It is with joy that we present Let’s Get Physical: A Sample of INC Longforms, 2015-2020 (INC Reader #13), which gathers thirteen essays that have been published in our INC Longform series over the past years. The book is available for free as pdf and on paper, epub to follow soon. Below you can read the introduction to the volume. And do make sure to check INC Longforms for even more delicious reads.

—

What difference does five years make? A world of difference, no doubt about it. But, at the same time: ‘everything changes, and everything stays the same’.

What difference does five years make? A world of difference, no doubt about it. But, at the same time: ‘everything changes, and everything stays the same’.

I remember quite distinctly how, when I started working with the Institute of Network Cultures in 2012, many of the people around me had no idea of what we did and why. Why would you want to make a critique of Facebook (as we did in the Unlike Us project) when people enjoyed it so much? Why question the monopoly of Google on the search engine market (as Society of the Query did) when it so worked so well? Then Snowden happened, and while the implications of his revelations didn’t initially sink in with the broader public, they certainly did after Cambridge Analytica. The platforms that started out as your new best friend dirtied their reputations one after another and all by themselves: like the urban parasite Airbnb destroying livelihoods and communities, the all-encompassing warehouse of Amazon turning into a fresh-from-hell reinvention of the nineteenth century factory, or the complete and utter leeching of capital by Uber. Now, no one doubts whether the tech industry and Silicon Valley deserve scrutiny, even if billions still use their services.

A lot can happen over just a handful of years, while at the same time debates like these seemed to lay in waiting for ages, simmering in the back rooms of hacking clubs, art spaces, and academia. Still, there’s no saying where we’ll stand in another couple of years, or even the very near future. As I write this from home, confined to self-isolation, or quarantine, or whatever you wish to call it – just like a staggering number of people all over the world (and I’m very much aware that those who have the option to self-isolate in a home study, like me, are among the lucky ones) – it is hard not to look at the recent past with a kind of astonished bewilderment. Who could have figured that even the most dedicated tech critic would breathe a sigh of relief over the options offered by social networks and communication platforms to keep in touch with loved ones, co-workers, or even total strangers in a midnight rave via video conference? At the same time, it didn’t take long before the first worrying stories began to emerge about the use of the same tech to surveil citizens under lockdown in unprecedented ways and for workers in the platform economy to become more precarious than ever (if not ditched completely).

Longforms, a Short History

Amidst the rumbling, we find a reason to celebrate. This volume marks the five-year anniversary of the INC Longform series, which saw its first instalment in April 2015. Since then it has featured some thirty essays by smart, talented, often young writers. The topics they address range from emotion analysis through facial recognition technology to neo-cybernetic forms of (post)politics, among many others. Just like five or eight years ago there is criticism of tech monopolies, the notion of free labor, and the erosion of the social, but new issues are put on the agenda as well. Issues that we at INC think will gather increasing importance over the next five years, even if it’s impossible to look beyond a couple of months at the moment.

Before I go into these topics shortly, allow me to recount a short history of the INC Longform series. At the INC, publishing is a research topic in and of itself. The web for a large part may be considered a publishing medium (and revolution), so to approach the internet from a publishing perspective opens up many pathways for critical internet research, ranging from information politics, revenue models, and DIY practices, to cultural critique per se. Being an applied research center, we take pride in investigating the web-as-publication by publishing a range of works ourselves. And so, for the past decade and a half, we have grown into an experimental publisher of theory, toolkits, and anything else we think should enter the public domain.

The INC Longform series is no exception to the principle of research-by-doing. It all started with a collaboration with the Domain for Art Criticism and several cultural publications and platforms in the Netherlands and Flanders, who sought to (digitally) augment their practice as cultural critics. We tried our hands at podcasts, photo-essays, dialogic critique, collaborative writing, and, of course, longforms. In those days, ‘longform’ was no less than a buzzword – which is not meant to dismiss it, on the contrary. After years of suffering the torture of the bullet point article and the myth that no reading would ever take place online, the tide was turning. ‘Longread’ was no longer a dirty word, even if this concept has deteriorated over the past years to mean any piece of text that runs over a thousand words.

One of the most famous and referenced media productions of this period, at least among journalists and online writers, is without a doubt ‘Snow Fall,’ The New York Times 2012 epitome of multimedia longform production. While ‘Snow Fall’ set the standard for online longform publications, it was also almost impossible to achieve such standards for anyone for anyone else beyond a behemoth like The New York Times. You could say the contemporary history of longforms started at its peak and immediately descended from there. But this has only made it more interesting, opening up possibilities in many exciting directions. In our own DIY approach of the genre, we asked how we could put the technology to our own use, opening it up and making it available to those with tiny budgets and no helpdesk. The surge in longform writing moreover coincided with a revival of the essay, which has meant a great deal for more theoretical writing as well. Not shying away from the personal voice, juxtaposing examples from different sources, and allowing the reader to distill what is most important out of an open and searching narrative: these are traits that – luckily – have found their way into more academic styles.

The blending of online, multimodal, essayistic, and academic forms has been referred to as the blooming of the ‘para-academic’ by both Lauren Elkin and Marc Farrant in The Digital Critic. The para-academic is just as ambiguous and multi-faceted as it seems. It speaks to the general public, while also incorporating theory in sometimes quite weighty manners. It can follow a more artistic or literary approach, while making propositions or critique at the same time. It can comply with academic standards, while acknowledging the subjective and even personal. Often, concrete projects and personal experience, or practice-based, artistic, or applied research lies at its base. All essays in this collection relate to such a para-academic framework, which I consider as one of the most interesting recent developments in online writing and publishing practices. Of course, the rise of the para-academic (also) leads back to the precaritization of academia itself. It is within this context, too, that we hope to offer a place for writers to find an audience from all over the world, and to connect them through themes and times.

The INC longform series was thus set up with a focus on research content presented to a wider audience, designed for reading on the phone or tablet (remember those?), and would put text first, with other media playing a so-called ‘para-textual’ role. The (audio)visual material would complement the text and aid the reading experience but would not be necessary for appreciating the arguments made. There were several reasons for this delineation. Firstly, the written word was INC’s forte; secondly, we would not be able to make images, videos, or infographics especially for these publications, and would not be able nor willing to pay for expensive copyright; and thirdly, we would want the web pages to load easily for those with restricted bandwidth. With this in mind, you could say that we – per Hito Steyerl – enacted a ‘defense of the poor image’. It is a strategy that is pursued in this volume as well. Images may be a proven method to draw the reader in, but to do so they do not have to be flashy, High Design visuals. Au contraire, a vague, copied, meme-like reproduction can do the same.

If anything, the longform genre stirs up questions about the connections between the different types of media used. What is the function of images or other media in such a publication? What is this para-textual role that they play? What do they have to offer? There are many answers to those questions – pedagogically, images offer a different way of conveying information, esthetically, they make an article attractive. Within the context of reading on the web, which was so long deemed lost forever, you could also say that quite literally, an image offers distraction within an article. The web is the ultimate distraction machine, whether you believe in longreading online or not, and you cannot expect for a reader to pass undis- tracted through a couple thousands of words. So, you might as well offer modes of distraction yourself. The image allows for a pause and for a switch in ‘reading style’; looking at an image activates a different kind of attention, after which ideally the reading can resume afresh. This multimodality makes the longform format perfectly attuned to our times.

A Turn to the Physical

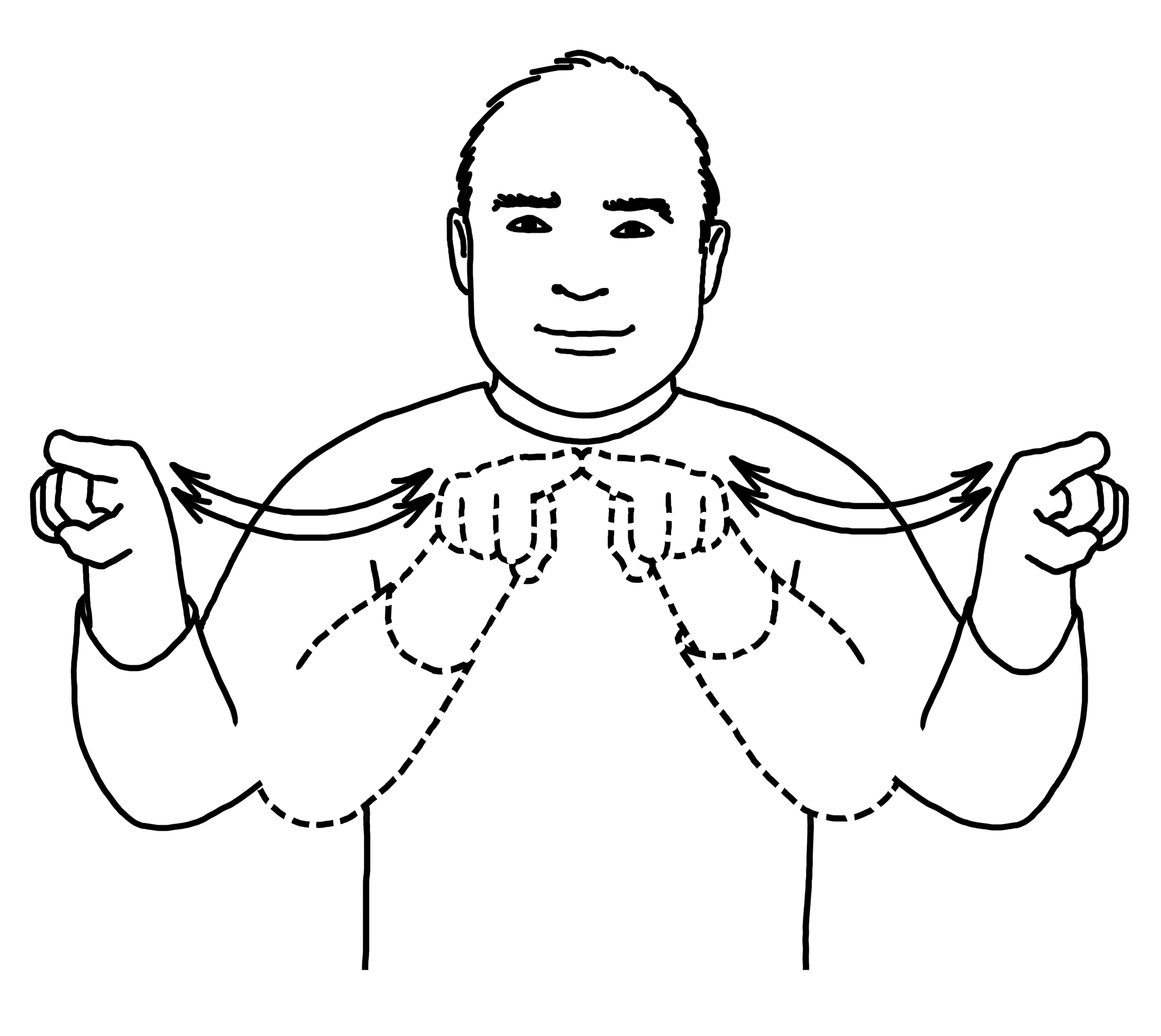

To close off, here is a short overview of what to expect. It wasn’t possible to collect all the longforms we’ve published over the years in one volume, and so this sample was guided by the question what topics we expect to grow on the agenda over the next five years. The title of the collection points to the overarching message: just like these longforms turn from pixels into paper, the internet itself physicalizes. Sure, the internet, media, and technology in general were never not physical to begin with, but it seems especially evident now that the post-digital age is characterized by a physical turn. This is not to reaffirm a dividing line between the virtual and physical. Rather, it is about their interaction – not just of humans with screens, but also of screens, algorithms, and other technologies with us and among each other as well, and within a shared environment that doesn’t care whether it’s called online or offline. The post-digital condition is first and foremost an entangled one.

This is undeniable in the first part titled ‘Affects & Interventions’, which puts forward the question of emotions, treats human-computer affection over interaction, and regards tangible and social relations in a world made up of post-human entities.

‘Class Lines’, the next section, investigates work and leisure. The analysis of users laboring for tech in a one-way street of exploitation is nuanced by sketching out the complexities of working in a thoroughly technological ecosystem, where the same tools are used for pleasure and for toil or could at least be appropriated as such. ‘Meme Politics’ then dives into the propelling of visual culture onto center stage of politics. Both the spread of extremist ideologies, communities that form around popular culture, and global politics are affected by the means of the meme. The final section ‘Architectures of Control’, looks into the physical interferences of technologies on the organization of information and people, and how they are used for control, oppression, and biopolitics. That may not be a happy note to conclude with, but it may serve as a reminder that while public discussion of big tech, social media, and platform capitalism has grown enormously over the past half-decade, the power of this same trio seems to have grown in parallel. If critique has become more mainstream, let’s make sure to keep it so.

A final thank you goes out to all the writers, editors, and collaborators on the series over the years, and most specifically to Leonieke, Jess, Matt, Inga, Isabella, Gráinne, and Silvio, who worked on the research back in the days, and to Elvira, Kirsten, Laura, and Barbara, for making this publication a physical reality.

Miriam Rasch, April 2020