Vibrations: Black Music and Black Freedom in Sound and Space,” attests (674). We might then consider TikTok a key method of dissemination for a maximalist, digital variant of something like Martin Heidegger’s concept of mood (stimmung), or Karen Tongson’s “remote intimacy.” The vibe is both indeterminate and multiple, a status to be achieved and the mood that produces it; vibes seek to promote and diffuse feelings through time and space.

Much current discourse around vibes insists that they interfere with, or even discourage academic interpretation. While some people are able to experience and identify the vibe—perform a vibe check, if you will—vibes defy traditional forms of academic analysis. As Vanessa Valdés points out, “In a post-Enlightenment world that places emphasis on logic and reason, there exists a demand that everything be explained, be made legible.” That the vibe works with a certain degree of strategic nebulousness might in fact be one of its greatest assets.

Vibes resist tidy classification and can thus be named across a variety of circumstances and conditions. Although we might think of the action of ‘vibing’ as embodied, and the term vibration quite literally refers to the physical properties of sound waves and their travel through various mediums, the vibe through which those actions are produced does not itself have to be material. Sometimes, they name a genre of feeling or energy: cursed vibes or cottagecore vibes. Sometimes, they function as a statement of identification: I vibe with that, or in the case of 2 Chainz’s 2016 hit, “it’s a vibe.” Sometimes, vibes are exchanged: you can give one, you can catch one, you can check one, So, while things like energy and mood—which are often taken as cognates for vibes—work to imagine, name, and evoke emotions, vibes are instead invitations.

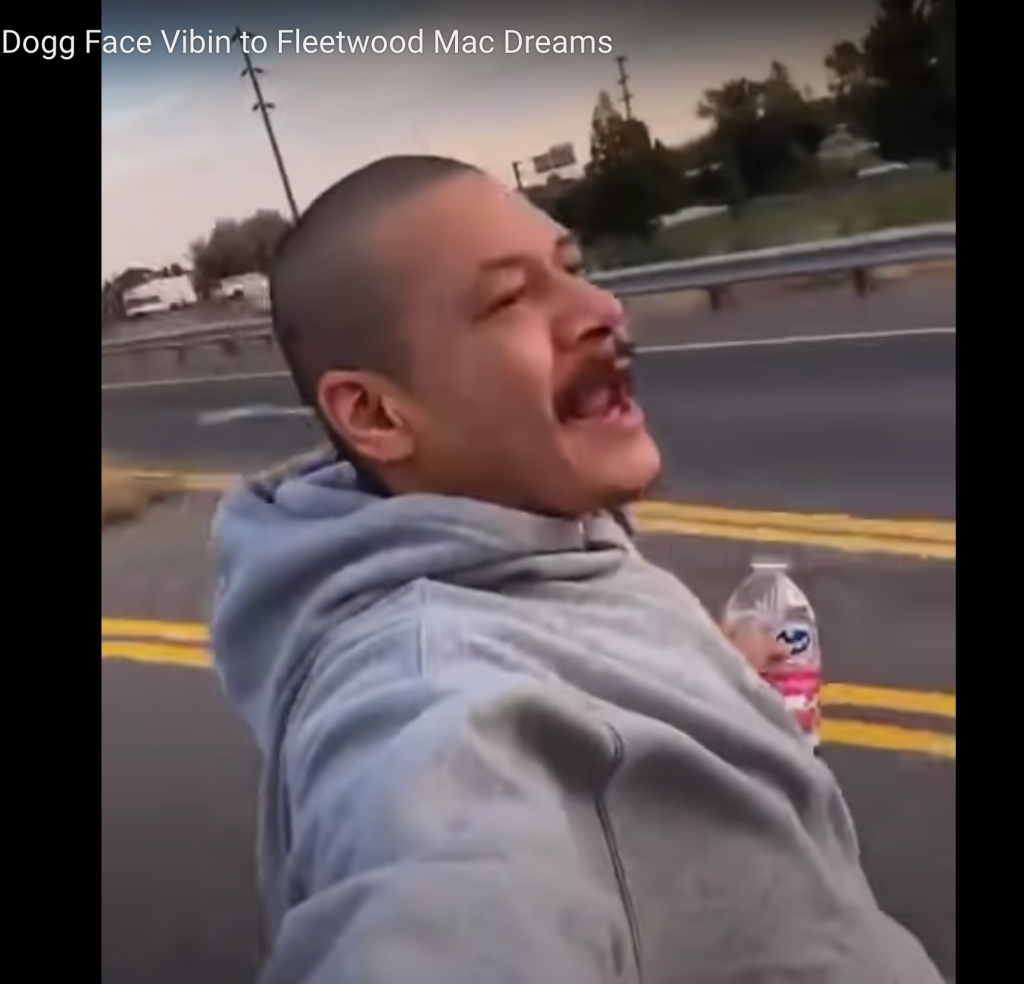

Not only do vibes serve as a prompt for an attempt at articulating experience, they are also invitations to co-presently experience what seems inarticulable. By capturing patterns in media and culture in order to produce a coherent image/sound assemblage, the production of a vibe is predicated upon the ability to draw upon large swathes of visual, aural, and environmental data. Take for example, the story of Nathan Apodaca, known by his TikTok handle as: 420doggface208. After posting a video of himself listening to Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams” while drinking cranberry juice and riding a longboard, Apodaca went viral, amassing something like 30 million views in mere hours. This subsequently sparked a trend in which TikTok users posted videos of themselves doing the same thing, using “Dreams” as the sound. According to Billboard, this sparked the largest ever streaming week for Fleetwood Mac’s 1977 hit with over 8.47 million streams. Of his overnight success, Apodaca says, “it’s just a video that everyone felt a vibe with.” To invoke a vibe is thus to make a particular atmosphere more comprehensible to someone else, producing a resonant effect that draws people together.

As both an extension and tool of culture, vibes are produced by and imbricated within broader social, political, and economic matrices. Recorded music has always been confined—for better and worse—to the technologies, formats, and mediums through which it has been produced for commercial sale. On a platform like TikTok, wherein the emphasis is on potentially quirky microsections of songs, artists are invited to key their work towards those parameters in order to maximize commercial success. Nowadays, pop songs are produced with an eye towards their ability to go viral, be remixed, re-released with a feature verse, meme’d, or included in a mashup. As such, when an artist ‘blows up’ on TikTok, it does not necessarily mean that the sound of the song is good (whatever that might mean). Rather, it might instead be the case that a hybrid assemblage of sound, performance, narrative, and image has coalesced successfully into an atmosphere or texture – that we recognize as a/the vibe – something that not only resonates but also sells well. As TikTok’s success continues to proliferate, the app is continually being developed in ways that make it an indispensable part of the popular music industry’s ecosystem. Whether by exposing users to new musical content through the circulation of sounds, or capitalizing upon the speed at which the app moves to brand a song a ‘single’ before it’s even released, TikTok leverages the vibe to get users to listen differently.

@jimmyfallon This one’s for you @420doggface208 #cranberrydreams#doggface208#dogfacechallenge♬ original sound – Jimmy Fallon

We might indeed consider vibes to be conceptual, affective algorithms created in the interstice between lived experience and new media. “Meet Me At Our Spot,” the track through which I’ve framed this article, is full of allusions to youth culture: drunk texts, anxiety over aging, and late-night drives on the 405. It is buoyed by a propulsive bass line that thumps with a restless energy and evokes a mood of escapism. Willow Smith’s intriguing timbre and the pleasing harmonies she achieves with Tyler Cole invite listeners to ride shotgun. For the two minutes and twenty-two seconds of the song, we are immersed within their world. In the final measures the pop of the snare recedes into the background and Tyler’s voice fades away. The vibe of the track – both sonically and thematically – is predicated on the experience of a few, fleeting moments. Willow leaves us with a final provocation, one that resonates with popular music’s current mode: “Caught a vibe, baby are you coming for the ride?”

—

Featured Image: Screencap of Nathan Apodaca’s viral TikTok post, courtesy of SO! eds.

—

Jay Jolles is a PhD candidate in American Studies at the College of William and Mary currently at work on a dissertation tentatively titled “Man, Music, and Machine: Audio Culture in a/the Digital Age.” He is an interdisciplinary scholar with interests in a wide range of fields including 20th and 21st century literature and culture, critical theory, comparative media studies, and musicology. Jay’s scholarly work has appeared in or is forthcoming from The Los Angeles Review of Books, U.S. Studies Online, and Comparative American Studies. His essays can be found in Per Contra, The Atticus Review, and Pidgeonholes, among others. Prior to his time at William and Mary, he was an adjunct professor of English at Drexel University and Rutgers University-Camden.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Listen to yourself!: Spotify, Ancestry DNA, and the Fortunes of Race Science in the Twenty-First Century”–Alexander W. Cohen

Evoking the Object: Physicality in the Digital Age of Music–-Primus Luta

“Music is not Bread: A Comment on the Economics of Podcasting”-Andreas Duus Pape

“Pushing Record: Labors of Love, and the iTunes Playlist”–Aaron Trammell

Critical bandwidths: hearing #metoo and the construction of a listening public on the web–Milena Droumeva

TiK ToK: Post-Crash Party Pop, Compulsory Presentism and the 2008 Financial Collapse—Dan DiPiero (The other “TikTok”! The people need to know!)

“Caught a Vibe”: TikTok and The Sonic Germ of Viral Success

“When I wake up, I can’t even stay up/I slept through the day, fuck/I’m not getting younger,” laments Willow Smith of The Anxiety on “Meet Me at Our Spot,” a track released through MSFTSMusic and Roc Nation in March of 2020. Despite the song’s nature as a “sludgy alternative track with emo undertones that hits at the zeitgeist,” “Meet Me at Our Spot” received very little attention after its initial release and did not chart until the summer of 2021, when it went viral on TikTok as part of a dance trend. The short-form video app which exploded in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic, catalyzed the track’s latent rise to success where it reached no. 21 on the US Billboard Hot 100, becoming Willow’s highest charting song since her 2010 hit, “Whip My Hair”.

The app currently known as TikTok began as Musical.ly, which was shuttered in 2017 and then rebranded in 2018. By March of 2021, the app boasted one billion worldwide monthly users, indicative of a growth rate of about 180%. This explosion was in many ways catalyzed by successive lockdowns during the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the relaxation and subsequent abandonment of COVID mitigation measures, the app has retained a large volume of its users, remaining one of the highest grossing apps in the iOS environment. TikTok’s viral success (both as noun and adjective) has worked to create a kind of vibe economy in which artists are now subject to producing a particular type of sound in order to be rendered legible to the pop charts.

For anyone who has yet to succumb to the TikTok trap, allow me to offer you a brief summary of how it functions. Upon opening it, you are instantly fed content. Devoid of any obvious internal operating logic, it is the media equivalent of drinking from a fire hose. Immersive and fast-paced, users vertically scroll through videos that take up their entire screen. Within five minutes of swiping, you can–if your algorithm is anything like mine–see: cute pet videos, protests against police brutality, HypeHouse dance trends, thirst traps, contemporary music, therapy tips, attractive men chopping wood, attractive women lifting weights, and anything else you can fathom. Since its shift from Musical.ly, the app has also been a staging ground for popular music hits such as Lil Nas X’s’ “Old Town Road”, Lizzo’s “Good As Hell”, and, recently, Harry Styles’ “As It Was.”

The app, which is the perfect–if chaotic–fusion of both radio and video is enmeshed in a wider media ecosystem where social networking and platform capitalism converge, and as a result, it seems that TikTok is changing the music industry in at least three distinct ways:

First, it affects our music consumption habits. After hearing a snippet of a song used for a TikTok, users are more likely to queue it up on their streaming platform of choice for another, more complete listen. Unlike those platforms, where algorithms work to feed a listener more of what they’ve already heard, TikTok feeds a listener new content. As a result, there’s no definitive likelihood that you’ve previously heard the track being used as a sound. Therefore, TikTok works the way that Spotify used to: as a mechanism for discovery.

Second, TikTok is changing the nature of the single. Rather than relying upon a label as the engine behind a song’s success, TikTok disseminates tracks–or sounds as they’re referred to in the app–widely, determining a song’s success or role as a debut within a series of clicks. Particularly during the pandemic, when musicians were unable to tour, TikTok’s relationship to the industry became even more salient. Artists sought new ways to share and promote their music, taking to TikTok to release singles, livestream concerts, and engage with fans. Moreover, Spotify’s increasingly capacious playlist archive began to boast a variety of tracklists with titles such as, “Best TikTok Songs 2019-2022”, “TikTok Songs You Can’t Get Out Of Your Head”, and “TikTok Songs that Are Actually Good” among others. The creation and maintenance of this feedback loop between TikTok and Spotify demonstrates not only the centrality of social media ecosystems as driving current popular music success, but also the way that these technologies work in harmony to promote, sustain, or suppress interest in a particular tune.

Most notoriously, the bridge of Olivia Rodrigo’s “drivers license”, went viral as a sound on TikTok in January 2021 and subsequently almost broke the internet. Critics have praised this 24-second section as the highlight of the song, underscoring Rodrigo’s pleading soprano vocals layered over moody, syncopated digital drums. Shortly after it was released, the song shattered Spotify’s record for single-day streams for a non-holiday song. New York Times writer Joe Coscarelli notes of Rodrigo’s success, “TikTok videos led to social media posts, which led to streams, which led to news articles , and back around again, generating an unbeatable feedback loop.”

And third, where songwriting was once oriented towards the creation of a narrative, TikTok’s influence has led artists to a songwriting practice that centers on producing a mood. For The New Yorker, Kyle Chayka argues that vibes are “a rebuke to the truism that people want narratives,” suggesting that the era of the vibe indicates a shift in online culture. He argues that what brings people online is the search for “moments of audiovisual eloquence,” not narrative. Thus, on the one hand, media have become more immersive in order to take us out of our daily preoccupations. On the other, media have taken on a distinct shape so that they can be engaged while doing something else. In other words, media have adapted to an environment wherein the dominant mode of consumption is keyed toward distraction via atmosphere.

Despite their relatively recent resurgence in contemporary discourse, vibes have a rich conceptual history in the United States. Once a shorthand for “vibration” endemic to West Coast hippie vernacular, “vibes” have now come to mean almost anything. In his work on machine learning and the novel form, Peli Grietzer theorizes the vibe by drawing on musician Ezra Koenig’s early aughts blog, “Internet Vibes.” Koenig writes, “A vibe turns out to be something like “local colour,” with a historical dimension. What gives a vibe “authenticity” is its ability to evoke–using a small number of disparate elements–a certain time, place, and milieu, a certain nexus of historic, geographic, and cultural forces.” In his work for Real Life, software engineer Ludwig Yeetgenstein defines the vibe as “something that’s difficult to pin down precisely in words but that’s evoked by a loose collection of ideas, concepts, and things that can be identified by intuition rather than logic.” Where Mitch Thereiau argues that the vibe might just merely be a vocabulary tick of the present moment, Robin James suggests that vibes are not only here to stay, but have in fact been known by many other names before. Black diasporic cultures, in particular, have long believed sound and its “vibrations had the power to produce new possibilities of social attunement and new modes of living,” as Gayle Wald’s “Soul Vibrations: Black Music and Black Freedom in Sound and Space,” attests (674). We might then consider TikTok a key method of dissemination for a maximalist, digital variant of something like Martin Heidegger’s concept of mood (stimmung), or Karen Tongson’s “remote intimacy.” The vibe is both indeterminate and multiple, a status to be achieved and the mood that produces it; vibes seek to promote and diffuse feelings through time and space.

Much current discourse around vibes insists that they interfere with, or even discourage academic interpretation. While some people are able to experience and identify the vibe—perform a vibe check, if you will—vibes defy traditional forms of academic analysis. As Vanessa Valdés points out, “In a post-Enlightenment world that places emphasis on logic and reason, there exists a demand that everything be explained, be made legible.” That the vibe works with a certain degree of strategic nebulousness might in fact be one of its greatest assets.

Vibes resist tidy classification and can thus be named across a variety of circumstances and conditions. Although we might think of the action of ‘vibing’ as embodied, and the term vibration quite literally refers to the physical properties of sound waves and their travel through various mediums, the vibe through which those actions are produced does not itself have to be material. Sometimes, they name a genre of feeling or energy: cursed vibes or cottagecore vibes. Sometimes, they function as a statement of identification: I vibe with that, or in the case of 2 Chainz’s 2016 hit, “it’s a vibe.” Sometimes, vibes are exchanged: you can give one, you can catch one, you can check one, So, while things like energy and mood—which are often taken as cognates for vibes—work to imagine, name, and evoke emotions, vibes are instead invitations.

Not only do vibes serve as a prompt for an attempt at articulating experience, they are also invitations to co-presently experience what seems inarticulable. By capturing patterns in media and culture in order to produce a coherent image/sound assemblage, the production of a vibe is predicated upon the ability to draw upon large swathes of visual, aural, and environmental data. Take for example, the story of Nathan Apodaca, known by his TikTok handle as: 420doggface208. After posting a video of himself listening to Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams” while drinking cranberry juice and riding a longboard, Apodaca went viral, amassing something like 30 million views in mere hours. This subsequently sparked a trend in which TikTok users posted videos of themselves doing the same thing, using “Dreams” as the sound. According to Billboard, this sparked the largest ever streaming week for Fleetwood Mac’s 1977 hit with over 8.47 million streams. Of his overnight success, Apodaca says, “it’s just a video that everyone felt a vibe with.” To invoke a vibe is thus to make a particular atmosphere more comprehensible to someone else, producing a resonant effect that draws people together.

As both an extension and tool of culture, vibes are produced by and imbricated within broader social, political, and economic matrices. Recorded music has always been confined—for better and worse—to the technologies, formats, and mediums through which it has been produced for commercial sale. On a platform like TikTok, wherein the emphasis is on potentially quirky microsections of songs, artists are invited to key their work towards those parameters in order to maximize commercial success. Nowadays, pop songs are produced with an eye towards their ability to go viral, be remixed, re-released with a feature verse, meme’d, or included in a mashup. As such, when an artist ‘blows up’ on TikTok, it does not necessarily mean that the sound of the song is good (whatever that might mean). Rather, it might instead be the case that a hybrid assemblage of sound, performance, narrative, and image has coalesced successfully into an atmosphere or texture – that we recognize as a/the vibe – something that not only resonates but also sells well. As TikTok’s success continues to proliferate, the app is continually being developed in ways that make it an indispensable part of the popular music industry’s ecosystem. Whether by exposing users to new musical content through the circulation of sounds, or capitalizing upon the speed at which the app moves to brand a song a ‘single’ before it’s even released, TikTok leverages the vibe to get users to listen differently.

@jimmyfallon This one’s for you @420doggface208 #cranberrydreams#doggface208#dogfacechallenge♬ original sound – Jimmy Fallon

We might indeed consider vibes to be conceptual, affective algorithms created in the interstice between lived experience and new media. “Meet Me At Our Spot,” the track through which I’ve framed this article, is full of allusions to youth culture: drunk texts, anxiety over aging, and late-night drives on the 405. It is buoyed by a propulsive bass line that thumps with a restless energy and evokes a mood of escapism. Willow Smith’s intriguing timbre and the pleasing harmonies she achieves with Tyler Cole invite listeners to ride shotgun. For the two minutes and twenty-two seconds of the song, we are immersed within their world. In the final measures the pop of the snare recedes into the background and Tyler’s voice fades away. The vibe of the track – both sonically and thematically – is predicated on the experience of a few, fleeting moments. Willow leaves us with a final provocation, one that resonates with popular music’s current mode: “Caught a vibe, baby are you coming for the ride?”

—

Featured Image: Screencap of Nathan Apodaca’s viral TikTok post, courtesy of SO! eds.

—

Jay Jolles is a PhD candidate in American Studies at the College of William and Mary currently at work on a dissertation tentatively titled “Man, Music, and Machine: Audio Culture in a/the Digital Age.” He is an interdisciplinary scholar with interests in a wide range of fields including 20th and 21st century literature and culture, critical theory, comparative media studies, and musicology. Jay’s scholarly work has appeared in or is forthcoming from The Los Angeles Review of Books, U.S. Studies Online, and Comparative American Studies. His essays can be found in Per Contra, The Atticus Review, and Pidgeonholes, among others. Prior to his time at William and Mary, he was an adjunct professor of English at Drexel University and Rutgers University-Camden.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Listen to yourself!: Spotify, Ancestry DNA, and the Fortunes of Race Science in the Twenty-First Century”–Alexander W. Cohen

Evoking the Object: Physicality in the Digital Age of Music–-Primus Luta

“Music is not Bread: A Comment on the Economics of Podcasting”-Andreas Duus Pape

“Pushing Record: Labors of Love, and the iTunes Playlist”–Aaron Trammell

Critical bandwidths: hearing #metoo and the construction of a listening public on the web–Milena Droumeva

TiK ToK: Post-Crash Party Pop, Compulsory Presentism and the 2008 Financial Collapse—Dan DiPiero (The other “TikTok”! The people need to know!)

Vivre au Nord-Cameroun. Enjeux, défis et stratégies

Sous la direction de Mouadjamou Ahmadou, Bjørn Arntsen et Warayanssa Mawoune

Sous la direction de Mouadjamou Ahmadou, Bjørn Arntsen et Warayanssa Mawoune

Pour accéder au livre en version html, cliquez ici.

Pour télécharger le PDF, cliquez ici.

Traversé par des crises sécuritaires, sanitaires, sociopolitiques et culturelles, le Nord-Cameroun fait face aujourd’hui à des défis multiformes. Dans une perspective pluri- et transdisciplinaire adossée sur du matériau visuel et des données empiriques, cet ouvrage collectif aborde des problématiques anthropologiques d’actualité liées au système de fonctionnement, d’organisation et de gestion de sociétés qui sont à cheval entre le traditionnel et la modernité. Les différentes contributions analysent en particulier les questions de conflits intercommunautaires et transfrontaliers, de migration dans les zones bordant le lac Tchad, les stratégies de résilience socioéconomique et culturelle des populations locales soumises à un système d’organisation sociétal ébranlé par les nombreuses crises ayant traversé la zone ces trois dernières décennies.

ISBN pour l’impression : 978-2-925128-23-6

ISBN pour le PDF : 978-2-925128-24-3

DOI : 10.5281/zenodo.8140114

329 pages

Design de la couverture : Kate McDonnell, photographie de Mouadjamou Ahmadou

Date de publication : avril 2023

***

I. Migration et insécurité

Bjørn Arntsen

Henri Mbarkoutou Mahamat

Robi Layio

II. Dynamiques sociales et résilience

Juvintus Guimaye

Élie Wouleo Kazla

Mouadjamou Ahmadou

Rachel Asta Méré

Gilbert Willy Tio Babena

Hamidou

III. Santé, économie et développement local

André Ganava

Warayanssa Mawoune

Robert Nanche Billa and Maidjonle Muruele Brillant

Tchoupno Ndjidda

Ibrahim Bienvenu Mouliom Moungbakou

Hamadama Aboubakar

Présentation de l’équipe éditoriale

À propos des Éditions science et bien commun