Facets

J.T. Leroy and Exploitative Transformations

Book Review

The Disobedient PLR

The Gift of Dr Michael Noble

Editorial

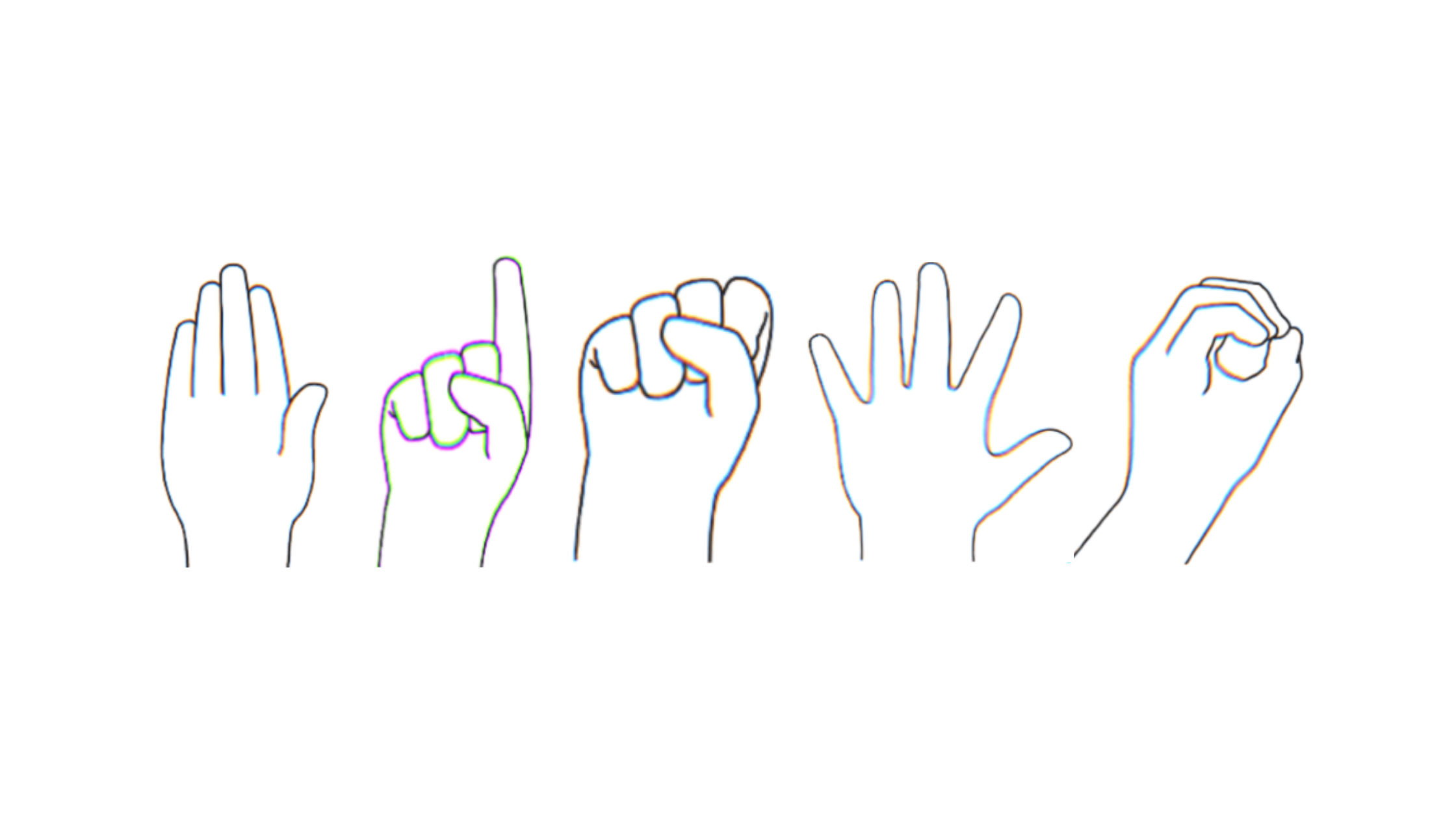

Tackling Simplified Sign System Handshapes: Five Basics to Get You Started

by Tracy T. Dooley

Signing can seem like a daunting task for hearing people who have never before tried to communicate using a sign language. The full and genuine sign languages of Deaf persons that are used around the world have their own distinct handshapes, vocabularies, grammars, and rules for usage within their societies. Studying one or more of the natural sign languages of Deaf persons can provide a fascinating look into the many fruitful and creative means of expression used by people from diverse sociocultural perspectives and life experiences.

My academic mentor, colleague, and beloved friend, John Bonvillian, spent his life dedicated to learning more about the sign languages of Deaf people and the ways in which manually produced signs could benefit the many individuals who struggle to communicate verbally and/or exist within a world dominated by speech. When John heard Gail Mayfield’s heartfelt entreaty to create a sign-communication system comprised of signs that would be easier to learn and form, he enthusiastically dedicated himself to that task with a joyful heart (see his brother William’s blogpost on The Possibility of Signs).

John’s linguistic research with Ted Siedlecki, Jr. in the 1990s regarding the formational parameters of American Sign Language (ASL) signs and how they are learned by the typically developing hearing and deaf children of Deaf parents (see Simplified Signs, Volume 1, Chapter 3) provided a sound foundation for the development of a sign system comprised mostly of easier-to-form handshapes. Their analysis found that forming correct handshapes was the most difficult task for young signing children to master. This was because the children’s ability to produce the more complex handshapes often present in Deaf sign languages frequently lagged behind the children’s ability to control the fine motor skills of their hands necessary to produce such complex handshapes.

Since many non-speaking or minimally verbal individuals may also have difficulties with fine motor control, particularly with the oromotor skills necessary for fluent speech and the manual motor skills necessary to produce recognizable signs, it is vital that signs used by such persons be relatively easy to form. In addition to noting the specific ASL handshapes that were more difficult to form by young signing children, Bonvillian and Siedlecki’s investigations found that certain handshapes were produced easily and accurately from a relatively young age. These handshapes included such basic handshapes as the flat-hand, the pointing-hand, the fist, and the spread- or 5-hand.

Not surprisingly, then, a preliminary analysis that I performed in 2015 of the handshapes used in the Simplified Sign System (SSS) showed that these four handshapes, along with the tapered- or O-hand, were the most prevalent handshapes in the first 1000 signs of the system. The flat-hand alone accounts for nearly 26% of the handshape usage. The pointing-hand, fist, and spread- or 5-hand account for roughly another 38.5%, and the tapered- or O-hand for 6.50%. These five handshapes together make up nearly 71% of all of the handshape usage in the initial lexicon. Thus, the majority of the signs available in Simplified Signs, Volume 2, Chapter 11 should be highly accessible to persons experiencing temporary or chronic difficulties with their motor skills.

In keeping with the ethos of universal design (see Simplified Signs, Volume 1, Preface and Acknowledgments), in which the development of a product, service, or environment takes into account the needs of people with a range of abilities, the Simplified Sign System should also be easy to use not only by non-speaking persons with motor impairments, but also by their family members, friends, work colleagues, and people in their communities. Indeed, we all benefit from such things as elevators, ramps, and other modifications to our environments, even if we forget the origins of these inventions in civil rights movements. In fact, one can argue that it is the presence of persons with various abilities and disabilities that helps to drive innovation, technological advancement, and positive societal changes that benefit everyone.

Plus, signing is not as daunting a task as you might think. In fact, accompanying our speech with manual gestures, facial expressions, and other bodily movements is something that many people do on a regular basis. Furthermore, such incorporation of communicative gestures with speech may be so prevalent that we do it without even thinking about it or being consciously aware of it. Try this fun experiment with someone you know and trust: when in the middle of a typical conversation with that person, stop moving your body, your arms, your hands, and your head. Also, stop using facial expressions—no eyebrow raises, no pursed lips, no smiles, no frowns, no rolls of the eyes, no gazing at anything or anyone except the person with whom you’re talking—and see how long you can keep it up. If the two of you aren’t laughing within minutes (or even seconds) of the switch, then you have truly overlooked the many ways in which our bodies and the parts of our bodies speak for us. Indeed, it can be extremely difficult to NOT use some form of communicative gesturing when speaking with others, especially with people you do not know.

As a result, many of you out there already have the basics of gestural communication in your skill set, even if you’re not consciously aware of it. So, do yourself a favor—let go of your fears, flex your fingers, and try to produce the following five most frequently used handshapes in the Simplified Sign System. If you don’t do it “right” the first time, try again! There’s no judgment here and no deadlines to meet. There is, however, quite a bit of room for laughter, fun, and the joy and satisfaction that come from learning to communicate with your hands.

Illustrations by Val Nelson-Metlay.

This book is now available to read and download for free. Please, click here to access Vol. 1 and here for Vol.2.

We will be hosting an Online Book Launch for this title on the 3rd September 2020 at 4 p.m. BST/ 11 a.m. EST. You can RSVP here.

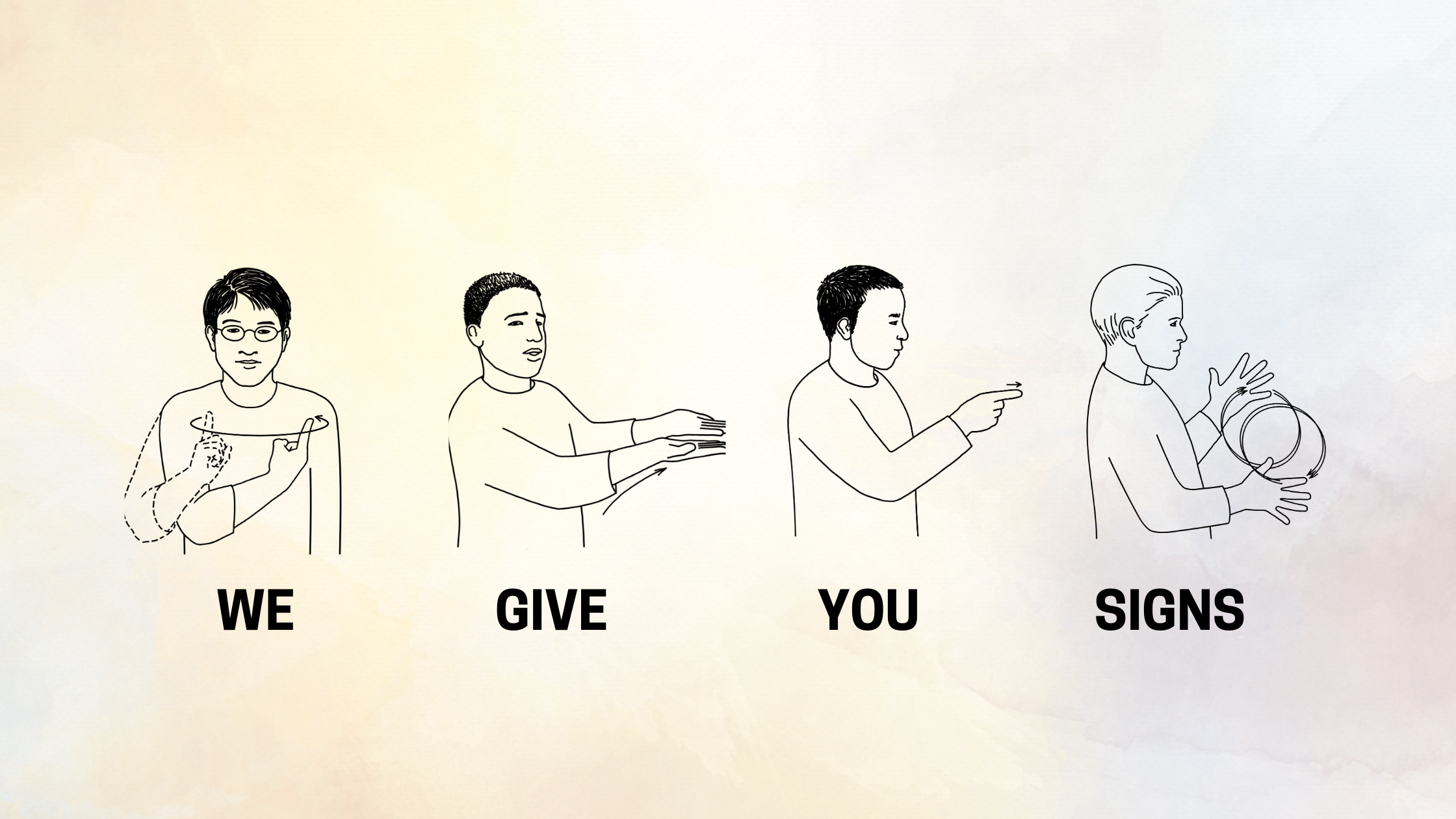

The Possibility of Signs

by William B. Bonvillian

Would it be possible?

With this question, Gail Mayfield, the director of an autism program in rural Virginia, inspired a project that would absorb the talents and passions of a virtual army of students and some faculty at the University of Virginia for over two decades. The project, called Simplified Signs, created an easy-to-learn sign-communication system that could “quite possibly” change the lives of the millions of people who face challenges with spoken communication, as well as their parents, teachers, caregivers, and friends.

In the late 1980’s, when Gail Mayfield first posed her question, some of the best special education programs in the United States for non-speaking children with autism used and taught American Sign Language (ASL) for communication. The late John Bonvillian was a professor of Psychology and Linguistics at the University of Virginia doing research on the use of signs by some of Mayfield’s students. Bonvillian had been at the forefront of a movement to use sign language in special education programs and his research with Mayfield’s students with autism was part of his ongoing professional interest in sign language usage.

Bonvillian heard Mayfield’s simple and well-placed query and took it to heart. Her students could learn and benefit from the use of signs, but they often had difficulty with some of the ASL handshapes, and their communicative progress was limited. Mayfield felt that her students would be able to communicate more fluently if they had signs that were easier to form and to remember. Would it be possible to develop such signs?

Bonvillian was, by nature, a careful academic, so he approached the question first by investigating the sign language acquisition of the typically developing children of Deaf parents. He then could compare those findings against the signing difficulties encountered by Mayfield’s students and by other persons with motor and memory problems. He found that such individuals often struggled with certain hand formations and with signs that required multiple movements. He also found that many parents and caregivers had not become fluent signers themselves; as a result, the students did not experience the substantial benefit of living in an environment where signs were used and understood by everyone.

Working with a talented undergraduate student named Nicole Kissane, who later became one of his three coauthors, Bonvillian conceived of the Simplified Sign System project. Together, Bonvillian and his research group took the first step toward the possibility of easier signs. The project goals were to identify a modest working vocabulary of signs that were 1) easy to form because they did not include complex handshapes or movements and 2) easy to remember because they looked like what they represented (that is, they were iconic). Bonvillian and his team found many such signs in the dictionaries of Native American signs, previously developed sign systems, and the sign languages of Deaf persons. When they couldn’t find pre-existing signs that met their criteria, they created some signs on their own. They then tested each and every one of the potential signs on students at the University of Virginia to ensure that the signs met the project criteria for formation and recall. The resulting product, which has been more than twenty years in the making, is Simplified Signs: A Manual Sign-Communication System for Special Populations. It is a two-volume set consisting of a compendium of the research on signing (Volume 1) and a lexicon of signs (Volume 2).

Simplified Signs has proven that with dedication and persistence, what was once barely conceivable may indeed be possible. Literally hundreds of people have participated in making Simplified Signs possible. While John Bonvillian did not live to see the publication of his work, it survives as a living tribute to his talents, dedication, and generosity, as well as that of his coauthors and the many others who brought this project to completion. It is published through Open Book Publishers and available online free of charge so that everyone may have access to the signs and use them.

Today the answer to Mayfield’s question “Would it be possible?” is an unqualified yes. Simplified Signs are not only possible; they are here.

Let’s use some now!

Written by William B. Bonvillian on behalf of his brother, John. Illustrations used on banner and body text by Val Nelson-Metlay.

Axel Andersson: To Inherit Thinking-Bernard Stiegler In Memoriam

We know how it sounds when the voice of those who are absent animate their words as we read them, as if from the inside of the text. How long after a disappearance is a voice activated through a postcard, a note on a piece of paper or a book? I reach for Bernard Stiegler’s books soon after receiving the news of his death in early August. There are many in my shelf, but far from all of the more than thirty that he wrote since the first volume of “La technique et le temps” in 1994. I read and I hear.

We are always out of step with ourselves. To be inscribed into life as an individual is to let oneself, perpetually, be shaped by other individuals and the traces of those that are no longer among us. It is only in death that we catch up. It is in death and in our transition to becoming traces that we reach pure presence, Stiegler writes. There ceases the eternal change.

It was through books, during a five-year long incarceration (1978-83) when the rest of the world was denied him, that Stiegler approached philosophy. He became fascinated with how the discipline through its history had been uninterested in technics. It was technics, encompassing everything from scripture to the production of books, that had made it possible for the traces of philosophy to reach all the way to him: a jazz-club owner and before that peasant who had, in one of the vicissitudes of life, started to rob banks and that now with the help of the philosopher Gérard Granel (previously a regular at Stiegler’s club) studied in his little cell.

It was Granel who pointed Stiegler on the way to Jacques Derrida. A philosopher whose engagement with language as technics had led him to formulate a way to show how also the text was out of step with itself. Stiegler came to study with Derrida as his supervisor. It was the beginning of a brilliant career as a philosopher and a public intellectual for the former convict. Early on he became interested by the new digital technologies and made himself into one of the thinkers who most systematically and persistently analysed and criticised the society that the digital and automatic was giving birth to.

By a culture scared to be questioned, Stiegler was often dismissed as a tiresome Cassandra entertaining a bestiary of hellish predictions. What he feared most of all was that the technological development had taken a tragic turn towards the nightmarish desert of the exhaustive calculation where nothing, not thought and not even dreams, would survive. A catastrophic automation captured by a suicidal capitalism destroying all the necessities of life. The collective knowledge of man had led to a technology that could be used to destroy all knowledge.

In the 2016 book “Dans la disruption” (with the telling subtitle: “how not to go mad?”) Stiegler recounts a scene from 1993. It is Sunday morning after a party that he has been to with his children Barbara and Julien, at the time twenty-three and nineteen. Barbara suddenly asks him why he always is so silent and sombre. He answers that they are now ready to be addressed as adults. He is sombre as prison has taught him the measure and price of things, but also because he has understood that the world was approaching what seemed like a trial that could lead to its dissolution. Yet he promises to never stop studying this trial, to keep on looking for a way in which the worse can be turned to something better and, all this failing, leave traces to inheritors resembling ourselves, with the testimony that there were those that fought and did all in their power to find a way forward.

We are, claimed Stiegler, beings whose need of external technical support is foundational for our existence. But every new technical development is both a poison and a cure, with other words a “pharmakon”. Living together with the necessary technics demands constant care transforming therapeutically that which poisons us, into something capable of curing. Care is knowledge, thinking, investment, something able to create the improbable, a generative madness that leads to new dreams. Knowledge is also the realization that something will also always escape our understanding. Without knowledge we become proletarians forced to adapt ourselves instead of being able to adopt a technical object and make it ours. We risk self-inflicting stupidity and scream for someone to blame (a scapegoat, a “pharmakos”, linked to “pharmakon”) to numb our pain.

His texts are often concerned with the distance between the “I” and the “we”. The two are eternally joined, but hopefully not synonymous. Predatory industrial extraction of our attention through the new digital technologies have for aim to eradicate this difference. It leads to a totalitarian system that reduces us (even our children, those who have not become adult and that we were there to protect) to interchangeable consumers. The development has perverted our infinite desire to finite drives and let short-sighted stupidity take the places of long-term knowledge. Political, media, economic and ecologic system have been undermined by our carelessness.

In 2003 the old left-wing sympathizer Stiegler dedicated a book to the voters or the xenophobic France party Front National. Not because he shared their opinions, far from it, but because he, despite that enormous political distance that was between them and him, felt near their pain. Individuals in a society that has lost faith in itself lack the primary narcissism and desire that facilitates the conversions of an “I” to a “we”. It is in desperation to reach this “we” that the scapegoat is created. It was this that the extreme right had done with the immigrant, and that Stiegler refused to do with the voters of the extreme right.

The path from the poisoned side of the technologized industrial society, that makes both poor and rich miserable, was for Stiegler not less technology. Such a retreat was impossible. He disliked all talk of “resistance”. We had to, though knowledge and care, instead invent new turns. It was a labour taking place in the attempts to create a “we”. For this end he sought to initiate dialogues and collaborations with other researchers than those in philosophy and with those outside of academia: politicians, religious leaders, artists, activists and industrialists – even with the digital enterprises that for short-term gain profited on the decomposition of the social. One large project that was launched in collaboration with a number of disadvantaged municipalities in the north of Paris 2016 had for aim to build a practical laboratory for new ways of living with today’s technology and to create a “contributive economy”.

It is desperately sad that Stiegler died as the world had taken a sharp turn towards the valley of the shadow of death with a depressing combination of climate crisis, pandemic and systemic loss of knowledge. We who feel the shame stand to inherit his thought, but how is thinking inherited? I read and with a sorrow inside I can hear him stress the word “nous” in French (we) and the almost homonymous “nous” (νοῦς), the classic Greek concept for intellect and reasons. How can we find the courage to think a future like ours?

Stiegler readily acknowledged the inheritance from Derrida (and the poisonous inheritance from Martin Heidegger), but clarified: to be faithful an inheritance means to criticize it, explore its boundaries and venture beyond. A trace has to lead to new bifurcations that puts us in front of the unknown. Knowledge cannot be preserved through repetition alone.

To die is to become a trace, something that contains both process and difference. Paradoxically, Stiegler also claimed that to die was to become a pure presence. Read through Derrida (who died in 2004, 74 years old, far too young like the now eternally 68-year old Stiegler) it is an enunciation hung over both sides of the scales of metaphysics. From the impossible perspective of the dead it is possible to be purely present, but then one can no longer exist. And the dead is unable to register how she is part of the constant developments between traces and fellow humans, even though she is still very much part. The thought as care must be extended to encompass and re-negotiate the “I”, the trace and the “we”, by the living through the dead.

Already in his first work Stiegler described the external (and therefor technical) memory as a process where lived history is “inscribed into death”. It lingers contrary to the “law of life”. Memory has, as he would later return to, therefore all the possibilities to continue life by other means than just life. A death that life needs to become new thoughts. Parts of the philosopher of techincs Stiegler, has now become technical objects himself. Even his equally warm as uncompromising voice, saved on thousands of recordings.

In 2009 Stiegler accepted to come and speak for a small and insignificant reading group that I organised together with Tania Espinoza at King’s College in Cambridge. In a somewhat confused time in my life he opened the door to a generous and intensively honest exchange that lasted up until, and beyond, his death. The history of the “I” is in its particulars rarely interesting, but because of its accidental nature there is sometimes no better illustration of the possible birth of the non-totalitarian “we” that Stiegler fought for. Contingency, as in personal meetings and singular circumstances, should not be reduced to “luck”. Through care we are capable of building conditions for that we cannot foresee. In the case of Stiegler, among other things a humane prison system (after his release partly destroyed) that allowed and facilitated his becoming a philosopher.

He who saves the life of one human, saves all of humanity. Thus it is written in both the Talmud and the Quran. As long as there is time, there is time for care. Towards the end Stiegler, himself without religious faith, affirmed that only a miracle could save us – often enunciated with the addition “God willing”: “Inshallah”.

Axel Andersson

(Swedish original published in Svenska Dagbladet 14 August 2020)