Here we share our draft response to the UKRI Open Access consultation. We will answer the questions that pertain to books and chapters, since that is our area of expertise.

Please annotate this post with any thoughts or relevant evidence you wish to share (we have integrated Hypothes.is to make this easy to do). Please also feel free to draw on our answers when writing your own response, if you are submitting one.

If you would like to express support for the arguments made here, you can sign this Google doc, which will be submitted as part of our response. If we make any changes to this draft response, they will be posted on this blog by noon on Thursday 28 May (24 hours before UKRI's deadline) in case you wish to see the final version before signing.

Section B: Monographs, Book Chapters and Edited Collections

Q33. To what extent do you agree or disagree that the types of monograph, book chapter and edited collection defined as in-scope and out-of-scope of UKRI’s proposed OA policy (see paragraphs 96-98 of the consultation document) are clear?

Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree / Don’t know / No opinion.

If you disagree, please explain your view (2,000 characters maximum, approximately 300 words).

The definitions as given are often subjective and loosely phrased.

- A trade book ‘has a broad public audience’: for this to be established, we strongly suggest specific thresholds for the ‘higher print runs’ and ‘changes in the price point’. We believe that an author or publisher who want to make use of this (or any) exception should be obliged to provide the data – in this case: title, price point, proposed print run – so that UKRI can monitor and review the exceptions after a certain period, to see how much they are used. (See Q58 for more on exceptions.) A trade exception is presumably based on a fear of publishers losing revenue – although this fear is not well substantiated (see Q40). We welcome the stipulation on p.27 that if a trade book is the only output from UKRI-funded research it will fall within the policy’s scope. We believe this will help to discourage use of the exception as a means to avoid the OA requirement.

- Books that ‘require significant reuse of third-party material and where alternative arrangements are not a viable option’ – how will it be established whether a book ‘requires’ significant reuse of third-party content? What would it mean for ‘alternative arrangements’ to be ‘viable’ or not in practice? (See Q44-46 for more on whether reuse of third-party material is a barrier to OA publication.)

- Where ‘the only suitable publisher in the field does not have an OA programme’ – how will ‘only suitable’ be established? What is to stop an author claiming that a publisher is the ‘only suitable’ outlet for reasons of prestige?

- For scholarly editions – could the introductory essay be published OA, if the edition itself is not? These might be valuable resources at GCSE or A-Level, for example, especially at a time when many secondary-school budgets are under pressure.

Q34. Should the following outputs be in-scope of UKRI’s OA policy when based on UKRI-funded doctoral research?

a.Academic monographs Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion

b.Book chapters Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion

c.Edited collections Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion

Please explain your view (1,350 characters maximum, approximately 200 words).

Yes to all – in theory. But support is needed: if the author no longer has access to an institutional repository they need a suitable place to deposit the accepted MS (if Green OA is the route – see Q41, 42, 55 & 61). They should also be granted funding to cover the costs of publication for Gold, if this is necessary (see Q42, 53 and 61 on BPCs) or supported in finding a suitable publisher that does not levy such charges.

The language is loose again here: what does ‘based on’ mean precisely? Anything that draws on doctoral research in any way?

There is a significant benefit to this stipulation: at the moment, many people post-PhD are anxious about whether they should embargo their thesis, in the belief that an openly available thesis might hamper their chances of getting a book contract. This perverse incentive to restrict access to research should be addressed urgently. If people are aware that any outputs from their UKRI-funded thesis will have to be published OA, and if they are supported in doing so, this anxiety ought to be allayed and more theses stored OA in institutional repositories with no embargo.

Q35. To what extent do you agree or disagree that UKRI’s OA policy should include an exception for in-scope monographs, book chapters and edited collections where the only suitable publisher in the field does not have an OA programme?

Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree / Don’t know / No opinion.

Please explain and, where possible, evidence your view (1,350 characters maximum, approximately 200 words).

This provision is highly subjective and open to abuse. What does the ‘only suitable publisher’ mean and how is this to be established? Can an example be given of any press that is the ‘only suitable’ publisher for any academic book? As it stands, this appears to be a significant loophole for authors who might wish to be unencumbered by the OA requirement when choosing their publisher.

In terms of the ability to take on more demanding projects, Open Access presses are often highly innovative and open to proposals that are more unusual and technically adventurous than the standard academic monograph – see for example our own track record of innovative publications.

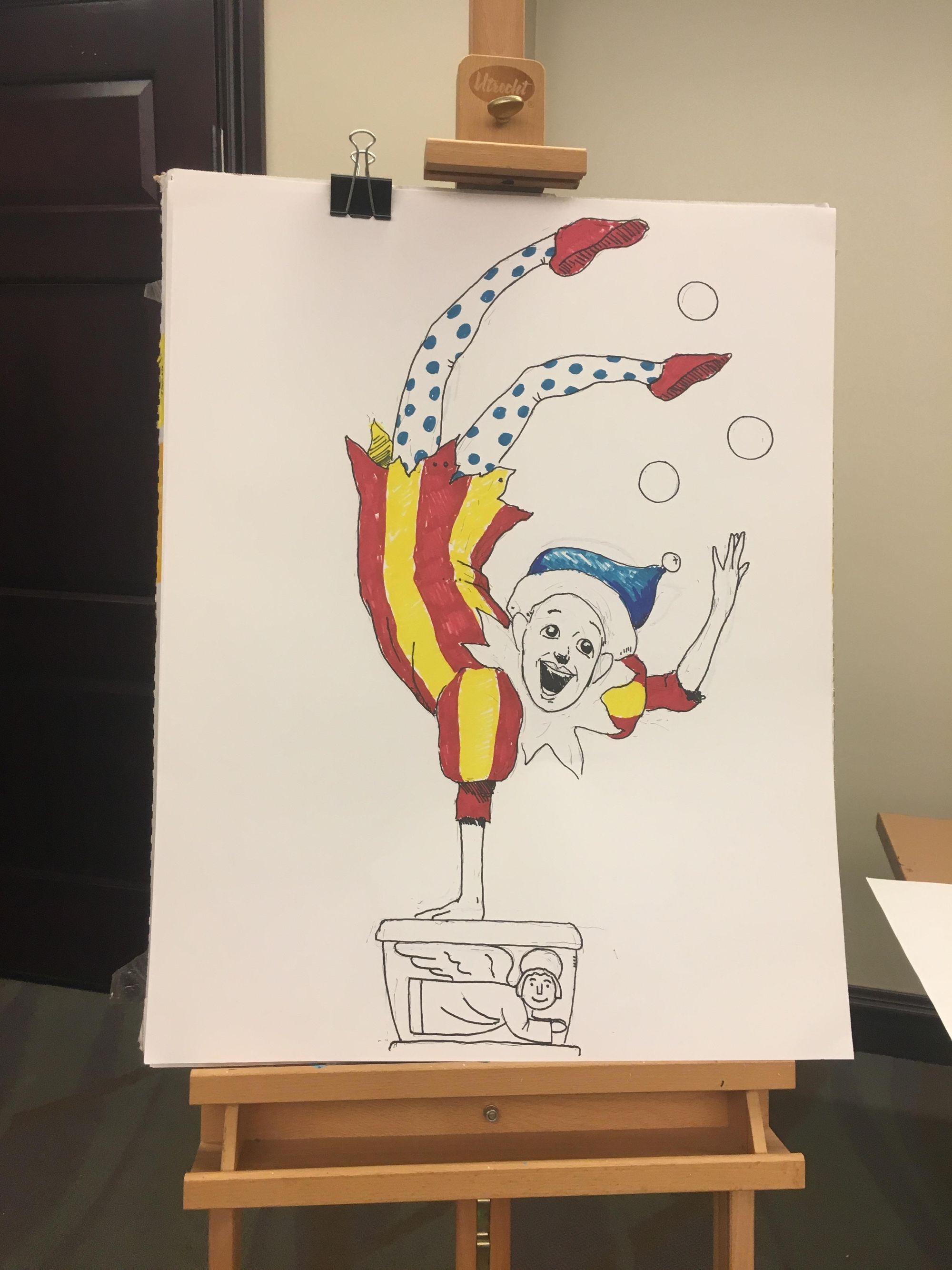

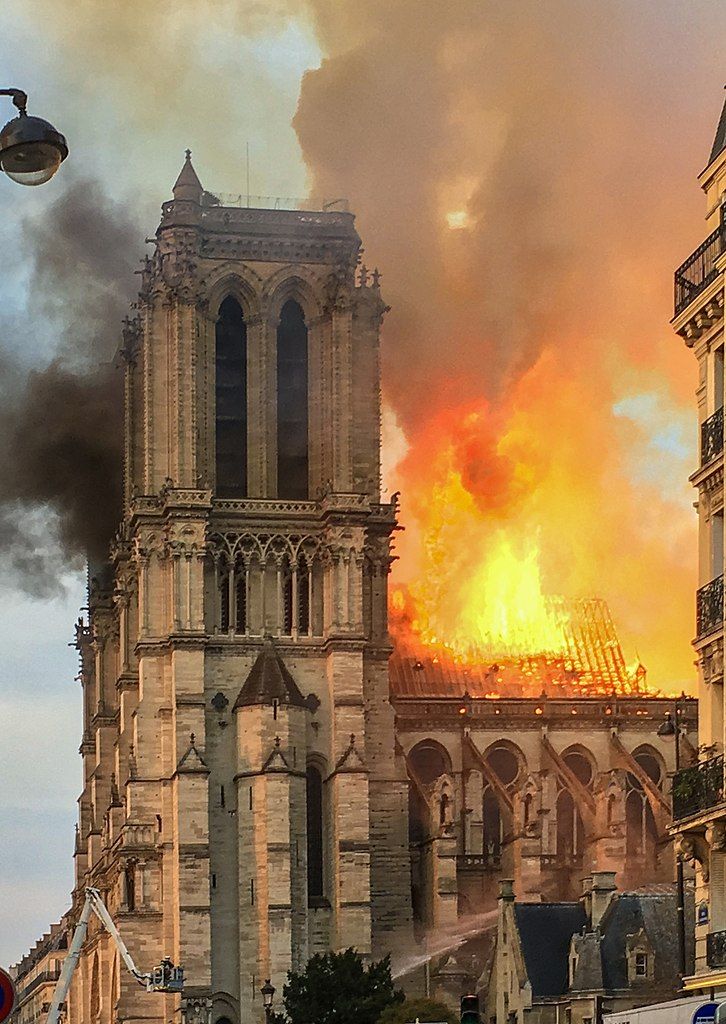

They are also often able to respond more nimbly to requests for speed and volume – see for example our series The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity by Jan M. Ziolkowski, six books published over seven months that also included over a thousand images.

Further: why should access to UKRI-funded research be held back because a particular publisher doesn’t offer Open Access? We believe this exemption should be scrapped entirely.

Q36. Are there any other considerations that the UK HE funding bodies should take into account when defining academic monographs, book chapters and edited collections in-scope of the OA policy for the REF-after-REF 2021?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

Q37. Regarding monographs in-scope of UKRI’s proposed OA policy, which statement best reflects your view on the maximum embargo requirement of 12 months?

a.12 months is appropriate

b. A longer embargo period should be allowed

c. A shorter embargo period should be required

d. Different maximum embargo periods should be required for different discipline areas

e. Don’t know

f. No opinion

Please explain and, where possible, evidence your answer. If you answered b, c or d please also state what you consider to be (an) appropriate embargo period(s) (1,350 characters maximum, approximately 200 words).

Our view, as an OA book publisher that has never imposed an embargo, is that an embargo of any length is an unnecessary restriction on access.

There should be a very good and well-evidenced argument for embedding restrictions on access into an Open Access policy. But on the contrary, in the field of journal publishing, SAGE has argued there is no evidence that zero embargo hurts subscriptions, while Emerald have scrapped embargoes and reported positive outcomes. See Q40 for further evidence that an embargo is unnecessary.

Without evidence for both the need and effectiveness of an embargo of a given length, it is an arbitrary restriction imposed in an attempt to placate worried publishers. If allowed, this must be subject to review after a certain period of time, when the impact of the OA policy is better known (see Q58).

Further: if an OA book is released only after an embargo, a publisher should be obliged to raise awareness of the OA version at the time of its release, and link to it prominently on their website. Otherwise embargoed OA risks being invisible OA.

Q38. Regarding book chapters in-scope of UKRI’s proposed OA policy, which statement best reflects your view on the maximum embargo requirement of 12 months?

a.12 months is appropriate

b. A longer maximum embargo period should be allowed

c. A shorter maximum embargo period should be required

d. Different maximum embargo periods should be required for different discipline areas

e. Don’t know

f. No opinion

Please explain and, where possible, evidence your answer. If you answered b, c or d please also state what you consider to be (an) appropriate embargo period(s) (1,350 characters maximum, approximately 200 words).

As for Q37: we advocate zero embargo. There is no strong argument for embedding this restriction on access into an Open Access policy.

Q39. Regarding edited collections in-scope of UKRI’s proposed OA policy, which statement best reflects your view on the maximum embargo requirement of 12 months?

a.12 months is appropriate

b. A longer embargo period should be allowed

c. A shorter embargo period should be required

d. Different maximum embargo periods should be required for different discipline areas

e. Don’t know

f. No opinion

Please explain and, where possible, evidence your answer. If you answered b, c or d please also state what you consider to be (an) appropriate embargo period(s) (1,350 characters maximum, approximately 200 words).

As for Q37 and 38: we advocate zero embargo. There is no strong argument for embedding this restriction on access into an Open Access policy.

Q40. Do you have any specific views and/or evidence regarding different funding implications of publishing monographs, book chapters or edited collections with no embargo, a 12-month embargo or any longer embargo period?

Yes / No.

If yes, please expand (2,000 characters maximum, approximately 300 words). Please note that funding is further considered under paragraph 110 of the consultation document (question 53).

The sources cited below conclude that Open Access publication does not significantly harm sales – even with no embargo.

Ronald Snijder, “The Deliverance of Open Access Books: Examining Usage and Dissemination” (doctoral thesis, Leiden University, 2019), https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/68465

‘open access did not have a large effect on monograph sales, positive nor negative.’ (p.200)

Eelco Ferwerda, Ronald Snijder, and Janneke Adema, “OAPEN-NL. A Project Exploring Open Access Monograph Publishing in the Netherlands: Final Report” (The Hague: OAPEN Foundation, October 2013), http://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/OAPEN-NL-final-report.pdf. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273450141_OAPEN-NL_-_A_project_exploring_Open_Access_monograph_publishing_in_the_Netherlands_Final_Report

‘OAPEN-NL found no evidence of an effect of Open Access on sales.’ (p.4)

Eelco Ferwerda, Ronald Snijder, Brigitte Arpagaus, Regula Graf, Daniel Krämer, Eva Moser, ‘The impact of open access on scientific monographs in Switzerland. A project conducted by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF)’ (OAPEN-CH) DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1220607

‘Statistically, open access did not have a negative influence on the sales figures for printed books.’ (p. 7)

Rupert Gatti, ‘Introducing data to the open access debate: OBP’s business model (part three)’ 15 October 2015, https://blogs.openbookpublishers.com/introducing-data-to-the-open-access-debate-obps-business-model-part-three/

‘Overall it seems that we are selling roughly the same number of books as legacy publishers.’

Ronald Snijder, ‘The profits of free books: an experiment to measure the impact of open access publishing,’ Learned Publishing, 23:293–301, https://doi.org/10.1087/20100403

Rachel Pells, ‘Open access: “no evidence” that zero embargo periods harm publishers’, Times Higher Education, 23 April 2019, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/open-access-no-evidence-zero-embargo-periods-harm-publishers

We have never imposed an embargo on the publication of any of our books, and yet sales are still our largest income stream, and the greatest volume of sales still occurs in the first year of a book’s publication. Our experience, as a successful OA book publisher of twelve years’ standing, demonstrates that embargoes are unnecessary.

Q41. To what extent do you agree that self-archiving the post-peer-review author’s accepted manuscript should meet the policy requirement?

Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree / Don’t know / No opinion.

Please explain your view (1,350 characters maximum, approximately 200 words).

Books are complex objects, involving significantly more editorial and production work than an article. For many of our books, the 'author's accepted manuscript' would be a poor substitute, particularly:

- books requiring significant editorial work, e.g. edited collections with a mix of authors of varying ability in English;

- books such as Kate Rudy's Image, Knife, and Gluepot (2019) in which the argument depends on high-quality images, not reproduced in the MS.

Will the MS be cited, especially if it is without page numbers? How discoverable is it, stored in a repository? (See Q54.) Not all publishers review the entire MS: will it then be deposited in its entirety?

Green OA risks being poor quality, hard to find, and little used: bluntly, inadequate. If sanctioned, these problems must be mitigated as far as possible:

- The MS must include author edits made after peer-review and it must be the entire MS: this should be explicit. It must include page numbers.

- The Green version must be linked from the publisher’s website and have a DOI. See Q42, 54 and 55 for further ways to enhance discoverability.

Publishers have an obligation to support their author, including with Green OA. This route must not permit the publisher to do nothing.

Q42. Regarding monographs, book chapters and edited collections, are there any additional considerations relating to OA routes, deposit requirements and delayed OA that the UK HE funding bodies should take into account when developing the OA policy for the REF-after-REF 2021?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

If yes, please expand (2,650 characters maximum, approximately 400 words). Please see paragraphs 29-31 of the consultation document before answering this question.

Since there are many times more books included in the REF than are funded by UKRI, the impact of an OA policy for these books will have a proportionally greater impact and benefit; the challenges will likewise increase.

As we see it, there are two key hurdles to be overcome: 1) that neither the UKRI nor REF policies should be the means of diverting large amounts of public money to pay Book Processing Charges for individual books (see Q53), and 2) a low-quality, undiscoverable Green route should not be enabled as a low-cost, low-effort alternative.

We therefore propose ways UKRI could help to support the growth of BPC-free Gold OA, and how it could improve the quality and discoverability of Green OA books and chapters.

Ways to enhance BPC-free Gold are detailed in Qs 42, 53 and 61. Broadly, they involve supporting projects such as COPIM to create open, community-governed infrastructures and systems that bring down the costs of OA publishing for all, and help to build alternative funding systems, such as support from libraries that will no longer be paying for access to so much closed content. We recommend UKRI asks for transparency from publishers who charge BPCs about what costs they cover and why revenue is insufficient to meet them. We suggest UKRI emphasises it is not willing to support BPCs as a means of funding OA long-term, and that it should consider seriously the ‘scaling small’ model proposed and exemplified by the ScholarLed publishers as a means to build capacity (see Q66).

If Green OA is in scope, see Qs 41, 54 & 55 for details of how its quality and discoverability could be improved. Discoverability is a serious problem for institutional repositories. Deposited work is generally not catalogued in academic libraries apart from the institution’s own (and not always effectively then). It is doubtful the general public is widely aware of it.

Broadly, we recommend: provide page numbers to enable clear citations, and a full text with author edits made in the light of peer-review feedback; ensure that each Green OA MS has a DOI and is stored and shared on a central UKRI platform, with metadata sent to all UK academic libraries; and mandate that publishers must provide a prominent link to the OA version on the book’s home page, and publicise its release if an embargo is applied.

Q43. To what extent do you agree or disagree with CC BY-ND being the minimum licensing requirement for monographs, book chapters and edited collections in-scope of UKRI’s proposed OA policy?

Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Don’t know / No opinion.

Please explain and, where possible, evidence your view (1,350 characters maximum, approximately 200 words).

Reuse is an important component of Open Access. We support minimal restrictions wherever this is appropriate: CC BY is the licence for most of our books.

CC BY-ND excludes the reuse and remixing of content, which lies at the heart of various groundbreaking OA experimental publishing projects such as Open Humanities Press’s Jisc-funded Living Books about Life or its European-Commision-funded Photomediations: An Open Book.

CC BY-ND would also hinder translation (e.g. Economic Fables by Ariel Rubinstein has been successfully translated into Chinese thanks to its CC BY licence) and the extraction of chapters for use in course packs. (See also https://creativecommons.org/2020/04/21/academic-publications-under-no-derivatives-licenses-is-misguided/)

However, there are occasions when ND or another licence is suitable, including CC BY-NC: e.g. when a book reproduces culturally sensitive content (as is common in Anthropology, for example), which it would be inappropriate to see commercialised. See https://blog.scholarled.org/ownership-control-access-possession-in-oa-humanities-publishing/

We argue that the full range of CC licences should be in scope: CC BY the default, with the ability to make the case for a more restrictive licence. The author or publisher should have to justify to UKRI in writing the use of a more restrictive licence.

Q44. To what extent do you agree or disagree that UKRI’s OA policy should include an exception for in-scope monographs, book chapters and edited collections requiring significant reuse of third-party materials?

Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree / Don’t know / No opinion.

Please explain your view (1,350 characters maximum, approximately 200 words).

We do not believe an exception is necessary. If any such exception were granted, it would need to be tightly defined and subject to monitoring as outlined in Q58.

There is a prevailing myth that third-party materials create an insurmountable problem for Open Access. We believe our catalogue of OA books demonstrates otherwise. E.g.:

Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art: New Perspectives edited by Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow (2017) (89 images reproduced in the book)

Image, Knife, and Gluepot: Early Assemblage in Manuscript and Print by Kathryn M. Rudy (2019) (137 images reproduced in the book)

Piety in Pieces: How Medieval Readers Customized their Manuscripts by Kathryn M. Rudy (2016) (209 images reproduced in the book)

The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity by Jan M. Ziolkowski (6 vols.) (2018) (1,467 images reproduced across the six volumes)

Essays on Paula Rego: Smile When You Think about Hell (2019) by Maria Manuel Lisboa (181 images reproduced in the book)

Dickens’s Working Notes for Dombey and Son by Tony Laing (2017)

(includes facsimile images of every page of Charles Dickens’ notes for his novel Dombey and Son, from the Forster Collection in the National Art Library in the V&A Museum).

Questions 45-46 concern how ‘significant reuse’ may be defined.

Q45. To what extent do you agree or disagree that if an image (or other material) were not available for reuse and no other image were suitable, it would be appropriate to redact the image (or material), with a short description and a link to the original?

Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree / Don’t know / No opinion.

Please explain your view (1,350 characters maximum, approximately 200 words).

We have done this with two of our books by Kathryn Rudy, Piety in Pieces (2016) and Image, Knife, and Gluepot (2019) with great success. In both, permanent links were given to images that were freely available on the web, rather than paying to reproduce them in the books (in addition to the many images that were reproduced in the book). This practice was part of Rudy’s argument, which called attention to the difficulty of manuscript study when institutions have restrictive policies around image reproduction. It was commended in reviews (e.g. see Elizabeth Savage, The Library, 19:2 (2018), 230-31).

Rudy used funding to make many more images freely available online and then linked to them, rather than using the money to publish them. She thus made these resources freely available online for others. This is a practice that might be taken up more widely.

Rudy’s books are highly valued by readers. Piety in Pieces has been accessed over 10,000 times and Image, Knife and Gluepot has been accessed over 2,000 times. They have been extremely well reviewed and Piety in Pieces won the 2017 Choice Review’s Outstanding Academic Title.

We have since taken this approach with other books.

Q46. Do you have a view on how UKRI should define ‘significant use of third-party materials’ if it includes a relevant exception in its policy?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

If yes, please expand (2,000 characters maximum, approximately 300 words).

As demonstrated in Q44, a large amount of third-party material does not necessarily present a barrier to OA publication—so a definition by volume would be inadequate.

The premise that third-party material is automatically a hindrance is flawed. The issue therefore is not how ‘significant’ or otherwise the usage is, but whether the necessary material can be sourced and licensed for use in an OA book, or not. This depends on a number of factors, including the stipulations of the copyright holder, the funds available (sometimes), and the extent to which the publisher is prepared to assist the author in successfully sourcing appropriate images.

There is a wealth of openly available material, increasing all the time (see p.34 of our Author’s Guide for a list) and there are steps UKRI could take to swell these stores (see Q47).

Sometimes, third-party material can be acquired for an OA book in the same way as for a closed-access book. The fact that the book will be Open Access can make it easier, because one can argue that the book is being disseminated for the benefit of all, rather than simply for profit. Sometimes it is possible to find appropriate alternatives that are openly licensed, and sometimes the required material is already openly available.

Successfully acquiring third-party material requires the publisher to work closely with the author, and to support them in liaising with copyright holders or searching open repositories to obtain suitable material. It would be much easier to invoke a ‘significant use’ exception and not do so.

We would therefore argue against an exception of this nature. Instead, if third-party material is genuinely an insuperable obstacle to OA publication, the author or publisher should have to seek an exception in writing from UKRI.

Yes / No.

If yes, please expand (1,350 characters maximum, approximately 200 words).

There are two ways UKRI could support authors and publishers with third-party material.

UKRI has an opportunity to take a lead in growing open image repositories. This OA policy demonstrates that Open Access to research has government support. UKRI is therefore uniquely positioned to have influential conversations with national institutions—our museums, libraries, galleries—about openly licencing the material in their collections for the benefit of academic research. UKRI could also collaborate with other funders, e.g. Wellcome Trust and Coalition S, towards the same goal. Access to third-party material is an international problem—there should be collective solutions and UKRI could help to bring them about. This data from OpenGLAM demonstrates the possibilities: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1WPS-KJptUJ-o8SXtg00llcxq0IKJu8eO6Ege_GrLaNc/edit#gid=1216556120

The other area is fair practice. Legal precedents support the argument that the ‘quotation exception’ to copyright infringement can apply to any media, as long as the ‘quotation’ is made with the intention of ‘entering into a dialogue’ with the relevant material. Cover images or decoration would be out of scope, but anything crucial to the argument (we might call it ‘significant use’) would fall within it. Fair practice has been limited by cautious publisher behaviour. UKRI could help to support a change here.

Q48. Regarding monographs, book chapters and edited collections, are there any additional considerations relating to licensing requirements and/or third-party materials that you think that the UK HE funding bodies should take into account when developing the OA policy for the REF-after-REF 2021?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

If yes, please expand (2,650 characters maximum, approximately 400 words). Please refer to paragraphs 29-31 of the consultation document before answering this question.

As mentioned, the REF will involve dealing with a greater volume of books to be made OA. This strengthens arguments that might be made to national cultural institutions about the importance of making third-party material related to their collections openly available to academic researchers for OA publication. It should be noted that a much wider use of their collections in this way could result in greater awareness of what these institutions have to offer to visitors and visiting scholars, as well as the broader cultural contribution it would make.

Q49. Which statement best reflects your views on whether UKRI’s OA policy should require copyright and/or rights retention for in-scope monographs, book chapters and edited collections?

a. UKRI should require an author or their institution to retain copyright and not exclusively tree ansfer this to a publisher

b. UKRI should require an author or their institution to retain specific reuse rights, including rights to deposit the author’s accepted manuscript in a repository in line with the deposit and licensing requirements of UKRI’s OA policy

c. UKRI should require an author or their institution to retain copyright AND specific reuse rights, including rights to deposit the author’s accepted manuscript in a repository in line with the deposit and licensing requirements of UKRI’s OA policy

d. UKRI’s OA policy should not have a requirement for copyright or rights retention

e. Don’t know

f. No opinion

Please explain and, where possible, evidence your answer. If you selected answer b or c, please state what reuse rights you think UKRI’s OA policy should require to be retained (2,000 characters maximum, approximately 300 words). It is not necessary to repeat here, in full, information provided in response to question 12. Please note that views are not sought on whether institutions should hold the copyright to work produced by their employees as this is subject to Section 11 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and institutional copyright policies.

We believe authors should retain control of their work. It should not be up to a publisher to mandate how an author's work is reused (or not). There is no need for an author to give up copyright or any reuse rights for a publisher to distribute their research.

We have a non-exclusive licence to publish an author’s work in several formats (usually paperback, hardback, EPUB, MOBI, PDF, HTML and XML, with the latter three editions being Open Access). We do not ask for copyright or reuse rights from the author. We have published over 170 academic books, and this has worked perfectly well. No author has abused it.

Q50. Regarding the timing of implementation of UKRI’s OA policy for monographs, book chapters and edited collections, which statement best reflects your view?

a. The policy should apply from 1 January 2024

b. The policy should apply earlier than 1 January 2024

c. The policy should apply later than 1 January 2024

d. Don’t know

e. No opinion

Please explain and, where possible, evidence your answer. If you selected b or c, please also state what you consider to be a feasible implementation date (2,000 characters maximum, approximately 300 words).

As the consultation notes (p.5), the government adopted the position that publicly funded research should be made OA (with a preference for immediate OA) after the Finch report in 2012. By 2024, twelve years will have elapsed since then. Publishers should have been long preparing for a policy of this nature, and many have. There is no argument for further delay except ‘we haven’t taken this seriously until now’ and there is no sound reason to indulge negligence with further postponement.

We believe the proposal that the policy should apply to books contracted after 1 January 2024 is misguided. Instead, it should apply to books published after that date. (See Q52 for more on this.) It can take a number of years for books to progress from contract to publication. We are over three-and-a-half years from 1 January 2024 – time to react to an OA mandate – but if the policy only applies to books contracted after 1 January 2024, it would probably be two or three years later before we see any OA books published as a result of UKRI research. We will then be fourteen or fifteen years after the government adopted the position that publicly funded work should be published OA.

Most major publishers already have an OA programme, and many smaller publishers, such as the ScholarLed presses, are showing that this can be done now. Projects such as COPIM, due to finish late 2022, are putting in place the infrastructure and knowledge to assist smaller publishers to flip to OA.

The COVID-19 crisis is starkly revealing that open access to knowledge – to learn, to teach, to research – is imperative, and that our current systems of dissemination are piecemeal and inadequate. (See e.g. https://blogs.ifla.org/lpa/2020/04/30/2147/) Both ethically and financially, we cannot afford to keep waiting.

Q51. In order to support authors and institutions with policy implementation UKRI will consider whether advice and guidance can be provided. Do you have suggestions regarding the type of advice and guidance that might be helpful?

Yes / No.

If yes, please expand (2,000 characters maximum, approximately 300 words).

Any guidance should not neglect the reasons for this policy. Too frequently, Open Access is discussed in terms of compliance and becomes tedious bureaucracy, resented by researchers rather than embraced. The benefits of OA in terms of impact, engagement and global access should be highlighted.

Information about a wide range of publishers’ OA policies – particularly peer-review processes, the type and quality of OA editions they offer, and whether they charge a fee – should be provided. Sites like OAPEN and the DOAB are useful sources.

Advice should be given to help authors spot when they are being offered a sub-standard or desultory form of Open Access. They might consider:

- Are you able to retain your copyright and reuse rights?

- Are you able to choose from a range of CC licences, and are their implications explained clearly to you?

- Will your book be available in HTML or XML Open Access versions, as well as PDF?

- How will any non-OA editions of your book be priced? Has expected sales revenue been factored into any fees the publisher is charging?

- Does the publisher insist on an embargo period? If so, what distribution is permitted afterwards?

- What is the distribution strategy? Will the OA edition be accessible prominently on the publisher’s website? Will it be distributed to platforms like OAPEN, the DOAB and Google Books?

- Does the publisher provide usage statistics and if so, are they transparent about how these are obtained?

- What is the publisher’s policy on third-party content? Are they willing to support you in including this wherever possible?

- Will your book or chapter be issued with a DOI?

Resources should include information as in this guide we published in 2018, with aids such as a glossary of jargon, information about copyright and CC licences and a set of questions to ask publishers.

Q52. Regarding monographs, book chapters and edited collections, are there any other considerations that UKRI and the UK HE funding bodies need to take into account when considering the interplay between the implementation dates for the UKRI OA policy and the OA policy for the REF-after-REF 2021 OA?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

If yes, please expand (2,650 characters maximum, approximately 400 words).

As mentioned in Q50, an implementation date that takes the signing of the contract as its marker is unsatisfactory – because of the delay it would create, as previously argued, but also for monitoring purposes. This problem is exacerbated when all books submitted to the REF are the subject of the policy.

The date of the signing of the contract is not a piece of information that is made publicly available. It is not searchable in metadata. It is all but impossible for UKRI to monitor and for people to use when searching for books and chapters that they might reasonably expect to be Open Access. The date of publication, by contrast, is a standard piece of metadata and commonly used in book or chapter searches. It is a much more practical and useful marker of in-scope works.

Yes / No.

If yes, please expand (2,650 characters maximum, approximately 400 words).

We believe this policy should not simply funnel public money to pay Book Processing Charges for individual books. We have long argued that the BPC is an inequitable and unsustainable way to fund OA. It transforms a barrier to access into a barrier to participation and, if normalised, would restrict OA publication to the wealthy.

BPCs represent a price, not necessarily a cost. Our own activities demonstrate that it is possible to publish books that are available in multiple, high-quality OA editions from the date of publication, at a cost to us of around £5,000 a book, and without charging authors. Our biggest revenue stream to meet this cost is sales, despite the fact that we publish all our books simultaneously in OA editions. That significant income can be generated from the sale of OA books is also demonstrated by the research cited in Q40, and other presses have noted it too (e.g. see https://twitter.com/DrMammon/status/1179400555086716935).

We have published all our costs and revenues for the last financial year in a blog post [forthcoming: to be published prior to the 29 May deadline], along with a detailed breakdown of our business model, to demonstrate how other approaches than the BPC can be effective.

BPCs are a high price to achieve a limited outcome: one OA book per BPC. UKRI money would be much better invested developing systems and structures that render the BPC unnecessary. See e.g. COPIM, which is building open, community-governed infrastructures to bring down the costs of OA publishing and enable alternative funding streams. COPIM is also exploring alternative business models to support OA, and examining how to help non-OA publishers transition to OA. (For more on infrastructures, see Q54.)

Investments like this, which approach the dissemination of research as a complex ecosystem, rather than a series of fixed transactions, are a much more powerful and sustainable way to manage a major transition to Open Access.

If BPCs are to be paid out of UKRI funding, there should be transparency between publisher and funder about what the costs are, and why existing revenues cannot meet them. But in our view, UKRI should make clear to authors and publishers that UKRI is not prepared to support BPCs in the long term.

There might be a case for allocating funds to help authors cover the costs of reproducing third-party material, although see Q45, 46 and 47 for arguments about a better way UKRI could invest resources here.

Q54. To support the implementation of UKRI’s OA policy, are there any actions (including funding) that you think UKRI and/or other stakeholders should take to maintain and/or develop existing or new infrastructure services for OA monographs, book chapters and edited collections?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

If yes, please state what these are and, where relevant, explain why UKRI should provide support (2,650 characters maximum, approximately 400 words).

UKRI should develop a platform where it can host and share the OA outputs it has funded.

- The content will be in one place, not scattered across publishers’ websites or institutional repositories with varying standards of discoverability.

- UKRI would thus support and enhance the discoverability of its OA research and showcase the work it has funded.

- It should therefore be a condition of UKRI funding that UKRI has the right to host a copy of each funded work, and the publisher must allow UKRI to collect metadata sufficient for this purpose.

This is particularly important if a Green OA route for books is deemed to be in scope. Institutional repositories are not sufficient for the effective dissemination of OA works – a Green OA paper in a repository in Cambridge will not appear in a library catalogue in Leeds, and vice-versa. Tools such as Unpaywall can help people find OA versions of academic works, but readers should not be dependent on tools designed to mitigate an initial failure of discoverability.

A UKRI platform could host both Gold and Green OA outputs. It could ensure all its OA works have a DOI, and deliver metadata to (at least) all UK academic libraries (this is another area where COPIM is doing good work). Such a platform would also provide a repository for scholars who have left their institution, but are publishing work based on a UKRI-funded PhD.

One option is to host a UKRI collection on the non-profit platform OAPEN, as the Wellcome Trust has done. OAPEN can host OA books, record reliable usage metrics and deliver metadata.

There are a number of other organisations with whom UKRI might liaise to explore the development of infrastructure in fruitful ways, such as SCOSS and Invest in Open Infrastructure as well as initiatives like OPERAS-P. The COPIM project is a valuable source of expertise that UKRI could consult.

SCOSS aims to facilitate the security and sustainability of a global network of community-governed infrastructure projects, while Invest in Open Infrastructure is making the case for higher-education institutions to help support the systems that disseminate the research they produce, in ways other than paying publishers for content. These are organisations with which UKRI could forge relationships in order to support its OA strategy.

Q55. Are there any technical standards that UKRI should consider requiring and/or encouraging in its OA policy to facilitate access, discoverability and re use of OA monographs, book chapters and edited collections?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

Please expand (2,000 characters maximum, approximately 300 words).

As previously argued, UKRI must make sure that it isn’t possible for an OA version of a book or chapter to be buried in a repository. There should be minimum standards of discovery and presentation:

- metadata sufficient for readers to discover the work;

- use of Crossref DOIs that point to the OA version;

- a UKRI platform where funded OA works can be hosted (see Q54),

- standards for display on publishers’ websites, including

- OA versions clearly marked and linked to on a publisher’s website (for Green as well as Gold OA),

- filters on publishers’ websites enabling a search for OA publications.

Full-text URLs for content mining should be encouraged.

UKRI should also be thinking long-term about supporting a move away from the PDF format. PDFs are difficult to search and reuse. They put digital content into the format of a printed book, when it could and should go beyond that. We believe that readers will always value printed works, and our business model depends in part on their sale, but we also do not believe that digital content should necessarily be formatted in the same way as a print book. We believe UKRI should be supporting the development of machine-readable, XML-based content (see for example the freely available, open source tools and workflow we have developed to enable other publishers to convert EPUB editions into XML files, as we do). This might not be something that can realistically be demanded in the short term, but UKRI should be actively investigating how it can be made possible in the future.

Q56. Do you have any other suggestions regarding UKRI’s proposed OA policy and/or supporting actions to facilitate access, discoverability and reuse of OA monographs, book chapters and edited collections?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

Section C: Monitoring Compliance

Q57. Could the manual reporting process currently used for UKRI OA block grants be improved?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

Q58. Except for those relating to OA block grant funding assurance, UKRI has in practice not yet applied sanctions for non-compliance with the RCUK Policy on Open Access.Should UKRI apply further sanctions and/or other measures to address non-compliance with its proposed OA policy?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

Please explain your answer (2,000 characters maximum, approximately 300 words).

Withholding funding from the institution seems a reasonable measure if faced with repeated breaches of the policy, but UKRI should support institutions to equip their researchers with the tools to navigate the publishing landscape and successfully comply.

UKRI could also reward institutions. As mentioned in Q51, OA policies too often focus on compliance and sanctions at the expense of communicating the reasons why the policy is a good idea. Could an institution’s openness be assessed with the intention of rewarding good practice and celebrating high-quality, open work?

Throughout this response we have emphasised that, rather than allowing broad exemptions, UKRI should instead allow particular exceptions if reasonable, and monitor the extent of their use. We suggest these exceptions should be held in a publicly accessible database, so that anyone can see why this research is not made openly available. The use of exceptions should be monitored by UKRI, both to see if they continue to be necessary, and to consider whether they highlight particular areas of difficulty in complying with the OA policy that might be mitigated.

Q59. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the example proposed measures to address non-compliance with the proposed UKRI OA policy (see paragraph 119 of the consultation document)?

Strongly agree / Agree / Neither agree nor disagree / Disagree / Strongly disagree / Don’t know / No opinion.

Section D: Policy Implications and Supporting Actions

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

Please expand (2,650 characters maximum, approximately 400 words).

The most direct benefit to OBP, as an OA book publisher, would be if there were more authors looking to publish an Open Access book. More than this, however, we believe the UKRI OA policy could have significant benefits in helping to facilitate a cultural shift in academic book publishing in the UK.

The current incentives in terms of hiring and promotion in UK universities do not encourage the prioritisation of access when authors are making publishing decisions. The UKRI OA policy will make access a much higher priority for both academics and publishers, and there is an opportunity here to hugely strengthen access to research undertaken in the UK.

As a scholar-led publisher, we are also members of the research and teaching communities. More books openly available to read will benefit us all (see this recent IFLA interview with academic librarian Johanna Anderson about the barriers and expense involved in trying to arrange access to academic books during the COVID-19 crisis). The problem of access is particularly noticeable now that members of wealthy institutions in the Global North are unable to use their libraries, and it is multiplied globally many times over for people who never have access to such libraries. This policy will be a huge benefit to students and researchers at institutions without means, to independent scholars without easy access to academic libraries, to people with disabilities who struggle to access physical material, and to any reader who faces difficulties obtaining academic books.

More support for community-owned, open infrastructure for OA publishing will be a benefit for the publishing community as a whole. Projects such as COPIM will support an increase in capacity of OA book publishers (see Q66), creating a more diverse publishing landscape with greater capacity for equitably funded Open Access.

Ultimately, the open availability of more AHSS research will provide evidence of the necessity of these disciplines. An economic crisis is looming that will hurt universities particularly hard. We might see more AHSS courses threatened in the belief that these subjects are not economically worthwhile. But the reading figures for our books (see Q68) demonstrate that open AHSS research is read in great numbers all over the world. OA books could offer powerful evidence that research in the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences is necessary and worthy of support, and OA has the potential to create opportunities to build on that work in new ways.

Q61. Do you foresee UKRI’s proposed OA policy causing and/or contributing to any disadvantages or inequalities?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

If yes, please expand, referencing specific policy elements and including any comments on how UKRI could address any issues identified (2,650 characters maximum, approximately 400 words).

As explained in Q42 and 53, we are concerned that this policy should not entrench the BPC model of funding OA books, which replaces a barrier to read with a barrier to publish, and thus creates a whole new set of inequalities. We believe this would narrow participation in scholarly publishing, and be a misallocation of funds that could be spent in more effective ways, as argued in Q42 and 53.

We are also concerned that this problem might be exacerbated by a poor-quality Green OA system being widely used as a cheap alternative for those researchers who can’t afford a BPC, or for those publishers who don’t wish to develop an OA programme. This would create a two-tier system for OA work, in which those who can’t afford to pay lose out. See Q41, 42, 54 and 55 for more on this, including ways to improve the quality and discoverability of Green OA work. Finally, as mentioned in Q34, UKRI-funded PhD students could be disadvantaged if they are expected to publish work based on their thesis via an OA route without support in doing so. We believe the creation of a UKRI platform for its funded work would be a solution to this.

We would also like to follow Prof. Martin Eve’s lead here and rebut a common (and we believe, faulty) argument about OA and disadvantages.

- ‘This policy will disadvantage ECRs and academics seeking promotion.’ This argument disingenuously implies that academics themselves are not in control of the systems of career development and promotion. Further, the proposed REF mandate for OA books will greatly increase the number of authors publishing in this way, making it less of a ‘risky’ proposition. We would also suggest that the career of a scholar like Prof. Eve is itself a counterpoint to the claim that OA publishing damages an academic’s prospects.

- We also strongly echo Prof. Eve’s point that this argument about career prospects neglects the disadvantages that the present system confers on others, including people with disabilities – indeed all those whom we identified as potential beneficiaries of this OA policy in Q60.

Q62. Do you foresee any positive and/or negative implications of UKRI’s proposed OA policy for the research and innovation and scholarly communication sectors in low-and-middle-income countries?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

If yes, please expand, referencing specific policy elements and including any comments on how UKRI could address any issues identified (2,650 characters maximum, approximately 400 words).

Here we would like to echo the response of our colleagues in COPIM.

Benefits: increased open access to HSS and book research for scholars and the general public.

Drawbacks: If funding is provided for scholars in the UK to publish in OA by paying for BPCs, this will create further inequalities in access to publishing for scholars in the so-called Global South. This is why we are arguing for further investment in open infrastructure for books, and for the promotion of non-BPC business models for OA books.

We also caution against framing OA in terms of mere benefits for low- and middle-income countries, rather than an opportunity to learn from them. It is vital to recognise that countries outside the Global North have much to teach us for their approaches to open access monographs (see the Radical Open Access Collective for examples of this, https://radicaloa.postdigitalcultures.org/), particularly as many of these are funded by public money. This means that the UKRI policy poses both an opportunity and a threat to low- and middle-income countries in how it could either widen the gap between our approaches to knowledge creation or allow us to learn from their innovation here. We would encourage UKRI to invite Global South monograph publishers to discuss how the policy framework can learn from their expertise.

Q63. Do you anticipate any barriers or challenges (not identified in previous answers) to you, your organisation or your community practising and/or supporting OA in line with UKRI’s proposed policy?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

Q64. Are there any other supporting actions (not identified in previous answers) that you think UKRI could undertake to incentivise OA?

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

Yes / No / Don’t know / No opinion.

Yes / No.

If yes, please expand (2,650 characters maximum, approximately 400 words).

Here we would like to say a little more about the ‘scaling small’ model, which informs the thinking behind ScholarLed and COPIM (in which the ScholarLed presses, of which OBP is one, are key partners).

Despite the habitual focus on a small group of large legacy presses, there is huge diversity in the Arts and Humanities publishing landscape. Simon Tanner has noted that, for REF2014, 1,180 publishers were associated with the books submitted to Panel D (Arts and Humanities). Many of these were small and/or specialist presses, with the top ten publishers accounting for less than 50% of submissions.

We believe the scholarly ecosystem is best served by this diversity among publishers, producing a rich variety of books. The best way to ‘scale’ what OBP does is therefore not to grow bigger ourselves, but to facilitate OA publishing among multiple presses by developing the systems and infrastructures that will enable other publishers to produce Open Access books without needing to charge authors BPCs. In other words, we would be able to scale capacity while supporting smaller presses and projects, rather than relying on a small number of large organisations that can attempt to set the terms of scholarly publishing.

‘Scaling small’ has the potential to build capacity for OA book publishing in a significant way. The five not-for-profit, academic-led Open Access presses of ScholarLed (of which OBP is one) have between us published over 500 books, and expect to publish over 80 new titles in the coming year. Our collection is already the second-largest on OAPEN (see http://library.oapen.org/browse?type=collection).

We have been contacted by a number of small-to-medium-sized presses and publishing projects who are interested in ScholarLed and COPIM and how our work can help to develop and strengthen their own activities. What would the publishing landscape look like if, rather than 5 presses, ScholarLed was 25, 50, or 100 in number?

For more on ‘scaling small’, see Janneke Adema's presentation at the OpenAire 'Beyond APCs' workshop at the Hague on 5 April 2017, and ‘Bibliodiversity in Practice: Developing Community-Owned, Open Infrastructures to Unleash Open Access Publishing’ by Lucy Barnes and Rupert Gatti, ELPUB 2019 23rd edition of the International Conference on Electronic Publishing, Jun 2019, Marseille, France, www.doi.org/10.4000/proceedings.elpub.2019.21.

Yes / No.

Q68. Do you have any further thoughts and/or case studies on costs and/or benefits of OA?

Yes / No.

If yes, please expand (2,650 characters maximum, approximately 400 words).

Our metrics API, which allows access to all our book usage data, is open and available for anyone to use. Here you can access the usage data for all of our books, and see the amount these books are being used and shared (with the caveat that what we can measure will be only a subset of their actual use). For information about how to do this, see: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/section/84/1

Please find a list of successful, fully open access scholar-led book presses that have provided transparent information about their business models and costing structures here (as provided by our COPIM colleagues in their response, and highlighted again here):

Martin Eve, ‘How much does it cost to run a small scholarly publisher?’ (2017), https://www.martineve.com/2017/02/13/how-much-does-it-cost-to-run-a-small-scholarly-publisher/

Rupert Gatti, ‘Introducing Some Data to the Open Access Debate: OBP’s Business Model’ (2015), https://blogs.openbookpublishers.com/introducing-some-data-to-the-open-access-debate-obps-business-model-part-one/

Gary Hall, ‘Open Humanities Press: Funding and Organisation’ (2015), http://garyhall.squarespace.com/journal/2015/6/13/open-humanities-press-funding-and-organisation.html

Sebastian Nordhoff, ‘Calculating the costs of a community-driven publisher’ (2016), https://userblogs.fu-berlin.de/langsci-press/2016/04/18/calculating-the-costs-of-a-community-driven-publisher/

Sebastian Nordhoff, ‘What’s the cost of an open access book?’ (2015), https://userblogs.fu-berlin.de/langsci-press/2015/09/29/whats-the-cost-of-an-open-access-book