SO! Amplifies: Marginalized Sound—Radio for All

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome!

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome!Marginalized Sound is an online radio station that will launch in late 2020. The mission of the station is to provide a 24/7 platform for underrepresented sound artists to broadcast their work. Marginalized Sound will host music hours with varying genres, poetry readings, live event broadcasts, and special programs such as “Mental Health and the Artistic Process” (see audio sample below).

The station plans to interview coding musicians, poets, singer/songwriters, and composers from across the globe, as well as commission new works with pending grants. Sound art here is defined quite broadly and the station is very excited to uncover what this means to different people. For now, the breadth of work to be played includes sound plays from the 60s as well as contemporary, Congolese rap (see sample below).

Marginalized Sound will indulge a space outside of whiteness. By using the internet to broadcast to the globe, the station endeavors to reclaim space for underrepresented folk. J Diaz, founder, states, “What I’ve never understood is that diversity is a choice and as a society we continue to choose whiteness.” It is because of this that Marginalized Sound will unapologetically and enthusiastically support underrepresented people only (interested collaborators please click here for the form).

In the coming years, J Diaz hopes to turn this into a full-time job instead of just a hobby. He sees potential for the station to provide paid internships in audio and marketing, collaborations with local and international organizations or festivals, and collaborations with university courses.

The online station is raising funds to pay for initial filing fees to become a non-profit business. Please donate here: https://www.gofundme.com/f/ean89c-becoming-a-nonprofit. Other ways to help are to like the facebook page (www.facebook.com/marginalizedsound) and share it with three friends.

—

Featured image: logo for Marginalized Sounds

—

J Diaz is a Sound Artist currently based in Philadelphia, PA. He designs sound for a variety of mediums—including theatre, dance, and the concert stage. Over the past few years, J has collaborated on numerous projects with theatre and dance companies located across the continental United States and has even worked internationally. J holds a Bachelor of Musical Arts in piano from DePauw University (’13). He studied piano with Dr Phang and composition with Veronica Pejril and Dr Perkins. He holds an MFA in electroacoustic composition from the Vermont College of Fine Arts (’17) where he studied with Dr Mallia, Dr Early, and Dr Holland. In fall of 2018, J completed an MA in composition with distinction at The University of Sheffield under the supervision of Dr Ker.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

SO! Amplifies: Die Jim Crow Record Label

Deep Listening as Philogynoir: Playlists, Black Girl Idiom, and Love–Shakira Holt

My body, my traitor: essay in 10TAL

Last year Swedish magazine 10TAL published an essay of mine about data mining, the body, and self-knowledge. Now, the English translation has been published too! Read the opening below or click through to the whole text: My body, my traitor

We’ve come a long way, baby. From »On the internet nobody knows you’re a dog«, to »On the internet everybody knows I’m a top dog«, to »On the internet we’re all Pavlov’s dogs«. Or: from the homepage, to the social media identity, to the algorithmic profile. From the nerd, to the networked self, to the passive data goldmine (via the influencer).

This evolution can be read as a story of increasing corporality, as counterintuitive as that may seem. Usually, the story is told as if the world and its inhabitants are on their way to shedding all bodily weight, with the end-point on the horizon being a purely computerized humankind, all Mind and no Matter. But the inextricable entanglement of »online« and »offline«, »virtual« and »real«, primarily means that technology is all the time effecting the body (and thus, via the body, the soul). Like Pavlov’s dog, the post-digital condition is no »cloud« in which everything evaporates (and, as we know, what is called the cloud is a very material infrastructure that is using up as much energy as a small country, relying on cables that land on contested shores, demanding ever more precious metals to be mined from unstable regions). Rather, our bodies and the data that can be mined from them, function as the pathways to understanding, predicting and thus controlling or manipulating the world, which in the same gesture means understanding, predicting and thus controlling or manipulating the body, the very body that was mined in the first place.

In a catch-22 situation, you’re always made an accomplice to your own submission.

Continue reading over at 10TAL: My body, my traitor

Column – Take root among the stars: If Octavia Butler wrote design fiction

Authors: Gabriele Ferri, Inte Gloerich

“The Butler Timeline (BT) is a parallel universe where renowned speculative fiction author Octavia E. Butler engaged in a critical dialogue with researchers in human-computer interaction, shaping the genre of design fiction differently from how it unfolded in our timeline. Here we present a meta-speculation, imagining what could have been different if Butler, a prominent African American writer and intellectual, played a key role in establishing speculative design research. We do not want to create a temporal paradox but, if we had a transdimensional portal, we could simply observe how speculative research came to be in the BT. Hopefully, this could suggest another way of doing design fiction in our own reality, with a different ideology and purpose. That is why we volunteer for this interdimensional travel.”

Interactions XXVII.1 (January – February 2020)

Open peer review discussion

Thank you to Heather Staines from MIT’s Knowledge Futures Group for initiating this discussion in response to an invitation to participate in an open peer review process of the OA Main 2019 dataset and its documentation on the SCHOLCOMM list (the invitation was also sent to GOAL and the Radical Open Access List) and for permission to post her e-mails on Sustaining the Knowledge Commons.

Original e-mail (Heather Morrison to SCHOLCOMM, Jan. 7, 2020):

greetings,

** January 15 suggested deadline **

This is a reminder that open peer review is being sought for the Sustaining the Knowledge Common’s project OA main 2019 dataset and its documentation. For those who may not have time for a thorough peer review, a set of 6 questions is provided and responses to any of the questions would be welcome. This is an opportunity to participate in an experimental approach to two innovations in scholarly communication: a particular approach to open peer review, and peer review of a dataset and its documentation. The latter is considered important to encourage and reward researchers for data sharing.

Although full open peer review is the default, if anyone would like to remain anonymous this should be reasonably easy to accommodate by having a friend or colleague forward your comments with an indication of their anonymity.

January 15 is the deadline but if anyone interested would like to participate and needs more time, just let me know. Thank you to those who have already provided comments.

Details and materials can be found here:

best,

Dr. Heather Morrison

Associate Professor, School of Information Studies, University of Ottawa

Professeur Agrégé, École des Sciences de l’Information, Université d’Ottawa

Principal Investigator, Sustaining the Knowledge Commons, a SSHRC Insight Project

sustainingknowledgecommons.org

Heather.Morrison at uottawa.ca

https://uniweb.uottawa.ca/?lang=en#/members/706

[On research sabbatical July 1, 2019 – June 30, 2020]

Heather Staines, first response, Jan. 8, 2020:

Hi Heather:

I took a look at your open peer review survey. Very interesting!

I did a blog post during peer review week on collaborative community review. I thought you might find it interesting: https://thecommons.pubpub.org/pub/ek9zpak0/branch/1?access=fsivw788

[image omitted]

Collaborative Community Review on PubPub · The Knowledge Futures Commonplace

thecommons.pubpub.org

I interviewed the authors of three MIT Press books (coming 2020) who used open peer review on our open source platform, PubPub. If this would ever be helpful for you in pursuing future surveys or experiences, please do let me know.

Thanks,

Heather [Staines]

MIT Knowledge Futures Group

Heather Morrison response, Jan. 8, 2020:

Thank you, your blog post is very interesting.

I see tremendous potential for online collaborative writing and annotations. For example, last year I had students write crowdsourced online essays in class; students were asked to find one interesting recent article on privacy, prepare notes, and write a collaborative “current issues in privacy” in class. I have participated in online annotation peer review in the past.

However, I have some concerns about the annotation and collaborative writing approaches to peer review. My reasons, in case this is of interest:

An annotation approach, in my experience, invites and encourages wordsmithing and focus on minor issues and makes it difficult to contribute at a deeper level (e.g. issues of substance, critique of fundamental underlying ideas).

Depending on the project, individual, and group, the optimal approach might be collaborative writing or individual voice. In the area of open access and scholarly communication, I have a unique perspective and consider this my most important contribution. This gets lost in collaborative writing. For this reason, I write as an individual (or co-author as supervisor with students) in this area.

Although in the past I have participated in the online annotation approach to open peer review, I have been disappointed because my comments (well-thought-out comments by an expert in the field) have been ignored, not only dismissed but not even acknowledged in the final version. This is a waste of my time, and I argue that it is not appropriate to present a final version under such circumstances as having passed a peer review process. Also, in recent years I have noticed a tendency to require reviewers to agree to open licensing conditions that I have object to; this for me is sufficient reason not to participate. [A brief explanation of several key lines of argument on this topic can be found here].

One of my reasons and incentives for open peer review is to claim credit for this work; for example, this published peer review is an example of what I would like to gain from open peer review:

[Morrison, H. (2019). Peer review of Pubfair framework. Sustaining the Knowledge Commons. Retrieved from https://sustainingknowledgecommons.org/2019/09/24/peer-review-of-pubfair-framework/]

This is not for everyone, and I would not want to do this with every review, but occasional publication of such reviews opens up possibilities for study of the peer review process and allows me to appropriately claim my careful work in this area.

In the process of transforming scholarly communication I see fundamental questions about why we approach things the way we do, and how we might do things better, that I would like to see opened up for discussion. My blogpost / open invitation approach is deliberate; I consider development of platforms / checklist approaches as premature. This is developing technical solutions when, to me, we should be figuring out what the problems are.

This discussion should be part of the open peer review process. I am thinking of posting this response to my blog. May I post your e-mail as well?

best,

Dr. Heather Morrison

[signature]

Heather Staines, second response, Jan. 8, 2020:

Hi again:

Thank you for the quick and thoughtful response. Given some of your perspectives, you may also be interested in this companion piece, also from Peer Review Week, Making Peer Review More Transparent https://thecommons.pubpub.org/pub/kzujjdx8

I agree with you that there are challenges around an annotation-based approach. Prior to my role here at KFG, I was Head of Partnerships at Hypothesis (so I’m all about the annotation!). I continue to watch the evolution of annotation in the peer review space. Have you seen the Transparent Review in Preprints project: https://www.cshl.edu/transparent-review-in-preprints/?

I’m fine with your posting my previous (and current) emails, along with your responses. I hope we might cross paths sometime to discuss it further.

Thanks,

Heather [Staines]

[square brackets indicates minor changes from original e-mails]

The Queerness of Wham’s “Last Christmas”

Christmas pop songs tend to revolve around just a few basic topics: 1) Jesus, 2) Santa, 3) Did you notice it’s winter?, and 4) Love. These aren’t mutually exclusive categories, of course. For instance, the overlap between the second and fourth category produce a sub-genre I’d call Santa Kink, exemplified by “Santa Baby” and “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus.” And the overlap between the first and fourth categories—between Jesus songs and Love songs—is, I would argue, complete overlap. The dominance of Christian ideology in the United States means that even when Christmas pop songs don’t explicitly say anything about Christianity, they are reenforcing dominant Christian ideology all the same. That’s how hegemonies work: hegemonic ideas are always already implicit in a variety of discourses whether those discourses are closely or remotely related to that ideology. So while pop stars may shy away from Christmas songs about Jesus because they don’t want to seem too religious, any song with Christmas as its theme will inherently fold back onto Christian ideology regardless of an artist’s intentions.

So, what does it mean when Love and Jesus overlap in Christmas songs? It’s quintessentially heteronormative: a man, a woman, and a baby who will rescue humanity’s future. But hegemonies aren’t totalizing, so while they dominate discourse, it is possible to craft ontologies that map out other ways of being. Here, I’m going to engage the queerness of “Last Christmas”—the original Wham! version (1984)—and a 2008 Benny Bennasi remix of the original song. What each have in common is a failure to achieve heteronormativity that, in turn, undermines the Love/Jesus trope of Christmas pop songs; this failure orients us toward queer relationalities that plot alternatives to Christian heteronorms.

Looking back at those four categories of Christmas pop songs, three of them make lots of sense for a Christmas song topic: Jesus, Santa, and winter. But why love? In part, it’s because most pop music boils down to love in some way. Beyond that, though, a love song in the context of Christian heteronormative ideology yields what Lee Edelman calls “reproductive futurity”:

terms that impose an ideological limit on political discourse as such, preserving in the process the absolute privilege of heteronormativity by rendering unthinkable, by casting outside the political domain, the possibility of a queer resistance to this organizing principle of communal relations.

In other words, the heteronormative imperative of reproducing and then protecting (white) Children is embedded so deeply in politics that it isn’t even up for debate. It is, instead, the societal framework within which debate happens, and anything outside that framework resonates as queer.

Pivoting back to Christmas, it’s instructive to contemplate the nativity scene. It can be built with a variety of details, but at its center every time is Jesus, Mary, and Joseph—baby, mom, and dad. In a reproductive futurist society, recurring images like the nativity scene underscore the normalcy of the nuclear family, regardless of how utterly abnormal the details of the story surrounding the nativity scene might be. The heteronormativity of the nativity scene “impose[s] an ideological limit” on the discourse of Christmas love songs: every cuddle next to the fireplace, each spark under the mistletoe, all coercive “Baby, it’s cold outside”s are a reproduction of the christian Holy Family (baby, mom, and dad). What on the surface is simply Mariah Carey’s confession that all she wants for Christmas is you becomes miraculously pregnant with a dominant religio-political ideology that delimits queerness and manufactures White Children. That’s why pop stars sing Christmas love songs when they don’t want to sing about Jesus or Santa or winter; it’s because the love songs buttress a Christian ideology that squares comfortably with dominant political discourse even when they don’t explicitly mention religion.

The texture of my “Last Christmas” analysis is woven from a few theoretical strands. Jack Halberstam’s queer failure and Sara Ahmed’s queer phenomonology each orient us to queer relationalities that emerge from getting heteronormativity wrong. Hortense Spillers’ vestibular flesh and Jayna Brown’s utopian impulses tune us to the vibrations of alterity buzzing just beyond hegemony’s earshot. Taken together, these theories open space for hearing how a Christmas pop song about love might resonate queerly even in the midst of heteronormative dominance. Instead of rehearsing the nativity scene, a queer Christmas pop song might undo, sidestep, detonate, or otherwise fail to recreate the nativity. A queer analysis of Christmas pop songs looks and listens for moments of potential disruption in the norm.

Screenshot from official video from “Last Christmas”

In a reproductive futurist world, Wham!’s “Last Christmas” is a nightmare: heartbreak, disillusionment, and loneliness. Lyrically, the hook tells us that this year our singer has found someone special, but the verses betray the truth: he’s still hung up on last year’s heartbreak and has already started hoping that, actually, maybe next year will be the one that works out for him. I think we can push deeper than this lyrical message of hope (strained though it is) and find something a little Scroogier in the structure of the song, a denial of fulfilled desire that projects a queer, non-reproductive future:

Intro (8 measures) (0:00)

Chorus (16 measures) (0:15)

Post-Chorus (8 measures) (0:53)

Verse 1 (16 measures) (1:11)

Chorus (1:47)

Post-Chorus (2:23)

Verse 2 (2:41)

Chorus (3:17)

Post-Chorus (with partial lyrics from Verse 2) (3:53)

Post-Chorus (4:11)

There’s a reason we all know the chorus so well: it’s a double chorus that happens three times. That is, from “Last Christmas” to “someone special” is only 8 measures long, but that quatrain is repeated twice for a 16 measure chorus. So that’s six different times we hear George Michael summarize what happened last Christmas, and it becomes easy to recognize that this is less a celebration of having someone special than it is an attempt to convince oneself of something that isn’t true. When we compound the double chorus with the percussion part, which hits a syncopated turnaround every four measures (the turnaround signifies moving on to a new part; by repeating the same one every four measures in the middle of lyrical monotony, the song suggests a failure to really move on), the effect is one of extreme repetition. We rehearse, over and again, the failure of last Christmas, the failure to hetero-love, the failure to reproduce anything but, well, failure.

What I’ve labeled the Post-Chorus is a bit of an oddity here, a musical interlude played on festive bells that separates Chorus from Verse. The work it performs is best understood in conjunction with the music video. In the video, a group of friends meet to enjoy a getaway at a ski lodge; the character played by George Michael is here with this year’s girlfriend, and last Christmas’s girlfriend brings this year’s boyfriend. Intrigue! The visual narrative matches the song. In the same way the jolly instrumental seems largely unaware of Michael’s downer lyrics, the group of friends seem oblivious to the furtive, hurt glances between last Christmas’s lovers. This structural oddity, the Post-Chorus, proves key to the visual narrative. There’s a Scrooge in this story, and the Post-Chorus will visit him in the night.

The first Post-Chorus is the ghost of Christmas present. As the friends crowd into a ski lift that will take them to their lodging, the first bell hits right as last year’s girlfriend is center screen (0:53 in the video above), and we watch as the friends arrive at their getaway, the final two measures playing over a wide-angle shot of a ridiculously large cabin. The second Post-Chorus is the ghost of Christmas past. Here, as everyone gathers around a feast, all holly and jolly, the bells (2:23) strike at the moment Michael catches sight of the brooch he gave last Christmas’s girlfriend. He broods. The payoff comes in the second half of Verse 2 (2:59), when we see a flashback to the happy couple the year before, when they frolicked in the snow, lounged by the fire, and exchanged fabulous 80s jewelry. Finally, the third Post-Chorus is the ghost of Christmas future. This time the bells strike as the group is hiking back to the ski lift, returning to the point where they began. We hear the Post-Chorus twice this time, and the first instance (3:53) is accompanied by lyrics pulled from the flashback section of Verse 2, where Michael describes himself and the heartless way he’s been treated. This time, though, instead of finishing the line with “now I’ve found a real love, you’ll never fool me again,” Michael can only offer a breathy “maybe…next year.” In this third Post-Chorus, we have future (maybe next year) overlapping with past (the flashback lyrics) accompanied by visuals that close the narrative circle – a return on the same ski lift we see during the first Post-Chorus. In other words, Michael’s character can sing about someone special all he wants, but the song knows last year’s failure to reproduce will repeat again and again. The fourth Post-Chorus hammers this repetition home: as the friends debark from the lift and the screen fades, we hear this Christmas ghost haunting, lingering at the edges, reproducing heteronormative failure ad infinitum (the fade in the music suggests there’s no definitive ending point).

Screenshot from Wham’s “Last Christmas”

George Michael, of course, was publicly closeted for a long time. It’s unsurprising that we see some horror motifs in this heterofest. The wide-angle shot of the isolated cabin, the close up of a brooding, tortured hero…There may well be a queerness in the absence of gendered pronouns and in the visual aesthetic of the music video. But the real disruption, I think, comes in the structural repetition, the rehearsal of the singer’s failure to reproduce each year at the moment that reproduction is most central. If Christmas love songs circulate in a framework of reproductive futurity, “Last Christmas” Scrooges its way onto the airwaves every year and projects an utter failure of a future.

Most Christmas pop songs come and go. The drive to fill the airwaves with a genre of music that is only functional for 6-8 weeks of the year yields heaps of treacly sonic detritus. Christmas pop songs are, by nature, ephemeral. A few of these songs, though, become classics that artists return to and cover or remix over and again. “Last Christmas” is one of these classics, settling onto November and December playlists in its original form and the myriad cover versions that have piled up over the years. Benny Benassi’s “Last Christmas” remixes the Wham! song in a way that maintains the original’s queerness even as it flips the idea of looping failures.

Benassi’s “Last Christmas” revolves around two main sections: a driving techno beat (A) and a reworking of Wham!’s chorus (B).

A (48 measures)

B (48 measures) (1:25)

A’ (24 measures) (2:22)

B’ (56 measures) (3:04)

A” (32 measures) (4:15)

The A sections include a voiceover from a computerized voice affected so that it sounds like some dystopic transmission. “We would like to know if something does not sound quite right,” the voice starts, and then preps the entry of section B with “to guarantee safety to your perfect celebration, be sure – when playing this tune at maximum volume level – to chant around like everybody else is.” It’s hard to be more on-the-nose than this: an android voice instructing us how to fit in at our reproductive futurist holiday gatherings. “You know, just…I don’t know, just do what the others are doing?”

The B sections are each a sequence of three “Last Christmas” choruses (B’ includes an extra eight measures of the third in the sequence). The first is a sped-up but otherwise unaltered Michael singing about last Christmas. It’s a jarring entry, as the cool machinery of Benassi’s beat suddenly gives way to shimmery 80s pop. The second time through that familiar double chorus, we can hear Benassi’s groove faintly in the background and growing louder and fuller toward the end. It’s a straightforward remix technique: here’s the thing, here’s the thing mixed with my beat, and now here’s what I’m really getting at.

It’s the third sequence (1:53), then, where Benassi really crafts his own “Last Christmas.” Here, the beat we heard when the android told us how to fit in combines with Michael’s chorus as Benassi stutters and clips not only the lyrics but the instrumental, too: nothing is stable. Michael can’t finish a sentence (“La-a-as-a-ast, I gave you my gave you my hear-. Thiii-i-i-i-is year to save me from save me from, I’ll give it to someone, I’ll give it to someo-o-one.”), and the beat can’t get a firm start. While Wham!’s “Last Christmas” uses the Post-Chorus to form a closed loop where past and future circle back around to each other, Benassi’s “Last Christmas” denies reproductive futurity by chopping off the beginnings and ends of phrases. Built on a simple two-measure loop that otherwise motors smoothly through the song, Benassi’s “Last Christmas” can’t loop in the third sequence of the B section because there’s nothing to latch onto.

While Wham! loops queer failures in their overarching forms, Benassi’s version of the song queerly fails to loop. Both versions of “Last Christmas” bah and humbug at reproductive futurism. They’re Scroogey reminders each year to listen for disruptions of nativity, refusals of politically delimited desires that are queerly vibrating through our earbuds.

_

Featured image: “GOOD BYE and THANK YOU” by Flickr user fernando butcher, CC BY 2.0

_

Justin aDams Burton is Assistant Professor of Music at Rider University. His research revolves around critical race and gender theory in hip hop and pop, and his book, Posthuman Rap, is available now. He is also co-editing the forthcoming (2018) Oxford Handbook of Hip Hop Music Studies. You can catch him at justindburton.com and on Twitter @j_adams_burton. His favorite rapper is one or two of the Fat Boys.

_

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Benefit Concerts and the Sound of Self-Care in Pop Music–Justin Adams Burton

Audio Culture Studies: Scaffolding a Sequence of Assignments– Jentery Sayers

“Hearing Queerly: NBC’s ‘The Voice’”– Karen Tongson

Out Now: Deep Pockets #3 Scenes of Independence: Cultural Ruptures in Zagreb (1991-2019)

By Sepp Eckenhaussen.

After the violent disintegration of Yugoslavia, a flourishing cultural scene was established in Croatia’s capital Zagreb. The scene calls itself: independent culture. In this book, Sepp Eckenhaussen explores the history of Zagreb’s independent culture through three questions: How were independent cultures born? To whom do they belong? And what is the independence in independent culture? The result is a genealogy, a personal travel log, a mapping of cores of criticality, a search for futurologies, and a theory of the scene.

Once again, it turns out that localist perspectives have become urgent to culture. The untranslatability of the local term ‘independent culture’ makes it hard for the outsider to get a thorough understanding of it. But it also makes the term into a crystal of significance and a catalyst of meaning-making towards a theory of independent culture.

Author: Sepp Eckenhaussen

Foreword: Leonida Kovač

Editing: Miriam Rasch and Rosie Underwood

Cover design: Laura Mrkša

Published by the Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, 2019.

ISBN: 978-94-92302-40-3

This publication is licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerrivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Get the book:

Order a print copy here.

Download PDF here.

Download ePub here.

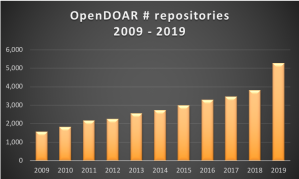

Dramatic Growth of Open Access 2019

201 9 was another great year for open access! Of the 57 macro-level global OA indicators included in The Dramatic Growth of Open Access, 50 (88%) have growth rates that are higher than the long-term trend of background growth of scholarly journals an d articles of 3 – 3.5% (Price, 1963; Mabe & Amin, 2001). More than half had growth rates of 10% or more, approximately triple the background growth rate, and 13 (nearly a quarter) had growth rates of over 20%.

9 was another great year for open access! Of the 57 macro-level global OA indicators included in The Dramatic Growth of Open Access, 50 (88%) have growth rates that are higher than the long-term trend of background growth of scholarly journals an d articles of 3 – 3.5% (Price, 1963; Mabe & Amin, 2001). More than half had growth rates of 10% or more, approximately triple the background growth rate, and 13 (nearly a quarter) had growth rates of over 20%.

Newer services have an advantage when growth rates are measured by percentage, and this is reflected in the over 20% 2019 growth category. The number of books in the Directory of Open Access Books tops the growth chart by nearly doubling (98% growth); bioRxiv follows with 74% growth. A few services showed remarkable growth on top of already substantial numbers. As usual, Internet Archive stands out with a 68% increase in audio recordings, a 58% increase inco

Newer services have an advantage when growth rates are measured by percentage, and this is reflected in the over 20% 2019 growth category. The number of books in the Directory of Open Access Books tops the growth chart by nearly doubling (98% growth); bioRxiv follows with 74% growth. A few services showed remarkable growth on top of already substantial numbers. As usual, Internet Archive stands out with a 68% increase in audio recordings, a 58% increase inco llections, and a 48% increase in software. The number of articles searchable through DOAJ grew by over 900,000 in 2019 (25% growth). OpenDOAR is taking off in Asia, the Americas, Africa, and overall, with more than 20% growth in each of these categories, and SCOAP3 also grew by more than 20%.

llections, and a 48% increase in software. The number of articles searchable through DOAJ grew by over 900,000 in 2019 (25% growth). OpenDOAR is taking off in Asia, the Americas, Africa, and overall, with more than 20% growth in each of these categories, and SCOAP3 also grew by more than 20%.

The only area indicating some cause for concern is PubMedCentral. Although overall growth of free full-text from PubMed is robust. A keyword search for “cancer” yields about 7% – 10% more free full-text than a year ago. However, there was a slight decrease in the number of journals contributing to PMC with “all articles open access”, a drop of 138 journals or a 9% decrease. I have double-checked and the 2018 and 2019 PMC journal lists have been posted in the dataverse in case anyone else would like to check (method: sort the “deposit status” column and delete all Predecessor and No New Content journals, then sort the “Open Access” column and count the number of journals that say “All”. The number of journals submitting NIH portfolio articles only grew by only 1. Could this be backtracking on the part of publishers or perhaps technical work underway at NIH?

Full data is available in excel and csv format from: Morrison, Heather, 2020, “Dramatic Growth of Open Access Dec. 31, 2019”, https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/CHLOKU, Scholars Portal Dataverse, V1

References

Price, D. J. de S. (1963). Little science, big science. New York: Columbia University Press.

Mabe, M., & Amin, M. (2001). Growth dynamics of scholarly and scientific journals. Scientometrics, 51(1), 147–162.

This post is part of the Dramatic Growth of Open Access Series. It is cross-posted from The Imaginary Journal of Poetic Economics.

Cite as:

Out Now: TOD#32 Networked Content Analysis: The Case of Climate Change

TOD#32: Networked Content Analysis: The Case of Climate Change

By Sabine Niederer

With a foreword by Klaus Krippendorff

Description:

Climate change is one of the key societal challenges of our times, and its debate takes place across scientific disciplines and into the public realm, traversing platforms, sources, and fields of study. The analysis of such mediated debates has a strong tradition, which started in communication science and has since then been applied across a wide range of academic disciplines.

So-called ‘content analysis’ provides a means to study (mass) media content in many media shapes and formats to retrieve signs of the zeitgeist, such as cultural phenomena, representation of certain groups, and the resonance of political viewpoints. In the era of big data and digital culture, in which websites and social media platforms produce massive amounts of content and network this through hyperlinks and social media buttons, content analysis needs to become adaptive to the many ways in which digital platforms and engines handle content.

This book introduces Networked Content Analysis as a digital research approach, which offers ways forward for students and researchers who want to work with digital methods and tools to study online content. Besides providing a thorough theoretical framework, the book demonstrates new tools and methods for research through case studies that study the climate change debate with search engines, Twitter, and the encyclopedia project of Wikipedia.

Colophon:

Author: Sabine Niederer

Foreword: Klaus Krippendorff

Editing: Rachel O’Reilly

Visualizations: Carlo de Gaetano

Production: Sepp Eckenhaussen

Cover design: Katja van Stiphout

Supported by the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Faculty of Digital Media and Creative Industries.

Published by the Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, 2019.

ISBN: 978-94-92302-42-7

This publication is licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerrivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Get the book:

Order a print copy here.

Download PDF here.

Download ePub here.

Annual Report 2019

As we come to the end of this year, it is with great pride that we look back at the many exciting things that have happened here at OBP in 2019!

From great new open access titles like Conservation Biology in Sub-Saharan Africa and Non-Communicable Disease Prevention, innovative publications like Annunciations: Sacred Music for the Twenty-First Century or Image, Knife, and Gluepot: Early Assemblage in Manuscript and Print to prize-winning books, new series and exciting projects, this has been a remarkable year for us.

As you prepare to celebrate the holiday season, don’t miss out on our last 2019 newsletter to find out more about all our achievements, future plans and interesting news!

New Open Access Publications in 2019

This year we have published a total of 30 books, which exceeds any previous year! We have not only released fantastic new titles both from first-time and returning authors but also four new textbooks and a number of enhanced editions of previously published books.

2019 opened with the publication of Life Histories of Etnos Theory in Russia and Beyond and of Delivering on the Promise of Democracy. Returning author George Corbett edited Annunciations: Sacred Music for the Twenty-First Century a collection of essays interrogating the theme of annunciations through music, which includes embedded recordings and sheet music of new choral pieces written as part of the research for the book; Image, Knife, and Gluepot: Early Assemblage in Manuscript and Print by Kathryn M. Rudy is a valuable text for any scholar in the fields of medieval studies, the history of early books and publishing, cultural history or material culture; Essays on Paula Rego by Maria Manuel Lisboa is an important collection of writings on one of the leading artists of our time.

We have added two new titles to our OBP Series in Mathematics: the second edition of Advanced Problems in Mathematics: Preparing for University by Stephen Siklos and The Essence of Mathematics Through Elementary Problems by Alexandre Borovik and Tony Gardiner, a textbook that consists of a sequence of 270 problems with commentary and full solutions. There have also been new additions to our OBP Classics Series from the pen of Flora Kimmich, who skilfully translated Schillers' Kabale und Liebe, and by Howard Gaskill, who has translated Hölderlin’s only novel, Hyperion.

New and very innovative titles on history, biology, linguistics and sociology approached from a non-European perspective hit the press this year! The Politics of Language Contact in the Himalaya edited by Selma K. Sonntag and Mark Turin offered readers a nuanced insight into language and its relation to power in this geopolitically complex region; History of International Relations: A Non-European Perspective by Erik Ringmar pioneered a new approach by explicitly focusing on non-European cases, debates and issues. Finally, Conservation Biology in Sub-Saharan Africa by John W. Wilson and Richard B. Primack - the first OA conservation biology textbook for Africa - has proved an essential resource for students, as well as a handy guide for professionals working to stop the rapid loss of biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere.

This year we have also successfully published a wealth of books by many more authors, both new and returning: R. H. Winnick's Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels, Rosella Mamoli Zorzi and Katherine Manthorne's From Darkness to Light: Writers in Museums 1798-1898, Janis Jefferies and Sarah Kember's Whose Book is it Anyway? A View From Elsewhere on Publishing, Copyright and Creativity, Deborah Willis, Ellyn Toscano and Kalia Brooks Nelson's Women and Migration: Responses in Art and History, Chris Rowell's Social Media in Higher Education: Case Studies, Reflections and Analysis, The Pogroms in Ukraine, 1918-19: Prelude to the Holocaust by Nokhem Shtif, translated by Maurice Wolfthal, Make We Merry More and Less: An Anthology of Medieval English Popular Literature, edited by Douglas Gray and Jane Bliss, Infrastructure Investment in Indonesia: A Focus on Ports, edited by Colin Duffield, Felix Kin Peng Hui and Sally Wilson, Ernesto Screpanti's Labour and Value: Rethinking Marx’s Theory of Exploitation, Engaging Researchers with Data Management: The Cookbook and Joachim Otto Habeck's Lifestyle in Siberia and the Russian North. Finally, the 2019 edition of What Works in Conservation came out this summer and has since then been read more than 1500 times!

We are closing 2019 with three exciting hot-off-the-press titles: Non-Communicable Disease Prevention: Best Buys, Wasted Buys and Contestable Buys, a book commissioned by the Prince Mahidol Award Conference (PMAC), an annual international conference centered on policy of global significance related to public health and written for the benefit of the global health community; Prose Fiction: An Introduction to the Semiotics of Narrative, a textbook that equips its readers with the necessary tools to embark on further study of literature, literary theory and creative writing; and The DARPA Model for Transformative Technologies: Perspectives on the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, a remarkable collection of leading academic research on DARPA from a wide range of perspectives, combining to chart an important story from the Agency’s founding in the wake of Sputnik, to the current attempts to adapt it to use by other federal agencies.

We would like to thank our authors for their extraordinary work and our readers for their continued support!

Our 2019 Open Access Series

In 2019, we have announced a number of new series all of which are open for proposals, so feel free to get in touch if you or someone you know is interested in submitting a manuscript!

The St Andrews Studies in French History and Culture Series, previously published by the Centre for French History and Culture at the University of St Andrews, aims to enhance scholarly understanding of the historical culture of the French-speaking world and it covers the full span of historical themes relating to France: from political history, through military/naval, diplomatic, religious, social, financial, cultural and intellectual history, art and architectural history, to literary culture.

We relaunched our 2018 series Applied Theatre Praxis (ATP) which focuses on Applied Theatre practitioner-researchers who use their rehearsal rooms as "labs”; spaces in which theories are generated, explored and/or experimented with before being implemented in contentious and/or vulnerable contexts. ATP invites writing that draws from the author’s praxis to generate theory for diverse manifestations of Applied Theatre. We would like to take this opportunity to welcome Natasha Oxley, our new member of the ATP editorial board!

We will soon be launching the first title of our Cambridge Semitic Language and Cultures series created in collaboration with the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge. This series includes philological and linguistic studies of Semitic languages and editions of Semitic texts. Titles in the series will cover all periods, traditions and methodological approaches to the field.

Finally, we are also welcoming chapter proposals for the book What Do We Care About? A Cross-Cultural Textbook for Undergraduate Students of Philosophical Ethics. This book is a bold attempt to provide a comprehensive and broad perspective on ethics to undergraduate students by incorporating a non-Eurocentric, non-biased way of presenting traditions from Asia, Africa, North-America, South-America, Australia and Europe. If you'd like to submit a proposal and/or find out more about the submission process for this title, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/section/114/1.

For other inquiries regarding these series, you can contact our director Dr Alessandra Tosi here.

Our Award-Winning Open Access Titles

In 2019, some of our books have been recognised with prizes for the quality of their scholarship and the innovation of their presentation:

Literature Against Criticism: University English and Contemporary Fiction in Conflict by Martin Paul Eve

Martin Eve was awarded the prestigious Philip Leverhulme Prize in 2019, and we are particularly proud that Literature Against Criticism formed a substantial part of his submission portfolio for the award. The Philip Leverhulme Prize recognises the achievement of outstanding researchers at an early stage of their careers, whose work has already attracted international recognition and whose future career is exceptionally promising. We are delighted that Martin and Literature Against Criticism have been recognised in this way.

A Fleet Street in Every Town: The Provincial Press in England, 1855-1900 by Andrew Hobbs

Winner of the 2019 Robert and Vineta Colby Scholarly Book Prize for best book on Victorian newspapers and periodicals – awarded annually by the Research Society for Victorian Periodicals.

The selection committee described the book as 'field-defining'; a title that 'convincingly challenges enduring assumptions that London newspapers acted as the national press in the Victorian period.' They exalted its 'meticulous research, originality, and significance for future scholars' of the provincial press in Britain, whilst also noting that it is 'written with imagination, flair and infectious enthusiasm', bringing 'the nineteenth century press to full, vibrant, pulsating life'.

The Jewish Unions in America: Pages of History and Memories by Bernard Weinstein, translated and annotated by Maurice Wolfthal

Winner of the 2018 Choice Review's Outstanding Academic Title.

Every year in the January issue, in print and online, Choice publishes a list of Outstanding Academic Titles that were reviewed during the previous calendar year. This prestigious list reflects the best in scholarly titles reviewed by Choice and brings with it the extraordinary recognition of the academic library community. Wolfthal's excellent title has been awarded for its overall excellence in presentation and scholarship, its importance within the field, its value to graduate students and its uniqueness of treatment.

Congratulations to the winners!

OBP: A Top Social Enterprise

2019 has not only been a successful year for our authors but also for us since we made it to the Top 100 of the NatWest SE100 Index 2019!

This award celebrates the growth, impact and resilience of social ventures in the UK by recognising the most impressive 100 social enterprises of the year.

You can read more about this here.

Community-led Open Publication Infrastructures for Monographs

On 14th June this year, Research England announced the award of a £2.2 million grant to the Community-led Open Publication Infrastructures for Monographs (COPIM) project, which is designed to build much-needed community-controlled, open systems and infrastructures that will develop and strengthen open access book publishing. This was followed in October by the announcement of an £800,000 grant from the Arcadia fund. Open Book Publishers is a key partner in the COPIM project, with our fellow ScholarLed presses and leading universities, libraries and infrastructure providers from the UK and around the world. COPIM will transform open access book publishing by moving away from a model of competing commercial service operations to a more horizontal and cooperative, knowledge-sharing approach.

Read more about this promising project in Lucy Barnes’s blog post and in this announcement by ScholarLed.

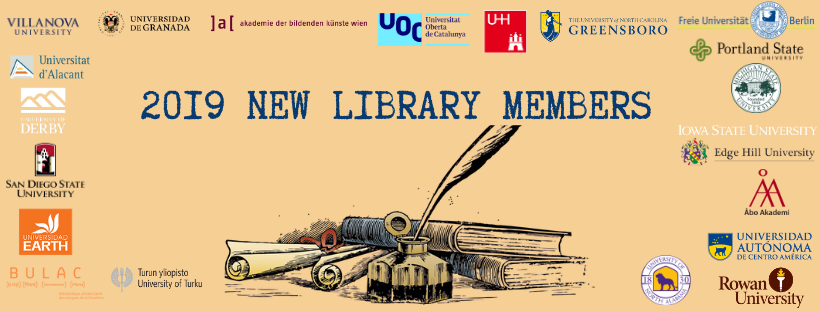

New Library Members 2019

We wholeheartedly thank all the universities that have joined our membership programme in 2019 and who have decided to help us in providing academic monographs that can be read for free worldwide. The support we receive from libraries is vital to help us continue our work!

These are the libraries that joined our membership scheme in 2019:

Villanova University - United States

Earth University - Costa Rica

Universitat Oberta de Catalunya - Spain

Universidad Autónoma de Centro América - Costa Rica

Universidad de Granada - Spain

Universitat D'Alacant - Spain

University of North Alabama - United States

Universität Hamburg - Germany

Åbo Akademi University Library - Finland

Portland State University Library - United States

University of North Carolina Greensboro - United States

San Diego State University Library - United States

Edge Hill - United Kingdom

University of Derby - United Kingdom

Iowa State University Library - United States

Michigan State University - United States

Academy of Fine Arts Vienna - Austria

BULAC (Bibliothèque universitaire des langues et civilisations) - France

Freie Universität Berlin - Germany

Turku University Library - Finland

Rowan University Libraries - United States

If you'd like to find out more about the benefits of membership for staff & students, visit http://bit.ly/2mXOfJY

OBP Global Statistics 2019

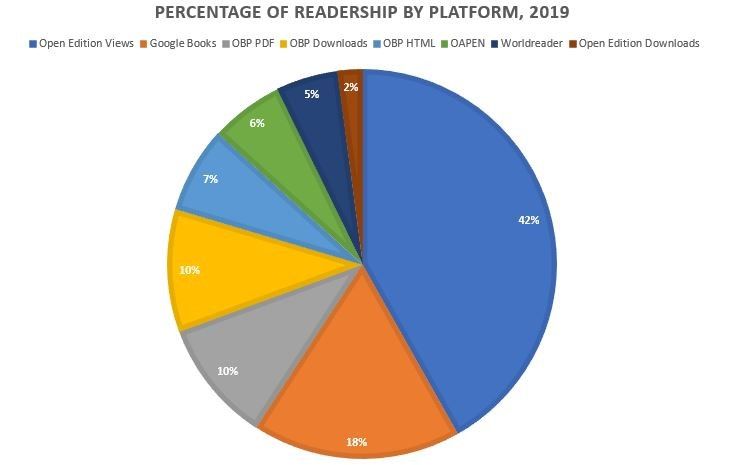

As Open Access works, our titles are available on a multitude of different platforms, and readers have multiple means of accessing them. Collecting and collating usage statistics for our books is challenging, and clearly any data reported will be at the lower end of ‘true’ usage, as we are unable to obtain data from all platforms.

During the year, we have collected book level usage data from the following sources: OBP’s Free Online PDF Reader; OBP’s Free HTML Reader; free ebook downloads from OBP; Google Play; and visitors to our titles hosted on Google Books, OpenEdition, WorldReader, OAPEN and the Classics Library. We are pleased to have introduced on our website detailed readership reports across these platforms at the level of individual titles. To find out more about the data we have been collecting, please visit our page on how we collect our readership statistics and if you'd like to know more about what we mean by usage data, you can read Lucy Barnes' latest blog post What We Talk About When We Talk About… Book Usage Data.

Our Global Reach

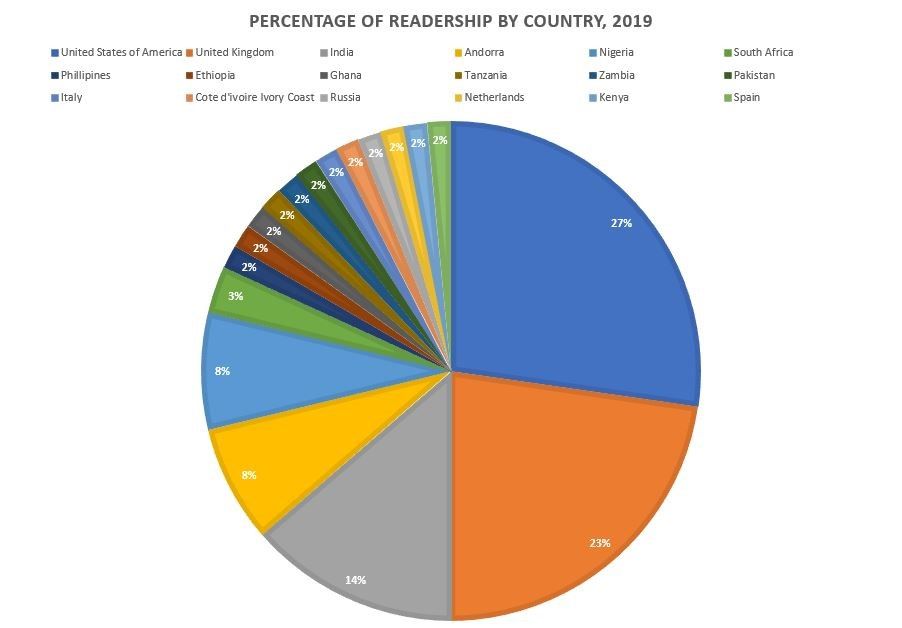

This year we welcomed readers from 219 different countries and states confirming that our titles have worldwide reach. The United States, United Kingdom, India, Nigeria and South Africa are the top 5, followed by the Phillippines, Ethiopia, Ghana, Tanzania, Zambia and Pakistan. We look forward to having an even bigger global impact in the years ahead.

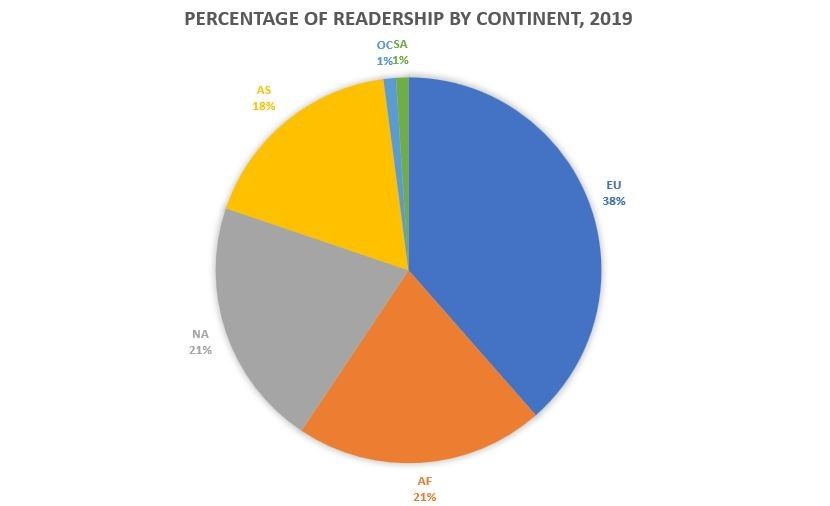

In our percentage of readership by continent, Europe is in first place with 38% of our total readership, followed by Africa and North America with 21% each and Asia with 18%.

We would like to thank our readers for engaging with our books this year!

New-Look Blog

All things must come to an end...and be replaced with something better!

This last month we have launched our new blog with a new and more user-friendly design where you can find all our previous posts, including posts this year on metrics, Open Access academic publishing, English and German Literature, international relations and language politics that we'd like to invite you to read!

To check out our new blog and all our new content, visit https://blogs.openbookpublishers.com/.

OBP to Shrink our Carbon Footprint in 2020

In the forthcoming year we will publish a number of books about climate change, its impact on our world and the importance of sustainability – these include Earth 2020: An Insider’s Guide to a Rapidly Changing Planet (ed. Philippe D. Tortell); Living Earth Community: Multiple Ways of Being and Knowing (eds. Sam Mickey, Mary Evelyn Tucker, and John Grim) and What Works in Conservation 2020 (eds. William J. Sutherland, Lynn V. Dicks, Nancy Ockendon, Silviu O. Petrovan and Rebecca K. Smith).

Inspired by the work of our authors, next year we will be taking steps to shrink our carbon footprint and we will be blogging about it along the way, so keep an eye on our blog to find out more about what we learn and all we achieve throughout 2020!

Thanks to Our Volunteers!

At OBP, we offer direct training placements in all aspects of Open Access publishing, free of charge. We provide placements to individuals, as part of university courses such as the MSt in Creative Writing at the University of Oxford, and to other Open Access publishers such as UGA Editions and Firenze University Press. However, we also welcome volunteers of different levels of skill and experience who want to work with us either at our Cambridge office or remotely.

This year we have had the pleasure of working along some great volunteers and we would like to take this opportunity to thank them for all their help and hard work - we strongly appreciated their support and assistance!

Elena Prat

Naveed Ashraf

Maddie Janjo

Annalena Lorenz

Robert Wilding

Theodore Martin

Natalie Ansell

Claudia Griffiths

Ryan Norman

Julie Linden

Elizabeth Lowe

Edwin Rosta

Ammara Naveed

If you or someone you know would like to have the opportunity to try a range of key publishing aspects, including marketing, editorial and text-formatting tasks in a non-corporate environment, please contact Alessandra Tosi.

We Want to Hear from You!

We are very grateful for the support our member libraries give us, and we are keen to find out what more we could be doing in return. For this reason, we would like to invite you to take part in a short survey which will provide an opportunity for us to find out more about what you would like us to be doing for you. Your participation in this survey is completely voluntary and all of your responses are anonymous.

If you have any questions about this survey, or difficulty in accessing the site or completing the survey, please contact laura@openbookpublishers.com.

We would love to hear from all our librarians and know more about the ways they think we can improve!

And finally...

May the holiday season end the present year on a cheerful note and make way for a fresh and bright New Year!