WRITTEN BY: Hoçâ Cové-Mbede

The mandate of exclusive pay-wall access for scientific articles is nothing new inside research routines and academic cycles since the influx of virtual repositories in the 90’s information-rerun era [1], but the debates on whether or not these contents should become part of the public domain in contemporary network societies have arrived (alongside other rebukes on the copyright system) as controversial proxy discussions with Sci-Hub serving as the main emblem in anew digitally-grounded file-sharing culture.

Sci-Hub, a script that downloads HTML, PDF pages and journal articles directly from the publishers (similar to a web scraper) and hosted under nomad www.sci-hub domains due to constant blocking, was funded in September, 2011 by Alexandra Elbakyan, a neurotechnology researcher and self taught computer programmer with a major in Information Security based then in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Elbakyan ran Sci-Hub with a clever 3-day-in-the-making PHP code after facing frustrating reading fees from major publishers, which slowed the pace of her research tasks; that primal attempt proved to be successful, her science communication .net glitch quickly grew into a globalink phenomenon with persistent following and mass appeal that attracted mixed media treatments, critical engagement, academic support and legal trouble.

Rather than writing an extended essay about the events that defined Sci-Hub since its inception, here are nine public questions developed for Alexandra Elbakyan (open for feedback/response) that explore different subjects related with Sci-Hub’s timeline through 2011-2020 and go beyond the #RobinHood tag, the questions’ purpose and format is to expand the dialogues about the current status and future of this unprecedented project.

If access means power and power is fueled by elevated amounts of money, what are the standards of politically correct access to information aiming for, if not capital accumulation?

Questions

[1] I want to know your thoughts about the multiple profiles that depict you with specific word-associations and comparisons with other (Swartz / Piratebay / Napster / Megaupload / Wikileaks / Snowden / Manning, etc.) (punished) projects/public personas historically and culturally related with online piracy in USA. Even when you pointed out the problems of some of these profiles on your personal blog/s in the past, is crucial to address and insist about media development and treatment around your name in a wide spectrum in recent years, simply because that could trigger more attentive-branches about reductive misconceptions or elaborated images that some people may have about you.

I’ll take two cases as examples, a mainstream profile-feature published by The Verge in 2018 and an article from Nature in 2016 titled Paper piracy sparks online debate, both are highly cited/added in platforms and social media channels to identify and introduce people to your work, but at the same time both also developed specific agendas, avoiding open support (and probably legal threats or loss of sponsorship), is media output really engaging Sci-Hub’s aims and copyright enforcement accusations with the proper treatment?

[2] In the last three decades, ideas and activities associated with the word hacker were transformed radically, from being originally conceived in the background of programming-jargon, to get prosecuted with ‘illegal stickers’ ruled under the law, is a similar trend in which legal apparatuses label common words or compounds used in sharing networks and open knowledge activities as criminal-by-association in regards to free access and text-private-property. Conveniently, is an alarming reminding of the protective measures used in the Medieval Ages to prevent book-theft that you referenced in your text Анафема!, phantom-language for speculative punishment.

Why do you think these legal tactics under the argument of >capitalist loss< have been opportune to try to slow down sharing networks and archival repositories?

[2a] Do you consider these measures, like the legal prosecution directed by Elsevier to cease Sci-Hub in 2015, are similar reminiscences of Middle Age’s curses in the sense of status protection < via knowledge in XXIst century capitalism?

Here’s an extract of the actual complaint:

This is a civil action seeking damages and injunctive relief for: (1) copyright infringement under the copyright laws of the United States (17 U.S.C. § 101 et seq.); and (2) violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, 18.U.S.C. § 1030, based upon Defendants’ unlawful access to, use, reproduction, and distribution of Elsevier’s copyrighted works. Defendants’ actions in this regard have caused and continue to cause irreparable injury to Elsevier and its publishing partners (including scholarly societies) for which it publishes certain journals.

[3] Is fascinating how the tense relationship between USA and Russia during Cold War plays an important precedent in the public eye to generate plots and theories about the origins and intentions of Sci-Hub on copyrighted territories (even though you repeatedly insisted that Sci-Hub is a project you started in 2011), these theories suggest a plethoric range of prospects, from a fully state-funded project by Russian Intelligence, to an ongoing investigation directed by the US Justice Department that targets Sci-Hub as an undercover espionage-project.

What is your response to these accusations?

What is behind the constant emergence of conspiracy plots toward Sci-Hub?

[4] In 2016 Marcia Mcnutt (former president of the National Academy of Sciences) wrote a column for Science Magazine, My love-hate of Sci-Hub in which she argues that downloading papers from Sci-Hub could create collateral damage for authors, publishing houses, universities, fellowships, science education, among other areas. The love-hate scenario Mcnutt paints is nonetheless confusing for the debate she wants to open about corporate knowledge inside institutions, since, the whole text leaves serious cracks in her depiction of the publishing system’s function. Accidentally in the same text, she evidences a chain of normalized exploitation towards researchers in her community by not rewarding them in this excerpt:

“Journals have real costs, even though they don’t pay authors or reviewers, as they help ensure accuracy, consistency, and clarity in scientific communication.”

If access means power and power is fueled by elevated amounts of money, what are the standards of politically correct access to information aiming for, if not capital accumulation? Sci-Hub proposes a deep change into the file-share landscape.

[5] Sci-Hub’s bounder-less pirate distribution is generating not only scientific capital but also cultural capital, knowledge-availability never experienced before. Language barriers aside, the capacities for scientific development in countries with research shortages may have a significant growth in the next ten years thanks to Theft Trade Communication.

In a presentation you made this year about the mythology of science titled The Open Science Idea you showed an unexpected statement: modern science grew out of theft.

What is the nexus between cognition, communism, and theft inside your studies about the cultural history of science?

If Sci-Hub could release an official theft-ethos, what it would contain?

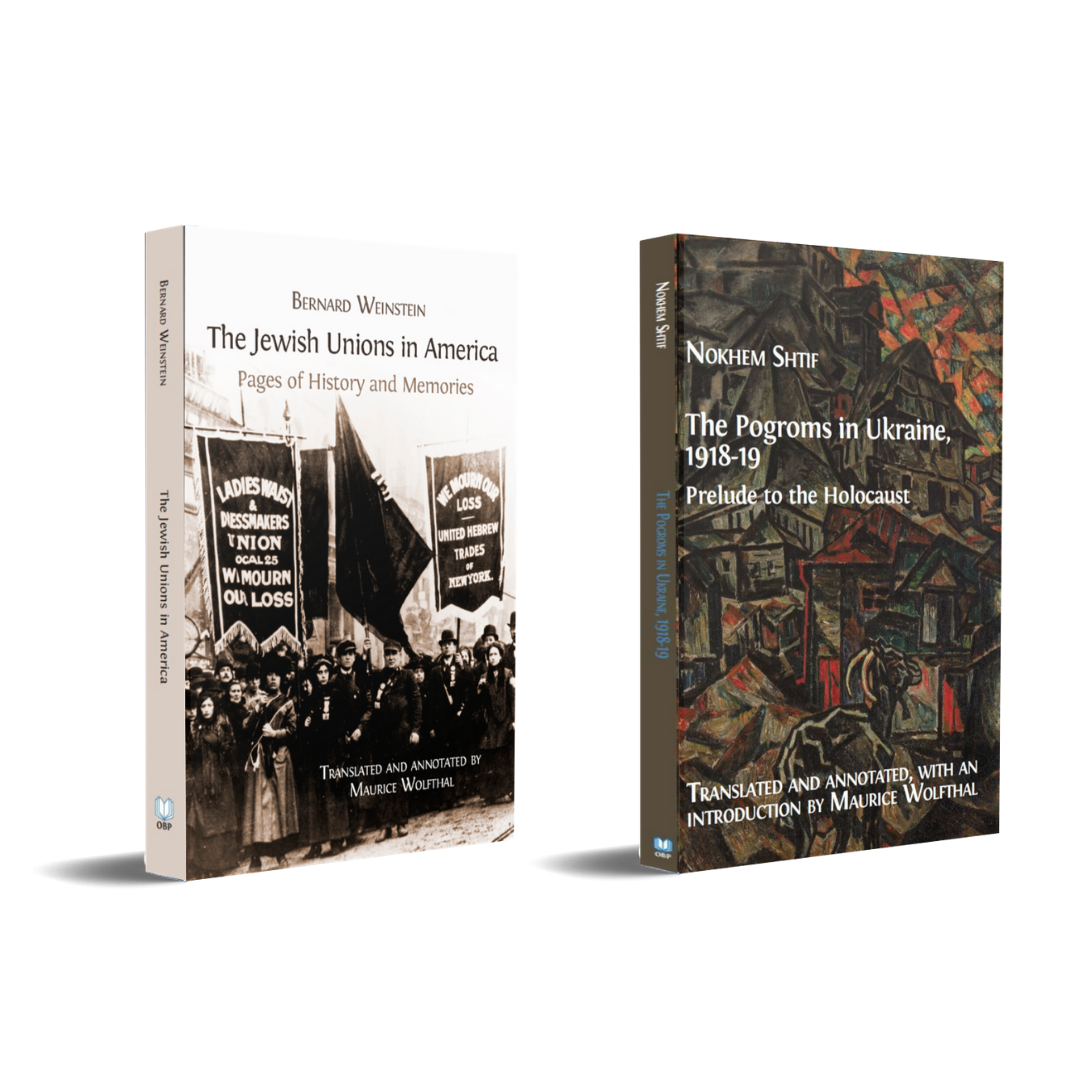

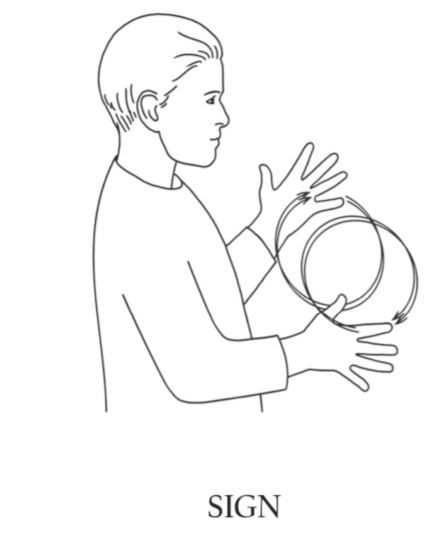

[6] Is also worth noticing the high contrast amid the graphic assertions from Elsevier and Sci-Hub and what each one represents and stands for in regard to power and information. I’ve always wondered about Sci-Hub’s logo genesis, because in this case the graph-isms go beyond the symbolic.

[7] I’m curious about the links and connections generated in the Master’s Program in Linguistics/Biblical Languages you were part in 2017, in a series of texts you’ve shown interesting readings about mythology, knowledge, theology and the ancient roots of copyright and intellectual property. You’ve been compiling information from figures like Колумба (or Saint Pirate), Hermes and antique repositories like the Library of Ashurbanipal to highlight one common denominator, the systematic exclusion of the premise “spread the word” and the consequent copy_paste counter-measure techniques to unlock this information_s.

Now that you discovered attractive routes to study information patterns and similarities through history, what is your future-vision to redefine file-sharing in an established .net regulated consumption landscape?

[8] We are in the middle of important changes at institutional, corporate and cultural levels in the context of Open Science and info-access, in June of this year MIT ended negotiations with Elsevier for a new contract, and recently the University of California also renewed negotiations launching open access resolutions with the dutch company. At the same time, many universities are inaugurating new protocols and initiatives to ensure wide and free access for academic resources.

Do you consider the recent measures taken by academic organizations are enough to abolish the paywall-economy?

[9] Earlier this year you were nominated for the John Maddox Prize by Fergus Kane after almost ten years of navigating into heavily corporate waters with Sci-Hub, one curious detail about the award is that it has support from the international scientific journal Nature, Nature’s news team covered Sci-Hub’s legal battle in New York courts with unfavorable handling.

What is your approach to this nomination and how significant could be for Sci-Hub’s potential?

Reference:

[1] Karaganis, J. Shadow Libraries (1st ed., p. 6). The MIT Press.