By Jan M. Ziolkowski

The Brooklyn-born R. O. Blechman, Bob to his intimates, qualifies officially as a nonagenarian on October 1, 2020. This blog post, despite being candleless and cakefree, celebrates the occasion, with more than enough social distancing to satisfy the strictest epidemiologist.

It fêtes the birthday boy by putting a little of his genius before a new generation, while simultaneously refreshing the memories of preceding ones about some of his achievements that may have slipped their minds.

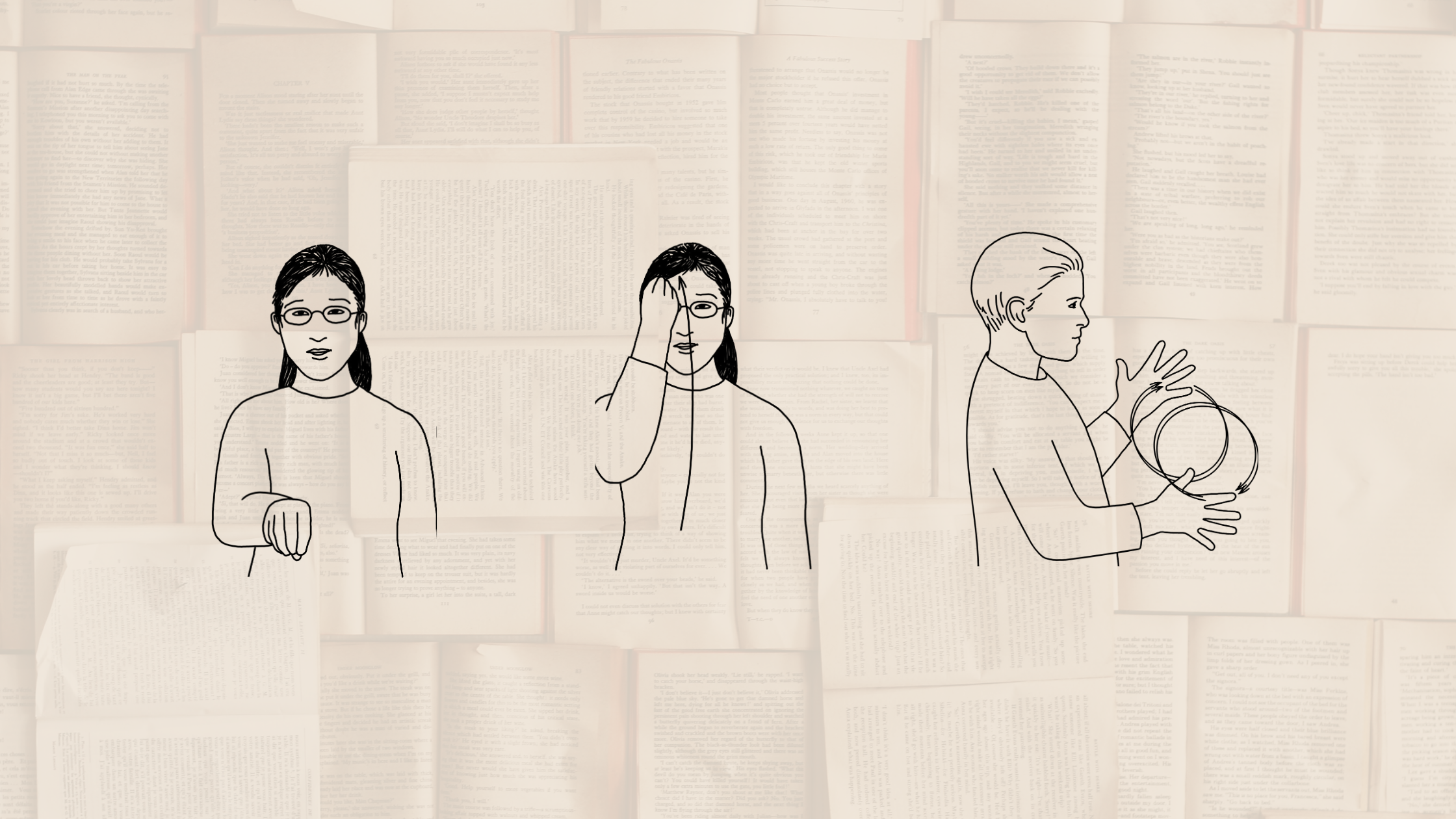

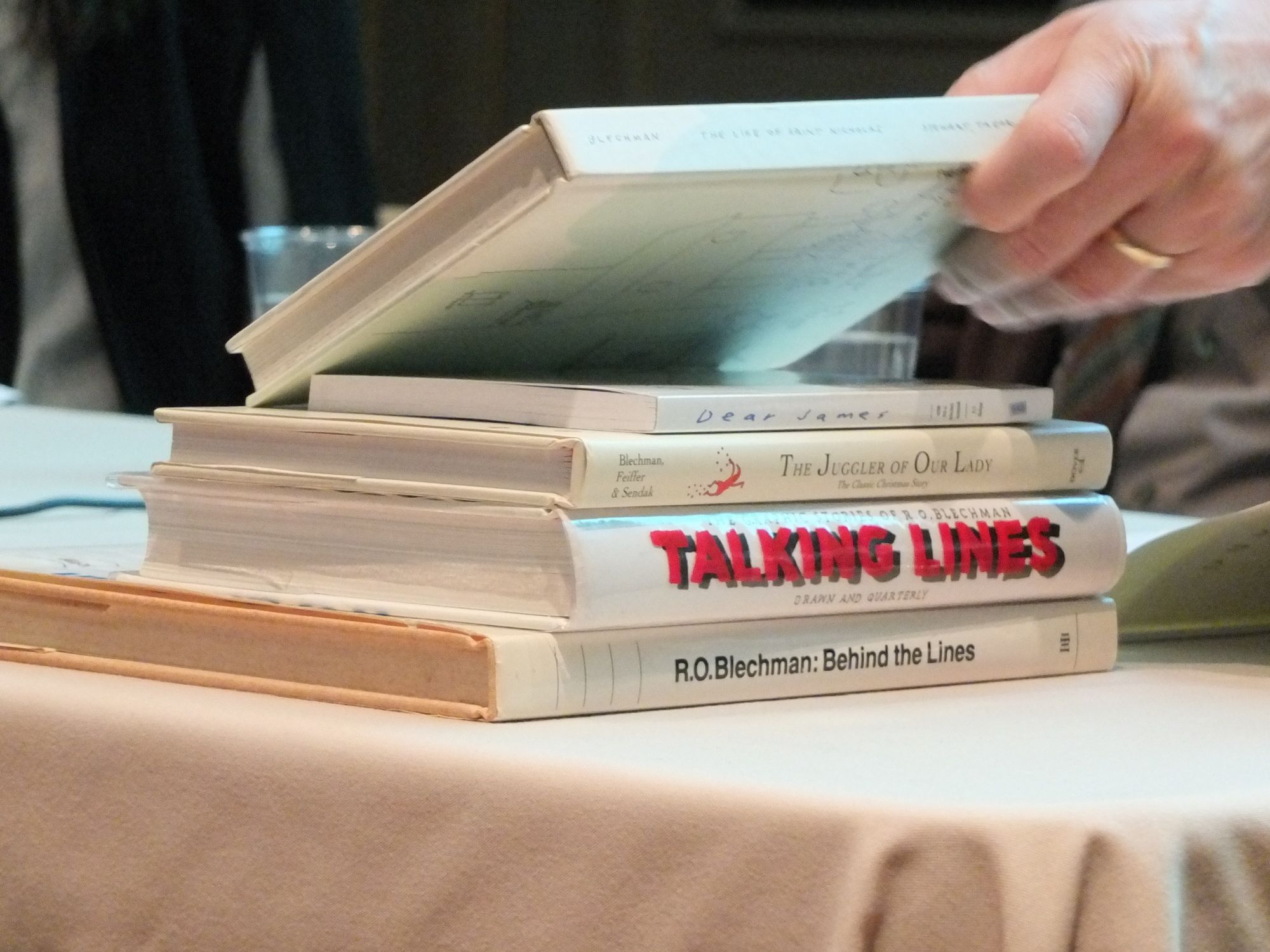

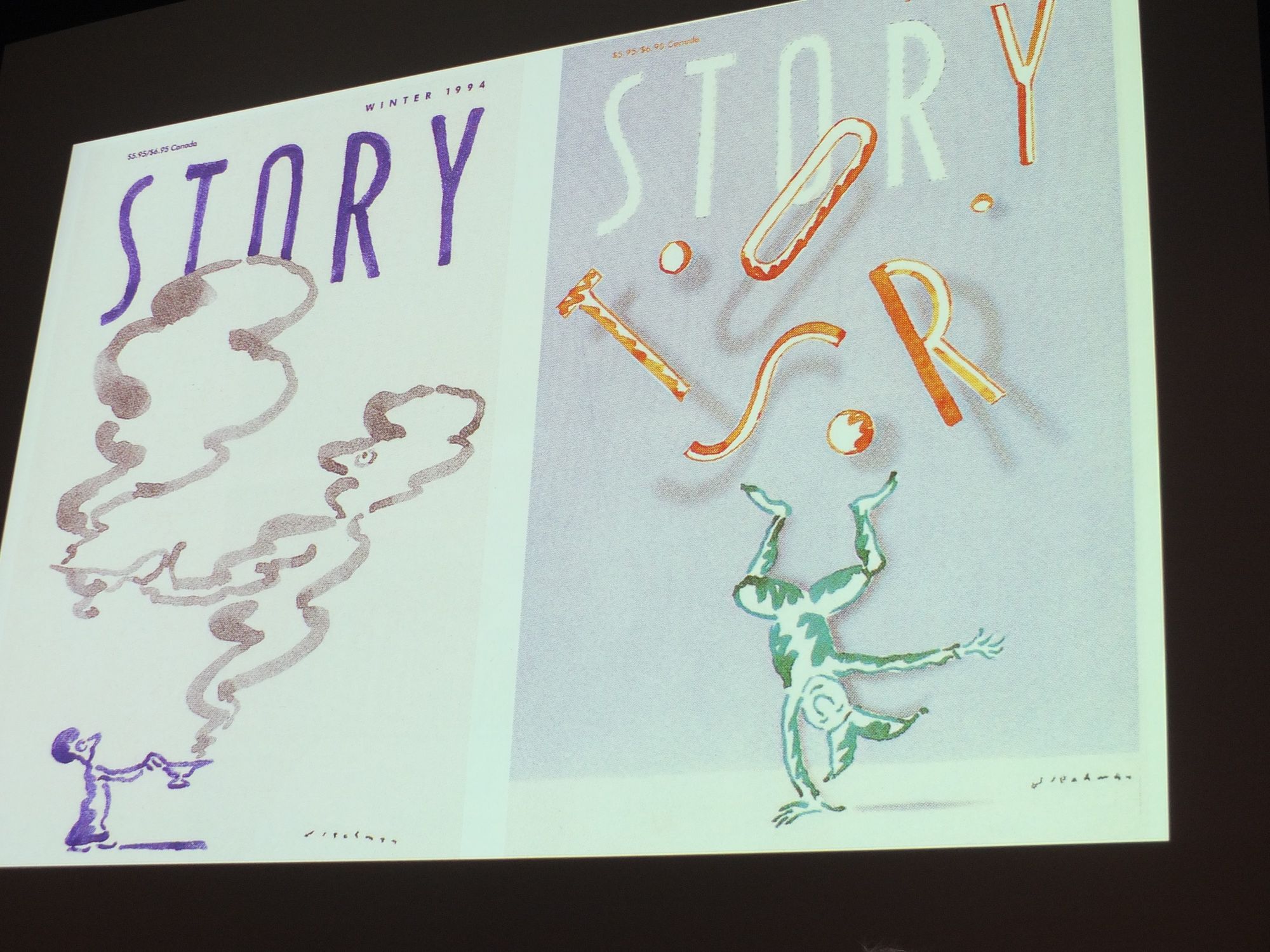

In nine decades, this artist has produced an oeuvre in which the slim book entitled The Juggler of Our Lady stands out as the first and foundational masterpiece—"surely the ground plan for everything that came after,” in the words of Maurice Sendak. Its creator has innovated at every step, while at the same time evidencing consistently a less-is-more minimalism that stamps his work immediately as both typically mid-century modern and unmistakably Blechmannian.

The volume was brought out in 1953, a year after Blechman graduated from Oberlin College. Through a schoolmate, he received an introduction to an art director at the trade press Henry Holt & Company. Among other items in his portfolio he displayed a graphic story from his undergraduate years. In response, he was urged to devise something suitable for the Christmas market. A friend of his suggested Anatole France’s The Juggler of Our Lady, with which Blechman immediately familiarized himself. For context he consulted Will Durant’s bestselling Age of Faith, then a mainstay of popular history on the Middle Ages. He roughed out a draft in one night and delivered the completed form a few days later to the publishing house.

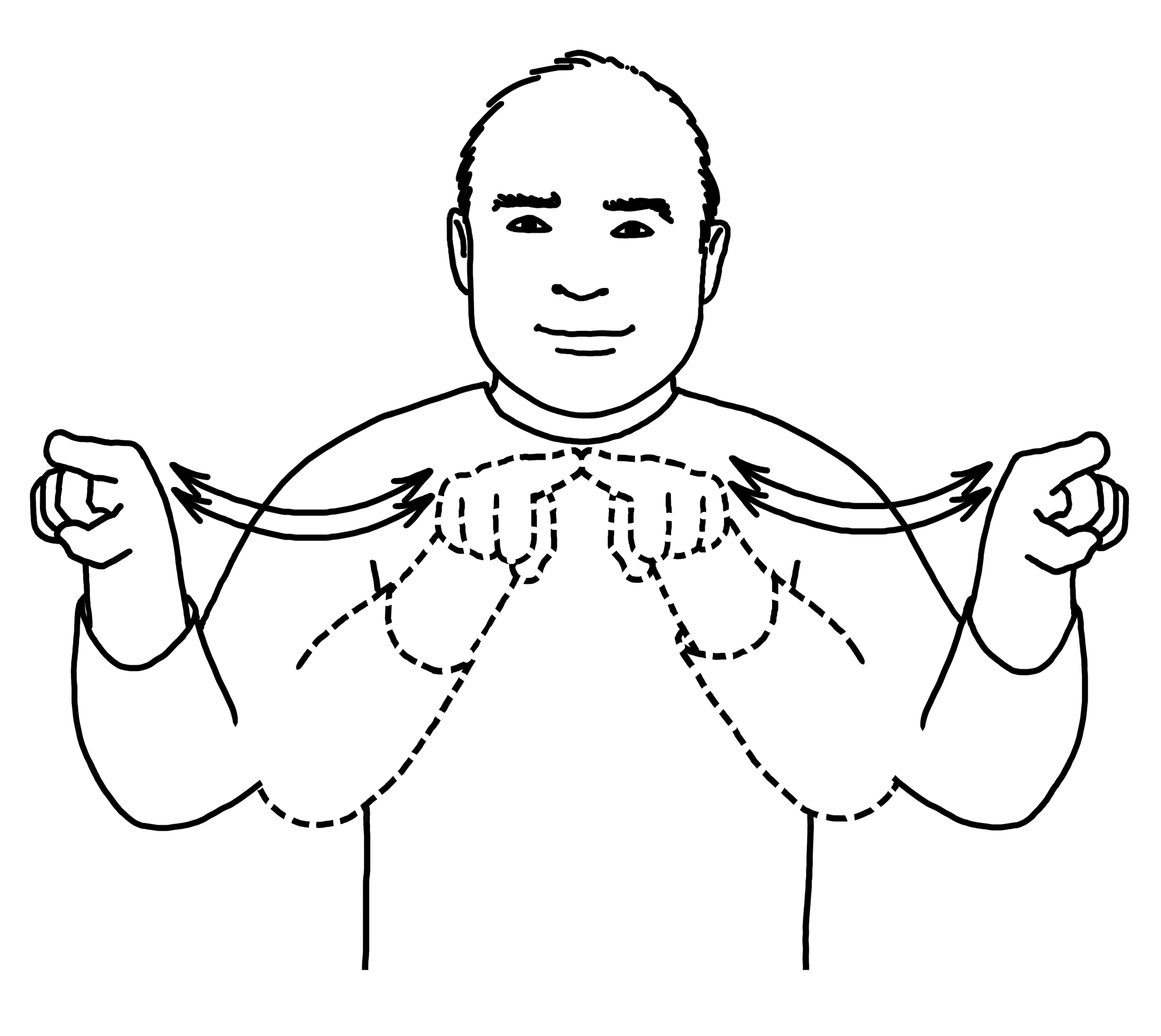

In Blechman, the hero has the new name of Cantalbert. After failing to impress the world through his juggling, the charmingly hapless performer enters a monastery in search of spiritual fulfillment. Yet his simplicity and lack of education make him a fish out of water. A series of crises reaches a head when the monks offer the gifts of their talents before a statue of Mary. In a Merry Christmas miracle, Cantalbert elicits from the Mother of God positive acknowledgment for his juggling.

The latest reprint, published in 2015, bears the subtitle The Classic Christmas Story. Those four words are not as straightforward as they appear. For starters, the subtitle of the first edition and its reissue in 1997 was A Medieval Legend. Sure, the next page identifies it as “A sort-of Christmas story.” Yet the narrative did not originally have its seasonality baked into it, not in its medieval original and not in Anatole France’s short story either.

To complicate matters even more, we could consider that its author is Jewish by background. If the book is a Christmas tree, its trimmings are wonderfully odd: a foreword by Jules Feiffer, who calls it a “miniature masterpiece,” leads into an introduction by Maurice Sendak. This triumvirate points not to England of ye olde or Europe of yore, but to Manhattan in the full swing of the American century.

To tack back to the subtitle, The Juggler of Our Lady has a much harder time passing muster as a classic in the changing cultural canon of the twenty-first century than it did from the fin de siècle through the first half of the twentieth. When Blechman composed his proto-graphic novel, Anatole France’s story belonged the bedrock for French instruction in the U.S. Adapted for American audiences, the tale was performed on the radio each December in multiple versions.

Now that nearly seventy years have passed, French has long lost the prestige and preeminence that it formerly possessed among foreign languages, Anatole France’s literary stature and Nobel prize have gone forgotten, and the holiday broadcasts have become a thing of the past. The story shows its greatest vitality in children’s literature, but the best-known iteration by the late Tomie dePaola dispensed with the formerly familiar title in favor of The Clown of God.

For all the hurdles that have been raised, my bet is confident that Blechman’s The Juggler of Our Lady will live on. For one thing, his creation helped to bring into being a thriving genre. A graphic novel, by its very nature, depends upon relating a series of events in a text that can sustain and be sustained by illustration. In this case, the storyline has at its heart the importance of following a passion—and an urgent need to stand out and accomplish something. The juggler is at once sublimely humble and supremely ambitious, and the drawing is complex in its simplicity, just as the calligraphy is rock-steady in its waviness.

Another factor favoring the book is the marvelous nine-minute animated short that was released in 1957, likewise entitled The Juggler of Our Lady. It fills out the story by alluding to the Cold War, the Korean War, and McCathyism; it takes cartoon art to altogether new heights; and, to boot, it benefits from voiceover by Boris Karloff, after his heyday in horror films but before the animation of Dr. Seuss’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas. Though not often viewable with the wide-screen or color quality of early prints, it richly rewards those who can find it online or otherwise. Go, YouTube!

The same return for effort holds true for every bit of Blechmania that can be found in print or in animation.

Anyone who watched television in 1967 will recall with a smile or even a laugh the commercial in which to advertise Alka-Seltzer a stomach was interviewed about its digestive suffering. From around the same time were interstitials for CBS and the 1966 Christmas message for the same television network. Turning from TV broadcasts to magazines and newspapers, those old enough will remember our artist’s lines across later decades to the present. Think for instance with joy of the twin towers of the World Trade Center on the cover of The New Yorker of April 29, 1974, with grief of them in The New York Times op-ed page of September 14, 2001.

Now is not the time nor this the place to embark upon a catalogue raisonné of everything Bob Blechman has given us, but instead to express best wishes for continued productivity—so that at least for him we can consider the third decade of the twenty-first century the nifty nineties. More than ever, the world needs his fierce integrity, along with his relentless care about words and images.

Smiles and wisdom will not fix all ills in this time of pandemic—but they do the soul good.

Photos free so long as attributed: see http://www.bguthriephotos.com/graphlib.nsf/keys/2018_DC_Blechman_181103

Read Jan Ziolkowski's six-volume set, The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity (2018), freely accessible to read and available to buy at Open Book Publishers.