Daniël de Zeeuw PhD Ceremony: Between Mass and Mask-The Profane Media Logic of Anonymous Imageboard Culture

On 18 December 2019 Daniël de Zeeuw will defend his dissertation before a committee of learned colleagues at the University of Amsterdam. He happily invites all of you to attend the ceremony.

Time: 11.45 Doors open (ceremony starts at 12.00 sharp), 13.00 Reception.

Location: Agnietenkapel, Oudezijds Voorburgwal 229 – 231, 1012 EZ Amsterdam (NL).

For questions, please contact the paranymphs Patricia de Vries and Helmer Stoel via promotiedaniel2019@gmail.com.

—

Between Mass and Mask: The Profane Media Logic of Anonymous Imageboard Culture by Daniël de Zeeuw

This study analyzes the online “mask culture” of image boards like 4chan in opposition to the dominant “face culture” of social media platforms like Facebook. It is argued that whereas the latter casts the user as possessing a clearly delineated and persistent personal identity, the former fosters a paradoxical sense of (non)identity that is ephemeral and im-personal, and that forms a monstrous and grotesque media body, in which the boundaries of the self are rendered porous by way of a festive immersion in digital dirt and anonymous contact. In this, it is shown, mask culture radically embodies the profane media logic that inheres in contemporary culture as a whole. The study seeks to understand this logic with an eye to its emancipatory potentials as well as its more problematic aspects, by situating it in the larger historical and aesthetic lineages of modern mass (media) culture and the carnivalesque tradition in popular culture and art. What this reveals is an affinity between mass and mask that, albeit precariously, continues to resonate in the present.

My Voice, or On Not Staying Quiet

Welcome to Next Gen sound studies! In the month of November, you will be treated to the future. . . today! In this series, we will share excellent work from undergraduates, along with the pedagogy that inspired them. You’ll read voice biographies, check out blog assignments, listen to podcasts, and read detailed histories that will inspire and invigorate. Bet. –JS

Welcome to Next Gen sound studies! In the month of November, you will be treated to the future. . . today! In this series, we will share excellent work from undergraduates, along with the pedagogy that inspired them. You’ll read voice biographies, check out blog assignments, listen to podcasts, and read detailed histories that will inspire and invigorate. Bet. –JS

Today’s post comes from Binghamton University sophomore Kaitlyn Liu, former SO! intern and student in SO! Editor-in-Chief J. Stoever’s English 380W “How We Listen,” an introductory, upper-division sound studies course at Binghamton University, with a typical enrollment of 45 students. This assignment asked students to

write a 3-page biography of your voice. You may choose to organize the paper and tell the story however you wish, as long as you consider your experience in light our classroom readings and conversations. . .Here are some questions to help you get started. You do not need to answer all of them, but they may lead you toward some important realizations that you can share through this paper: Have you thought critically about your voice before this class? Why or why not? If so, when did you first become conscious of your voice? Why?What do you love about your voice? Why? Who were your models for learning how to speak and style your voice? Have you ever wanted to change your voice? Why or why not? Have you? Have you liked or disliked your voice at some times in your life more than others?

For the full assignment sheet, click Voice Biography Assignment_F18. For the grading rubric, click Voice Biography Grading Rubric_F18. For the full Fall 2018 syllabus, click english-380w_how-we-listen_fall-2018

While the course usually seats mainly juniors and seniors, Kaitlyn was only a freshman when she wrote this powerful piece!

—

The first joke I can recall took place in fourth grade; then again, I am unsure why it is easier to call it a joke rather than its true word, which I learned only three years ago. Perhaps, given the fact that an eight-year-old is typically still protected from most forms of racism, the fact that I could only categorize this statement as a joke back then is what propels me to do so again as a college student.

I remember that he hadn’t even formed words, he simply yelled out sounds. He pulled on the corner of his eyes and did his best impression of an Asian man’s accent from across the room, letting the whole class know his perception of my race. Ten years later, I realize that this incident was just the start of a lifelong endurance of misjudgment, bigotry, and the largely unwelcome narration of my life.

“Empty Chairs,” Image by Flickr user Renato Ganoza (CC BY 2.0)

In tenth grade, I applied for a student exchange program my high school had recently undertook called Community Wide Dialogue. The program involved my suburban school pairing up with an urban school nearby to discuss, and hopefully dismantle, racist ideals within our city. Although there is no explicit definition of the word “suburban” that details an overwhelming whiteness of its residents, this seems to be the case more often than not. After being accepted into the group, I attended our school’s first informative session about the program. Walking into the room, I quickly noticed that of nearly twenty-five students, I was the only minority they had accepted. I remember thinking to myself, Is this the best they can do? Am I a token minority here? My school had, albeit scarce, minority representation; why weren’t they included?

Being a minority in a program specifically designated for alleviating such ideals meant that I felt very discouraged from speaking in a setting where discussion, specifically from the point of view of minorities, was essential to the goal. I found it was often the white males of both groups speaking for minorities. One day, we studied vocabulary pertaining to racism; this is when I first learned that the term “color blindness” was actually quite racist, as opposed to its intended meaning. Additionally, this is when I first learned the word for what I had been hearing my entire life: microaggressions. My experience suddenly became real; what I had been calling “jokes” was racism.

I felt validated. Being Chinese-American, I am lucky to be protected from more extreme forms of racism that members of the African-American or Latinx population may face. Similarly, I am a minority, but in contrast, I am not perceived as a threat. I am not, as Sandra Bland was, a cause for a repulsive increase in the ease of extending an official white hand. I will never be the tragedy that causes Regina Bradley, a Black professor, to cautiously check herself in order to abide by her grandmother’s warning: “don’t attract attention to yourself.”

The most extreme racism I have endured lies in statements similar to: “Of course you did well on that test!” The only thing that surprised me is that these statements never came from strangers or acquaintances; instead, it was always my closest friends who felt comfortable enough to cause my own sense of discomfort. The most harmful thing about microaggressions is that it is socially unacceptable for the victim to verbalize their being affected by these hurtful phrases. When a victim acknowledges they are hurt, perpetrators are quick to cast their pain aside as hypersensitivity, working to further marginalize them while justifying their own discrimination.

Staying quiet had everything to do with who I was: a female and a minority. I let my intelligence show through my writing and my academic performance. Even if I wanted to speak, I was aware of the little relevance my voice had to others, particularly boys. As Kelly Baker remarks in “Listen to the Sound of My Voice,” “teenage girls were supposed to be seen, but when they spoke they had to master the right combination in order to be heard.” Of course, just like Baker, I, along with several other females, never could master this cultural puzzle.

“Quiet” by flickr user heyrocc, (CC BY 2.0)

I took after most girls when I say that I tended not to speak much in class so as not to make boys uncomfortable by letting them into a female’s darkest secret: I was smarter than most of them. My teachers knew, of course, but they rarely mandated that I spoke out loud. I developed an especially close relationship with my English teacher of two years; he was one of the teachers who had the most insight into my thoughts as written in formal assignments. In other words, he knew my capabilities.

In my second year of his class, he announced that there would be a slam poetry unit in which each student had to write a five-minute poem regarding something they felt strongly about. Most students were quick to write about their perception of the injustice of the school system. I assume this topic was popular due to it being deemed “safe,” meaning the majority of students had the exact same beliefs, and because, as I alluded to before with my deep, dark secret, who would want to make anyone uncomfortable by saying something meaningful?

I decided I would. I could have easily written a poem about a neutral subject that still would have been much more memorable than the others in the class, but my teacher had a faith in me that I decided I would not disobey by lowering my standards for the sake of my classmates’ comfort, so, I did it. I talked about being Asian.

“Poetry Slam,” Image by Flickr user Ländle Slam (CC BY 2.0)

I started the poem with quotes of microaggressions I have heard during my life. It’s said that opening with a joke can lighten the mood, and that was what these sayings were to them, right? I had judged their reactions rightfully; the crowd laughed at the pure absurdity of most of these quotes. When I turned the subject of the poem to how it made me feel, however, is when the class went silent. My voice shook until I reached the third page. I ended up winning the class award for that poem, but do not let that fool you into the amount of eyes that refused to meet mine when I finished speaking.

Their embarrassment is how I knew it had worked. People can cast away a few comments or corrections, but given a platform and five minutes of speech that can not be interrupted, people have to listen. More importantly, they have to listen to me. One of the rules the teacher had put in place regarding our poetry slam was that listeners had to ask each speaker questions after they read their poem in order to receive credit. Our school’s pride and joy, our white, male, three-sport athlete valedictorian, was the first to raise his hand.

“How often do you hear these jokes?”

“Three to five times a day,” I responded loudly, bluntly.

There were no follow up questions.

The word got around. I had people coming up to me and asking me about the poem they had heard about; they began to call it the “Asian poem.” I noticed immediately that the microaggressions stopped, and when a friend witnessed one of the very few I encountered afterwards, her mouth dropped, looking at me to say, “It’s just like the poem!”

My voice had officially become my own through… poetry? I had never considered the ability to find my voice and, in turn, myself through a writing form that I thought to be obsolete. I began writing poems about everything- immigration, love, mental illness, sexual assault- and what was most important is that I was praised. As a Chinese teenage girl, I was heard. I was heard by my classmates, by SUNY Oswego, by Ithaca College, by Scholastic. I realized that poetry could better consolidate and portray my thoughts on a topic than a simple speech. It was the art of speech, the cunning of rhyme scheme and line breaks that finally made what I had to say captivating to others because my skill was admirable. It was an acquired learning, figuring out what to cut, where to end, when to eliminate punctuation to portray certain emotions- it was a combination I actually enjoyed solving.

I ended up using this poem for my college application. I distinctly remember handing in a rough draft of what I thought to be the epitome of a college essay only to have my teacher promptly return it, saying, “You should use your poem instead. That is what is going to show your writing skills- not the typical college essay.” She gathered two other English teachers of mine to consult over the idea. Poetry was not the safest choice for a college application. One of the essay prompts on the application was very vague, simply claiming that the selection of this prompt would indicate that your writing was an explanation of something that the you felt was too important to leave missing from the rest of your application. The four of us easily came to a consensus: this was what colleges needed to see. Call it affirmative action, but I firmly believe it was the quality of my writing–the way it carries the sound and the force of my voice–rather than the subject that got me where I am today.

My secret was finally out; I have shit to say.

—

Featured Image: “Voice” by Flickr User Laurel Russwurm (CC BY 2.0)

—

Kaitlyn Liu is a sophomore at Binghamton University with an intended major of English Literature with a concentration in rhetoric. Kaitlyn takes interest in writing about gender and race along with other intersectional classification systems. She has a passion for nonprofit work, including her previous work with student writers to raise funds for Ophelia’s Place, a nonprofit that provides support for those impacted by body image. Kaitlyn has also been awarded two gold keys for her writing through the Scholastic Art & Writing regional contest. Outside of writing, Kaitlyn enjoys reading historical fiction and singing for Binghamton’s oldest co-ed a cappella group, the Binghamtonics.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Vocal Gender and the Gendered Soundscape: At the Intersection of Gender Studies and Sound Studies — Christine Ehrick

On Sound and Pleasure: Meditations on the Human Voice– Yvon Bonefant

As Loud As I Want To Be: Gender, Loudness, and Respectability Politics — Liana Silva

Hindawi APC comparison 2018-2019

Abstract:

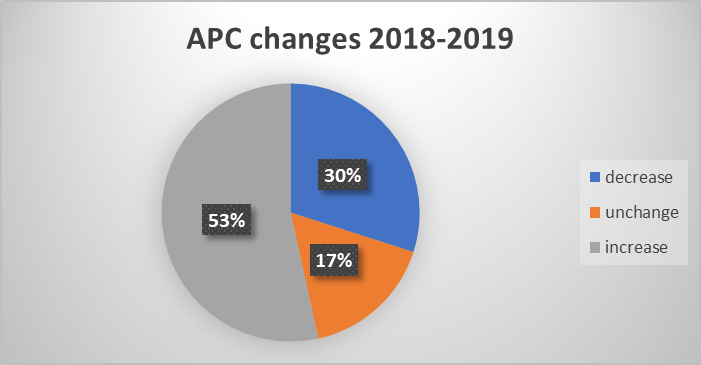

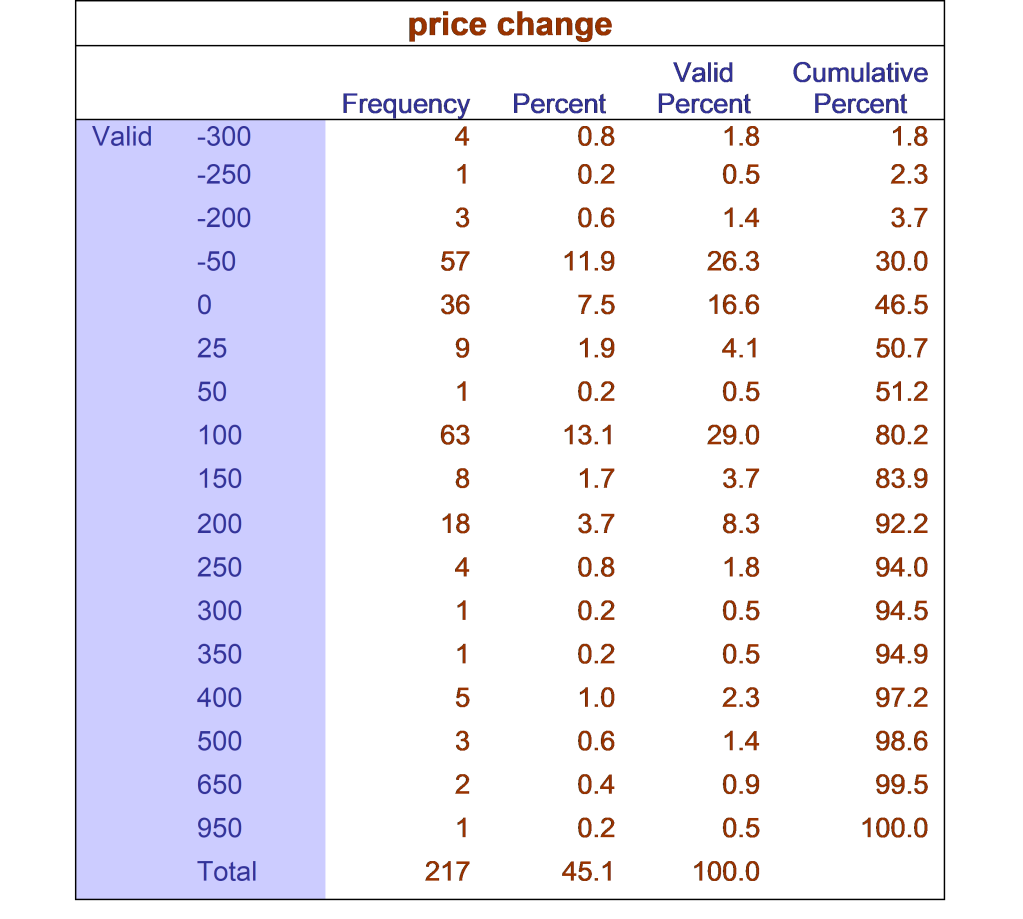

481 Hindawi journals were analyzed. 226 (47%) journals published at some point from 2010 – 2019 have ceased publication, 7 cannot be found on the Hindawi website anymore and 1 has been transferred to another publisher. In 2019, there are 247 journals actively publishing on the Hindawi website. All the journals are charging APCs. The average price is 1186.44 USD, an increase of 14% over the 2018 APC (1040.30 USD). Compared to the US inflation rate for 2018 of 2.44%(“U.S. Inflation Rate 1960-2019” n.d.), the publication fee rises more than 5 times. Among active journals, 17% of the 217 journals did not change in price; 30% journals decreased their price while more than half (53%) of the journals increased price. The amount of price increase starts from 25 USD up to 1350 USD. 14 journals appear to have switched from “no fee” to “fee”, with different APCS from 750 USD to 1350 USD.

Most journals that not found on the website in 2018 now been illustrated ceased on the web page with the specific ceased year and where to find previous publication articles which could be good practice for authors who are trying to find the latest information about specific journals. it also benefits other publishers to follow the lead.

Detail:

Table 1: 2019 Hindawi Journal Publication and APC status summary

Hindawi has 481 journals in 2019. Among these journals, 226 of them were reported ceased on Hindawi’s website. In 2018, most of the ceased journals cannot be found in the website but they have been specified on the webpage about when this journal is ceased and where can readers find previous articles published in the journal. This is a good practice. Here is a example of one of the ceased title.

Price changes 2018-2019

Hindawi has 232 active journals listed on its website in 2018. In 2019, there are 247 journals actively publishing on the Hindawi website. There are 15 journals that cannot be found on the website now can be searched which represents a 6.47% increase in journal numbers of Hindawi.

The average publication fee we found from the Hindawi’s website in 2018 is 1040.30 USD. There are 14 journals that had no publication fee in 2018 in contrast with no journals with no publication fee in 2019 and for most journals the publication fee is 1000 USD per article. The range of APC (article proceeding cost) starts from no publication fee which is zero to 2250 USD.

This average takes into account the 15 journals’ APC for the year 2019. This year, the majority of journals have a publication fee of 950 USD per article. Obviously, every journal found on the Hindawi website does have a publication fee from this year. The minimum cost is 650 USD up to 2300 USD. Graph 1 and Graph 2 below shows the frequency of APC for different prices in two years.

Table 2 2018 & 2019 Hindawi active titles APC status summary

Graph 1: price distribution for 2018

Graph 2: price distribution for 2019

Of the 247 journals total:

- 15 “new” journals are added in 2019 (including in 2019 overall analysis but not 2018-2019 change analysis)

- Journals with status: no publication fee coded as 0 in change analysis.

Total journals included in the price change analysis:

- 2019 overall: 232

- 2018-2019 comparison: 217

Of the 217 titles, as illustrated in the chart and table below, a majority of these journals (53%) increased in prices in USD from 2018 to 2019, while a third (30%) decreased in price and a few (17%) did not change in price.

For the 116 journals that increased in price, the increases in percentages ranged from 2.22% to 95% (slightly under double in price).

Among the 65 journals with APC price decreases, the drop in percentage ranged from 5% to 24%.

Working dataset : https://sustainingknowledgecommons.files.wordpress.com/2019/11/hindawi-analysis_2019_prep_version-0.xlsx

Cite as: Shi, A. (2019). Hindawi APC comparison 2018-2019. Sustaining the knowledge commons. https://sustainingknowledgecommons.org/2019/11/05/hindawi-apc-comparison-2018-2019/

Selected previous posts on Hindawi:

Morrison, H. (2018). Recent APC price changes for 4 publishers (BMC, Hindawi, PLOS, PeerJ). Sustaining the knowledge commons. https://sustainingknowledgecommons.org/2018/04/13/recent-apc-price-changes-for-4-publishers-bmc-hindawi-plos-peerj/

In brief: Hindawi April 2016 – November 2017: mixed picture, price increases a bit concerning

Brutus, W. (2017). Hindawi: comparaison 2016 – 2017. Soutenir les savoirs communs. https://sustainingknowledgecommons.org/2017/04/22/hindawi-comparaison-2016-2017/

In brief: French – highlights: the mode (most common APC) was $600 USD in 2016, $1,000 in 2017

Salhab, J. (2016). Hindawi publisher: 2016 findings and longitudinal comparison of APC rates. Sustaining the knowledge commons. https://sustainingknowledgecommons.org/2016/04/27/hindawi-publisher-2016-findings-and-longitudinal-comparison-of-apc-rates/

In brief: Hindawi previously used a strategy of rotating free publication in journals, mentioned in this post; the most common APC in both 2015 and 2016 was $600; comparing 2010 and 2016 data, we see a mixed picture with some prices increasing and others decreasing.

Salhab, J. & Morrison, H. (2015). Who is served by for-profit gold open access publishing? A case study of Hindawi and Egypt. Sustaining the knowledge commons. https://sustainingknowledgecommons.org/2015/04/10/who-is-served-by-for-profit-gold-open-access-publishing-a-case-study-of-hindawi-and-egypt/

Highlights: as reported by Poynder (2012), Ahmed Hindawi, (from Egypt) founder of Hindawi, confirmed a revenue of millions of dollars from APCs alone – a $3.3 net profit on $12 million in revenue, a 28% profit rate. Hindawi is highly regarded as a leading reputable open access publisher. This commercial Egyptian success story is contrasted with high APC for the most prestigious journals and English-language- only journals that suggest that this approach is not helpful for Egypt’s researchers.

Reference:

“U.S. Inflation Rate 1960-2019.” n.d. Accessed October 31, 2019 from https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/USA/united-states/inflation-rate-cpi

Poynder, R. (2012).The OA interviews: Ahmed Hindawi, founder of Hindawi Publishing Corporation. Retrieved March 10, 2015 from http://www.richardpoynder.co.uk/Hindawi_Interview.pdf

OBP Autumn Newsletter

Welcome to our recent news and releases! We're celebrating the autumn with preparations for OA Week on 21-25 October (please access our Open Access Pack here!); new and award-winning titles, calls for proposals for our Applied Theatre Praxis series and the St Andrews Studies in French History and Culture, and the release of the first OA texbook on conservation biology among many other exciting news items.

Also, our Autumn Catalogue is now available! Please visit here for our latest titles.

Open Access Week 2019

Open Access Week has now finished, but we have updated the pack described below so that it can be of use all year round.

Open Access Week is coming soon! We have created an Open Access Pack for you which you can access here and which includes:

- A guide to Open Access.

- Informative flyers: tailored to researchers and students to raise awareness about how they can take advantage of OA and of the OBP publishing model, both as readers and as potential authors.

- Social Media: a series of tweets/email copy for OA week and beyond. These tweets include information about our work at OBP, about the ScholarLed OA publishers' coalition and broader OA issues. Please choose what information you’d like to share in your social media accounts!

- Slides that can be included in any presentation about Open Access.

- Blogs: last year we released a series of blog post for OA Week: An Academic's Guide to Open Access. This year the ScholarLed blog will be posting throughout the week, with a broad range of contributors discussing Open Infrastructure and its importance for OA publishing.

Please tag us on any of your posts (Twitter @openbookpublish / Facebook @openbookpublish) and share any feedback or comments you'd like by emailing lucy@openbookpublishers.com.

OBP Releases New Metrics Standard

Reliable and accurate metrics about the number of readers we receive are essential to make the case for the value of Open Access books. In 2017, OBP received funding from the European Commission to develop open source tools and standards for everyone that could allow the collection of usage metrics from various Open Access distribution platforms. This project, called HIRMEOS (High Integration of Research Monographs in the European Open Science Infrastructure), has allowed us to rethink, streamline, and expand our previous stats system in order to allow its uptake by the wider publishing community.

Some of OBP’s contributions to the project include a common standard to record and store metrics, and a database that implements standard and modular tools to collect data from the major distributing platforms. As a result of our efforts with the other members of HIRMEOS, we have been able to deploy a shared database containing data for all books published by the project partners.

Although HIRMEOS has now ended, OBP, alongside the OPERAS consortium, are working towards a sustainability plan for the whole metrics suite to be included in the European Open Science Cloud (EOSC).

More information: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/section/92/1

A Fleet Street in Every Town: Prizewinner!

Congratulations to Andrew Hobbs, whose book 'A Fleet Street in Every Town: The Provincial Press in England, 1855-1900' has received the Robert and Vineta Colby Scholarly Book Prize for the best book on Victorian newspapers and periodicals, awarded by the Research Society for Victorian Periodicals.

The selection committee described the book as 'field-defining'; a title that 'convincingly challenges enduring assumptions that London newspapers acted as the national press in the Victorian period.' They exalted its 'meticulous research, originality, and significance for future scholars' of the provincial press in Britain, whilst also noting that it is 'written with imagination, flair and infectious enthusiasm', bringing 'the nineteenth century press to full, vibrant, pulsating life'.

The University of Central Lancashire and the Marc Fitch Fund generously contributed to this Open Access publication.

Conservation Biology In Sub-Saharan Africa

In September we released the first open access textbook on conservation biology in Sub-Saharan Africa, freely available for students and academics working in this region.

Conservation Biology in Sub-Saharan Africa, written by John W. Wilson and Richard Primack, is a textbook created specifically for readers on the continent. It has already been read and downloaded over 3,800 times since publication: this up-to-date study is an essential resource for both undergraduate and graduate students, as well as for professionals and policy makers working to stop the rapid loss of biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere. The book explores the challenges and potential solutions to key conservation issues in Sub-Saharan Africa. It includes boxes covering specific themes written by scientists who live and work throughout the region, together with recommended readings, suggested discussion topics and an extensive bibliography. Furthermore, a wealth of accompanying resources aimed at academics, students and people interested in the field of conservation biology are available, including:

Individual images and chapters:

You can download individual chapters and images here.

Teaching resources:

We will soon be launching a teaching platform on which you will be able to share your notes, lesson plans and presentations with other teachers and academics in the field of conservation biology. If you are interested in uploading your teaching material to this platform, you can do so here. Please notify John W. Wilson here after uploading your content.

Discussion forum:

You can report updates, corrections or add your comments by joining the discussion forum for 'Conservation Biology in Sub-Saharan Africa' here.

This has been a fantastic project to work on and we are wholeheartedly thankful to everyone who made it possible, with a special mention to the authors John W. Wilsonand Richard B. Primackand to The Lounsbery Foundation, which financed its publication.

The PDF, HTML, and XML editions are free to read and download; the EPUB, MOBI, paperback and hardback editions are available from the book's homepage: doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0177.

Our Latest Titles

Over the last three months we have released a range of exciting Open Access titles. Written by Kathryn M. Rudy, one of our returning authors, Image, Knife, and Gluepot: Early Assemblage in Manuscript and Print painstakingly reconstructs the process by which a Netherlandish Book of Hours was created, and discusses its significance as a text at the forefront of fifteenth-century book production. We have developed our own image zooming function to display this book's beautiful illustrations to their best advantage, using open source software that allows the reader to zoom in and view the manuscripts in detail.

Another returning author, Jane Bliss, has published the collection left unfinished upon the death of its original author, Douglas Gray: Make We Merry More and Less: An Anthology of Medieval English Popular Literature.

We're also delighted to announce the publication of a new Open Access textbook History of International Relations: A Non-European Perspective by Erik Ringmar, which pioneers a new approach by explicitly focusing on non-European cases, debates and issues. It is a unique textbook for undergraduate and graduate students of international relations, and anybody interested in international relations theory, history, and contemporary politics.

Our virtual journey through the world continues and our next stop is Asia, and more particularly the Himalayan region, with Selma K. Sonntag and Mark Turin's The Politics of Language Contact in the Himalaya.

Finally, we finish our travels in Lisbon, Portugal, with Maria Manuel Lisboa's latest study Essays on Paula Rego: Smile When You Think about Hell, an incisive monograph containing powerful essays on the major contemporary Portuguese artist.

Some other new interesting titles to browse include Engaging Researchers with Data Management: The Cookbook, an invaluable collection of 24 case studies from across the globe; Labour and Value: Rethinking Marx’s Theory of Exploitation, a provocative study in which Ernesto Screpanti provides a rigorous examination of Marx’s seminal theory of exploitation. We are also excited about the forthcoming publication of Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew, edited by Shai Heijmans and the first title in the new Cambridge Semitic Languages and Cultures, a series created in collaboration with the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge. Finally, a new edition of the late Professor Stephen SiklosAdvanced Problems in Mathematics: Preparing for University will be available for candidates preparing for entrance examinations in mathematics and scientific subjects, including STEP (Sixth Term Examination Paper) in the following months.

To browse any of our latest release or have a look at our forthcoming titles, visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/.

Open Book Publishers and the RNIB

Did you know that OBP works in partnership with the Royal National Institute for the Blind?

We have made all of our books available in PDF and EPUB on the RNIB Bookshare platform, which provides education resources for print-disabled learners, including those with dyslexia or who are blind or partially sighted. Using the EPUB file, the RNIB can make the book available in all accessible download formats, including Braille-ready and DAISY, while the PDFs are available as an accessible PDF.

To find out more about our partnerships visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/section/23/1.

Applied Theatre Praxis Series

Applied Theatre Praxis(ATP) is an OBP series that focuses on Applied Theatre practitioner-researchers who use their rehearsal rooms as "labs”: spaces in which theories are generated, explored and/or experimented with before being implemented in contentious and/or vulnerable contexts. As Helen Nicholson comments (in Etherton and Prentki, 2006:143), "for those of us engaged in research and dramatic practice which take place in community, educational and institutional settings, there is a need to submit our work to critical questioning as part of a continual process of negotiating and renegotiating our ethical positioning”. In this vein, ATP invites writing that is focussed on "theory building” (Hughes and Wilson, 2004:71) ― writing that draws from the author/s’ praxis to generate theory for diverse manifestations of Applied Theatre.

Given OBPs flexible publishing format, this series welcomes both traditional-length and short-form monographs – the latter being applicable to works that fall between a traditional monograph (80,000 words) and a journal article (5,000 words). Furthermore, since OBP supports the integration of multimedia, books in the ATP series could contain audio-visual documentation that explicitly showcases the dynamism involved in theatrical research.

We welcome proposals for new titles in this series. Those interested should contact Dr Alessandra Tosi.

Editorial Board: Nandita Dinesh and Sruti Bala.

Please click here to view and download the leaflet for this series.

St Andrews Studies in French History and Culture Series

St Andrews Studies in French History and Culture, a successful series published by the Centre for French History and Culture at the University of St Andrews since 2010 and now produced in collaboration with OBP, aims to enhance scholarly understanding of the historical culture of the French-speaking world. This series covers the full span of historical themes relating to France: from political history, through military/naval, diplomatic, religious, social, financial, cultural and intellectual history, art and architectural history, to literary culture. The purpose of this series is to publish a range of shorter monographs and studies, between 25,000 and 50,000 words long, which illuminate the history of this community of peoples between the end of the Middle Ages and the late twentieth century. Titles are rigorously peer-reviewed by the editorial board and by external assessors, and they are available both in digital format and hard copies.

This is the first Open Access book series in the field to combine the high editorial standards of professional publishing with the fair Open Access model offered by OBP. You can read more about this series here. You can also get in touch with the Centre for French History and Culture here.

We welcome proposals for new titles in this series. Interested scholars should contact Dr Alessandra Tosi or, if preferred, Dr Justine Firnhaber-Baker, the series' editor-in-chief.

About Us: An Interview with Lucy Barnes

Lucy began working for OBP as an editor in 2016. She has recently taken on a new role as our Outreach Co-ordinator, spreading the word about OA far and wide!

Could you give us a glimpse of how you first became involved with open access?

It was actually when I was submitting my own article for publication; it had to be made openly accessible due to funder requirements. To me this was entirely a matter of compliance with policy—it was an administrative hassle—and the 'Green' OA version of the article seemed very uninspiring, since it was simply my own Word document tucked away in a repository.

It wasn't until I came to work at OBP that I realised the enormous potential of OA: it shouldn't be about compliance, but about the best version of the work being made available to as many readers as possible. Seeing our brilliant books being read by large numbers of people is hugely exciting.

Who should be promoting open access—other than OA publishing houses such as OBP?

Anybody who cares about research! But there's a particular onus on senior academics to blaze a trail: to understand the changes in the publishing landscape that are being driven by OA; to advocate for fair models of access without expensive charges for authors; and to support publishers that are providing such models.

How should OA advocates deal with resistance to OA within institutions and among researchers and faculty?

By engaging in conversation and providing information. There are a lot of myths and misconceptions about open access—sunlight is a great disinfectant as far as these are concerned—and a number of powerful intellectual and ethical arguments in its favour. A key question for researchers opposed to OA is: why publish if not for your work to be read as widely as possible? Arguments that the readership for monographs is specialised, limited and, conveniently, already in the privileged position of being able to access university libraries (or to pay £100 for a book) seem to me to be self-defeating—if the audience for your discipline is really so small, why should the work be publicly funded? Open Access publishing shows us that the audience for monographs in the HSS is broad and deep: just look at our readership statistics! People are hungry to read this work, and this is a really positive indication for the future of HSS disciplines.

Do you think there is enough information available about OA publishing, especially for early career researchers?

There is a wealth of information available; the problem is that it's very diffuse. Researchers have a lot of demands on their time and they don't necessarily want to spend it getting to grips with what is currently a complex and fast-developing area. Part of my job will be to find ways of communicating clearly and concisely with academics about the benefits OA can bring to their research and teaching.

What are your upcoming projects and/or future plans?

Understanding the scope of the challenge I've taken on, and figuring out how to tackle it! In the near future I'm particularly looking forward to our plans for Open Access Week, especially the Open Access pack we're producing and the ScholarLed blog posts we'll be publishing; I'm also excited about heading to the Arctic Circle in November for the Munin Conference!

And finally...

We would welcome any comments or suggestions about our initiatives or about further services we could be providing. If there are any thoughts you would like to share with us, please email laura@openbookpublishers.com or contact us on Twitter or Facebook.

The Sound of Feminist Snap, or Why I Interrupted the 2018 SEM Business Meeting

I begin this essay with an apology, addressed to the Society for Ethnomusicology President Gregory Barz:

I am sorry that I interrupted your opening remarks at least year’s SEM Business meeting. In the moment that I chose to make my intervention, I underestimated the pain that it has clearly caused you. Furthermore, I have come to realize that it was unskillful of me to locate my frustration and anger with you as an individual. The affective release of my voice in that moment could have been better directed towards positive change in a time of great need for many of us. I fully intend to work towards doing better in the months to come, urging anyone who occupies the office of President of this organization to use the power and standing inherent in this position office to take direct steps to address the harms many of its members are experiencing.

Because my intervention arose so quickly and unpredictably—for readers outside of the Society for Ethnomusicology who may not know, I stood up and yelled “You’re a hypocrite!” then left the meeting—it seems worthwhile to explore my actions in a more thoughtful space of written discourse. I want to clarify that my sonic interruption was not premeditated; as I explain below, it arose out of a deep anger and longing for justice. As SEM 2019 convenes in November in Bloomington, Indiana on November 7th, I hope that my disruptive event can be better understood as a call to collective inquiry into the structural factors that constrain our Society from functioning in a healthy way.

Indeed, I am already encouraged by steps that have been taken since the meeting—by President Barz and others—to address some of these concerns. And in the aftermath of this intervention, I have been heartened by the positive and supportive responses I have received from friends and colleagues. Although I had to leave the room in that moment, something meaningful remained just outside.

***

Some backstory: This was the first time I had attended a business meeting; at previous conferences, they had always seemed like a formality that did not concern me. Serving on the Committee for Academic Labor, the Ethics Committee, and as Chair of the Improvisation Section, however, helped me to understand the importance of these formal structures and rituals for the health of our Society. I attended in 2018, therefore, with a sense of curiosity and a longing for positive change, particularly in regard to some of the work coming out of the committees on which I was serving. This longing also arose from a sense of frustration at the lack of receptivity to new ideas by Board leadership—as experienced through a pattern of poor communication around implementation of this work between committees and Board—as well as what I perceived to be a lack of transparency and accountability among Board leadership.

Much of this frustration stemmed from the Board’s failure to implement a minor procedural proposal put forward by the Ethics committee nearly two years prior: that the committee be restructured to be elected rather than appointed. After the first deadline to put the amendment to the full membership passed without comment from the Board, we had to expend a great deal of energy even to receive acknowledgement that our proposals had been received. By the time the committee met again, we had been through over a year of exhausting back-and-forth by email with nothing actually getting done.

Then, in the weeks leading up to the 2018 meeting, a member publicly came forward about experiences of sexual abuse by a now-deceased ethnomusicologist who had served as a senior member of SEM during his lifetime. As a member of the Ethics Committee, I witnessed the email exchange in which her requests for space to address this at the 2018 meeting were first accommodated, then revoked at the last minute; she was finally allowed space to speak in a confusing, unmoderated, ad-hoc session to which the Board assented only after the conference was already underway.

So, when President Barz chose to begin his opening remarks with a paean to civility, lamenting how conflict over social media was causing us to lose our ability to engage in healthy discourse as a unified Society, I became concerned. Many in the audience were aware that both the sexual assault allegation and another credible allegation of ethical misconduct by SEM leadership had been circulating on Facebook in previous months. I heard President Barz’s remarks as a use of his prominent position in SEM to categorize these complaints as “noise.” As Mark Brantner points out in his thoughtful critique of John Stewart’s 2010 “Rally to Restore Sanity,” the idea that sanity operates through “indoor voices” is a deeply ingrained assumption for many.

But in the wake of recent upheavals in the status quo, catalyzed by movements like #blacklivesmatter and #metoo, many hear these “indoor voices” as signifiers of an oppressive status quo. Others have written about the problems inherent in invoking civility in the face of dissent: In a recent piece for The Atlantic, Vann Newkirk argues that in many cases, “the demands for civility function primarily to stifle the frustrations of those currently facing real harm” (2018). In Vox, Julia Azari points out that “Civility is not an end on its own if the practices and beliefs it upholds are unjust” (2018). In these cases, calls for civility came in response to calls by those whose voices are met with silence by the prevailing order.

And allow me to state in no uncertain terms: many of us in the field are currently facing real harm. Since earning my doctorate in Ethnomusicology just over a year ago, I spent eight months without health insurance and now qualify for the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. I’ve strongly considered leaving the Society many times over the past year.

“snapped stick” by Flickr user masterbutler (CC BY 2.0)

I’m also aware that my personal experience is only the tip of the iceberg: so many peers and colleagues have left the Society altogether because of sexual harassment, abuse of power by senior members or advisors, and economic precarity, experienced alone or in horrific combination. These harms are also compounded for my peers who do not share my positionality as a heterosexual, cisgender, white-presenting man with a U.S. passport and a bourgeois class background.

As President Barz continued to speak, my concern—which had lodged itself as a feeling of discontent somewhere in my stomach area—began to rise into my chest as anger, particularly when President Barz began to invoke his authority as a champion of democratic practice within the Society to justify his call to civility. If he truly believed in consensus-building and democracy, I thought, certainly he wouldn’t have opposed an effort to increase democratic accountability on the Ethics Committee. This contradiction generated my experience of what woman of color feminist Sara Ahmed calls “feminist snap” in 2017’s Living a Feminist Life. She described “feminist snap” like this in a May 2017 blogpost:

It is only when you seem to lose it, when you shout, swear, spill, that you have their attention. And then you become a spectacle. And what you brought out means you have to get out. When we think of such moments of snap, those moments when you can’t take it anymore, when you just can’t take it anymore, we are thinking about worlds; how worlds are organised to enable some to breathe, how they leave less room for others. You have to leave because there is nothing left; when there is nothing left.

In other words, I noticed that I seemed to be losing it. In that moment, I drew on my background as an improvising musician to decide how to relate to this intense energy. After exchanging incredulous glances with two colleagues sitting nearby, I decided that I couldn’t sit quietly and let my toxic feeling fester throughout the meeting—I needed to leave, but I didn’t want to leave without registering to people in the room why I had to leave, and there was no space in the official meeting to do so. At the same time, I was aware of the risks inherent in this strategy—especially because I have witnessed how the sound of my voice—a man’s—snapping like this can itself be a trauma trigger for anyone who has been shouted down in a meeting, or otherwise. Thus, the material nature of the spectacle here was different from that described by Ahmed in that it carried with it a timbre of patriarchal violence. Oddly enough, the worlds that I felt were being organized to make it difficult to breathe still afforded me the air for this particular form of breathed expression: a fiery shout. And that sound brought unintended consequences.

“break” by Flickr user David Lenker (CC BY 2.0)

I had wanted there to be no doubt that my departure was a response to President Barz’s remarks, but the power arrangement in the room meant that it would have been difficult to offer a lengthy articulation of my reasoning, given that any utterance would have been received as disruptive and that I did not have access to sound amplification in the large room. (I am reminded here of R. Murray Schafer’s point in The Soundscape : “A man with a loudspeaker is more imperialistic than one without because he can dominate more acoustic space” (1977:77). Schafer’s sexist assumption that only men speaking through loudspeakers is worth noting—as I see it, both men’s and women’s voices could transmit imperialistic sound in this way, but a “snap response” would also be gendered.)

Within a few seconds, I settled on the form my move would take: stand up, shout something concise, and leave the room. The words “You’re a hypocrite!” flowed spontaneously from there—words grounded in my direct experience of the disconnect between Dr. Barz’s present remarks and previous actions. Immediately upon leaving the room, an adrenaline rush flowed out of my body and I staggered towards a nearby bench, where I collapsed to catch my breath.

Again, I regret that these remarks focused on President Barz as an individual. Had I more time to think through what I would have stated, perhaps “This is unacceptable,” “These actions are hypocritical,” or “Please don’t ignore us” would have been what came out. And yet, by this point, the sound of this intervention had already been determined by the immediate constraints of the situation: had I chosen to sound in a way that was coded as “civil”, I literally would not have been heard by more than a few people in the room.

“broken cedar” Image by Flickr user Erik Maldre (CC BY 2.0)

Even after this intense incident, my experience of the conference in Albuquerque was very positive overall. SEM is full of brilliant emerging scholars asking extremely important questions; it was especially encouraging to see more attention being brought to the imperatives of decolonization and anti-racism. At the same time, in order for these inquiries to be truly productive, we still need to turn our analysis towards the ways in which the status quo of our governance practices unintentionally reproduce systems of oppression and create harm. Tamara Levitz, in her recent article “The Musicological Elite,” sheds light on how this has been the case within an adjacent academic organization, the American Musicological Society. She writes, “My premise is that musicologists need to know which actions were undertaken, and on what material basis, in building their elite, white, exclusionary, patriarchal profession before they can undo them.” (2018:43). Despite some evident wishful thinking to the contrary, SEM reproduces harm in similar ways and would benefit from similar institutional self-reflection.

By yoking itself to the project of the North American university system, the Society for Ethnomusicology has created strong incentives for members to go along with what Abigail Boggs, Eli Meyerhoff, Nick Mitchell, and Zach Schwartz-Weinstein call the “Modes of Accumulation” of these institutions. We must urgently turn towards critical institutional self-examination to consider how we can change our practices to resist complicity with these forms of professionalized domination and control.

In order to do so, we need better mechanisms for dissent and communication, especially when we have the rare opportunity for face-to-face communication. We must address what seems like an increasing tension between preserving the institutions of tenure-track music academia and the broader needs of the Society’s full membership. Crucially, Ahmed turns to listening as a key methodological practice for locating “feminist snap”:

To hear snap, one must thus slow down; we also listen for the slower times of wearing and tearing, of making do; we listen for the sounds of the costs of becoming attuned to the requirements of an existing system. To hear snap, to give that moment a history, we might have to learn to hear the sound of not snapping. Perhaps we are learning to hear exhaustion, the gradual sapping of energy when you have to struggle to exist in a world that negates your existence. Eventually something gives.

In this case, listening for the silences—and silencing—that preceded this instance of “snap”may be useful. To my ear, they index the “sound of not snapping”: the unanswered emails, averted eye contact, unreturned phone calls—these are the sounds of a snap to come. These silences are empowered by our collective reliance on a discourse of “civility,” propped up by formal procedures like Robert’s Rules of Order, that deems certain types of sounds and communication to be out of bounds. Indeed, as Hollis Robbins has observed, “Under Robert’s Rules, silence equals consent.” Listening for feminist snap would require a commitment to naming these silences—and allowing space for them to be spoken into.

I sincerely hope that my moment of becoming a spectacle can spark more productive conversations and deeper listening. Still, the magnitude of the challenges that we face to align our governance practices with shared institutional values will require creative solutions. I am confident that our experience and training as listeners can bring us to a fuller engagement with democratic processes—and that this can lead us towards productive solutions. This work is already being done by many groups and individuals within the Society, such as the Committee for Academic Labor, the Crossroads Committee, the Disability and Deaf Studies Special Interest Group, the Diversity Action Committee, the Ethics Committee, the Gender and Sexualities Task Force, the Gertrude Robinson Networking Group, the Section on the Status of Women, and many others. I am confident that members of these groups are actively working to build spaces that allow for us to listen into the structural and cultural changes we desperately need.

In the meantime, I remain committed to seeking out collaborative solutions to the challenges we face. Please feel free to reach out to me by email with any feedback you feel compelled to share. Furthermore, if you would like to contact the Ethics Committee about any issues of ethical import to the Society, you may do so here. Anonymous submissions are also possible through this portal.

I’d like to close this essay with an apology, as well—addressed to all of my peers who have experienced harm or abuse through their involvement with SEM: I am truly sorry that I have not done more to work towards redress for the harms that you have experienced. I am also deeply sorry that I have not done more to examine how my own desire to see projects through in this community has led me to ignore signs of harm taking place. I’ve had the good fortune of being able to express this to a few of you in person, and I am tremendously grateful for the opportunity. For anyone else who would like to reach out, I will commit to listening. For us to do better, I need to do better.

Thank you for taking the time to read this statement—I look forward to continuing our work together to create a sustainable future for the practice of ethnomusicology.

—

Featured Image: “I Broke a String” by Flickr User Rowan Peter (CC BY-SA 2.0)

—

Alex W. Rodriguez is a writer, improviser, organizer, and trombonist. He holds a PhD in Ethnomusicology from UCLA, where his research was based on fieldwork conducted in Los Angeles, California from 2012-2016, Santiago, Chile from 2015-2016, and Novosibirsk, Siberia in fall 2016. Alex is currently based in Easthampton, Massachusetts, USA.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

My Music and My Message is Powerful: It Shouldn’t be Florence Price or “Nothing” –Samantha Ege

becoming a sound artist: analytic and creative perspectives–Rajna Swaminathan

Sounding Out Tarima Temporalities: Decolonial Feminista Dance Disruption–Iris C. Viveros Avendaño

On Whiteness and Sound Studies–Gustavus Stadler

Canonization and the Color of Sound Studies –Budhaditya Chattopadhyay

Out now: TOD #31: Media Do Not Exist

Out now: TOD #31: Media Do Not Exist

INC is happy to announce the publication of Media Do Not Exist: Performativity and Mediating Conjunctures by Jean-Marc Larrue and Marcello Vitali-Rosati.

You can download and read the book here: https://networkcultures.org/blog/publication/tod31-media-do-not-exist/

Dr Michael Noble Special Edition Call for Submissions

Ajol, une plateforme franco-anglaise sans filtre en français

Résumé

La plateforme publie 524 revues issues de 32 pays d’Afrique. 39 revues sont en français. Malgré ce contenu francophone, Ajol ne dispose pas un filtre pouvant repérer les revues en français. Pour y arriver, il faudrait d’abord reconnaitre ou repérer les pays francophones sur la liste à sa page, Une. De plus l’on remarque que la plateforme est unilingue.

Visité par plus 200.000 personnes par mois, AJOL est une plateforme qui a été créée en 1998 à Oxford en Angleterre. Sa mission est de mettre à disposition du public en ligne une collection de publications des recherches académiques en provenance d’Afrique. D’importants domaines de recherche en Afrique (Biology & Life Sciences, Health, General Science, etc.) ne sont pas connus dans des publications de pays développés. Pour AJOL, Internet est un bon moyen d’augmenter l’accès à ses recherches afin de permettre aux chercheurs du monde entier. Le site de AJOL héberge 524 revues avec169 652 articles en texte intégral de 32 pays. De nos jours, son siège social se trouve en Afrique du Sud (Ajol, 2019). Deux types de frais d’accès qui permettent d’accéder aux articles non open access sont accordés aux chercheurs et aux étudiants d’une part, et un autre aux bibliothèques et cela en fonction du pays où la demande est émise.

Dans ce travail nous présentons les activités de Ajol. Notre démarche repose sur le protocole d’évaluation de The Charleston Advisor. il stipule que l’on que : «As a critical evaluation tool for Web-based electronic resources, The Charleston Advisor will use a rating system which will score each product based on four elements: content, searchability, price and contract options/ features» (The Charleston Advisor, 2019).

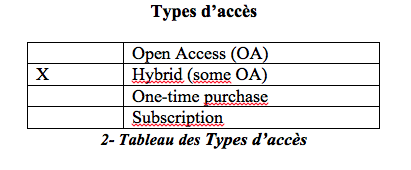

AJOL est une plateforme hybride. De ses 524 revues, 262 sont en accès libre. Le système AJOL est entièrement basé sur des logiciels et des technologies Open Source en l’occurrence : Open Journal Systems developed de Public Knowledge Project (PKP) au Canada, Operating System, etc. AJOL n’accepte pas les publications des auteurs de façon individuelle. Il faut passer par une revue pour être publié (AJOL, 2017 (a)).

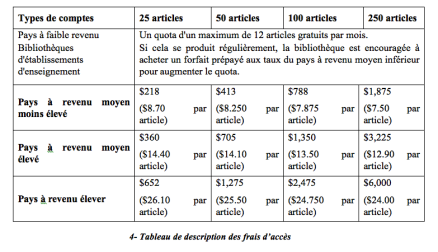

Options de tarification

Les frais de publication proposés pour le téléchargement des chercheurs, des étudiants, etc. (AJOL, 2017 (e)). Ce sont :

Pour les bibliothèques ont leurs frais qui sont différents de ceux des chercheurs (AJOL, 2017 (d)).

Aperçu du produit / Description

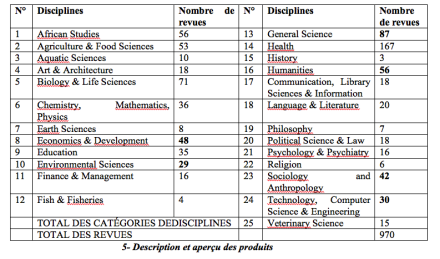

Deux produits sont mis à la disposition à la disposition du public: des publications payantes et non payantes. AJOL publie 169 652 articles en texte intégral dont 110 502 sont en accès libre. Ces articles sont issus de 527 revues, dont 262 en accès libre (AJOL, 2017 (a)). 25 disciplines reparties.

Les disciplines contenues dans leurs publications les suivantes :

L’on constate que 6 nouvelles revues (en gras dans le tableau ci-dessus) se sont ajoutées depuis 2017 au niveau des champs :

– des Sciences environnementales : 29

– de la Sociologie et de l’anthropologie : 42

– de la Technologie, de l’informatique et de l’ingénierie 30

– des Sciences générales : 87

– de l’Économie et du développement : 48

– Sciences humaines : 56

Les champs de la santé (Health (167)) et de (General Science (87)) arrivent en tête du nombre des catégories de sujet et sont toutes évalués par les pairs (peer reviews). AJOL s’adresse spécifiquement aux chercheurs et aux bibliothèques. Selon les auteurs du site Web, AJOL a un PageRank Google de 8. Il est visité par 200 000 personnes par mois à travers le monde. L’onglet «Using AJOL» permet d’accéder la feuille de route qui indique le processus de recherche (AJOL, 2017 (b)).

Interface utilisateur / Navigation / Recherche

La plateforme publie 524 revues issues de 32 pays d’Afrique. 39 revues sont en français. Malgré ce contenu francophone, Ajol ne dispose pas un filtre pouvant repérer les revues en français. Pour y arriver, il faudrait d’abord reconnaitre ou repérer les pays francophones sur la liste à sa page principale. De plus l’on remarque que la plateforme est unilingue.

Une particularité est que son interface donne accès facilement aux produits. La fonctionnalité «Journal» donne directement accès aux différentes catégories de sujets qui sont traités. On peut les obtenir par pays sur une facette où tous les pays sont affichés. Et les facettes par pays permettent de spécifier sa recherche. Toutefois, les informations sur les auteurs et les rédacteurs de la plateforme sont inexistantes. Par exemple, l’on n’a pas les noms et l’organigramme de cette organisation à but non lucratif (The Charleston Advisor, 2019).

Le site web de AJOL demande une inscription pour naviguer sans restrictions. Au niveau de la principale, 5 onglets permettent de se connecter. «Afriacn Journals Online (AJOL)» est fixé sur la page une. L’onglet «Journals» conduit à la liste des catégories de publication, «Advanced Search» ouvre sur un champ de recherche plus spécifique par facettes. «Using AJOL» permet de trouver des articles en accès libre de toutes les catégories de revues par titre, d’enregistrer le profile de votre revue et de donner une feuille de route pour les recherches.

Ajol donne une occasion aux différentes de s’enregistrer et diffuser leurs propres articles. Il indique aussi la liste des frais que chercheurs et auteurs doivent payer. «Ressources» connecte les visiteurs sur d’autres revues hors de l’Afrique. Par ailleurs, une colonne à facette située à droite du site indique les catégories, par ordre alphabétique et par pays où l’on peut télécharger les articles (AJOL, 2017 (a)).

Contenu

Ajol a pour mission de valoriser et de diffuser les publications africaines. Dans ce sens, la plateforme remplit parfaitement ses objectifs. Elle diffuse 524 revues examinées par les pairs, dont plus de la moitié (306) avec des frais pour le téléchargement. Le reste est en accès libre. On remarque que la grande partie est en anglais (497). 39 revues en français. Bien que le contenu soit diversifié, les études sur les Sciences de l’Information et de la bibliothéconomie sont très restreintes (18 revues avec la Communication) par rapport aux sciences de la santé (167).

Tarif

Les revenus provenant des frais de téléchargement de l’article pour les revues d’abonnement sont envoyés au journal d’origine (moins le coût d’amortissement d’AJOL). Par contre toutes les revues en accès libre sont à la portée de tous. Les frais sont fixés en fonction des pays. Les pays pauvres payent moins que les plus riches. Les critères qui définissent ces pays sont basés sur les statistiques de la Banque Mondiale (The World Bank, 2017). Évidemment, les frais des bibliothèques sont plus élevés que ceux des chercheurs et cela en selon les pays.

Par ailleurs, une des compétitions de AJOL est The Sabinet African ePublications (African Journal online archive). Son site publie 500 revues regroupant 64 catégories de sujets, dont 86, en Open Access. Il est créé depuis 2001. Cette plateforme a la particularité de ne pas publier son organigramme comme AJOL. Nous n’avons pas retrouvé ses frais de publication. Par contre, elle publie un grand nombre de revues de l’Afrique du Sud (The Sabinet African ePublications, 2017).

La bibliothèque numérique en ligne africaine (AODL) est un portail de collections multimédia sur l’Afrique. Les auteurs collaborent avec le Centre d’études africaines de l’Université d’État du Michigan, ainsi que des organisations du patrimoine culturel en Afrique pour construire cette ressource (AODL, 2019).

Dispositions d’achat et de contrat

Les revues qui choisissent de publier dans un modèle d’accès ouvert ont leur texte complet en ligne pour le téléchargement gratuit. Les bibliothèques peuvent ouvrir un compte de téléchargement d’articles prépayés avec AJOL pour accéder aux titres des partenaires qui facturent leur contenu. Cela permet aux utilisateurs d’obtenir plus facilement des articles en texte intégral auprès de AJOL. L’accès aux articles d’abonnement est effectué par un mot de passe ou par leur logiciel qui sélectionne automatiquement la gamme d’adresses IP au choix de l’établissement. Des indications expliquent qu’il n’y a pas de restriction de temps pour la remise des articles. Les comptes peuvent être complétés à tout moment. Pour vérifier la catégorie dans laquelle votre pays se trouve, il est demandé de se référer listes de pays de la Banque mondiale. L’adresse suivante : info@ajol.info permet aux revues de se faire créer une installation un compte.

Conclusion

La plateforme AJOL est hybride, certains articles sont payants. Pour gérer le flux de clients, une souscription exige un «username» et un mot de passe pour la navigation sur le site. De plus, l’accession aux documents payants sont soit par abonnement ou directement. Ce qui filtre les visiteurs. Il y a un panier dans lequel tout souscripteur peut collectionner les articles qu’il souhaite acheter. Il n’y a pas d’options qui déterminent un groupe particulier avec des faveurs spécifiques.

Références

AJOL, (2017) (a). African Journals Online (AJOL)) (2017). http://www.ajol.info/ Visité le 30/102019

AJOL, (2017) (b). African Journals Online: Browse by Category. http://www.ajol.info/index.php/index/browse/category Visité le 30/102019

AJOL, (2017) (c). FAQ’s http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajol/pages/view/FAQ#A1 Visité le 30/102019

AJOL (2017) (d). How Librarians can use AJOL. http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajol/pages/view/LIBhowto . Visité le 30/102019

AJOL, (2017) (e). How Researchers can use AJOL http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajol/pages/view/RESHowto Visité le 30/102019

The Sabinet African ePublications (2017). http://journals.co.za/. Visité le 30/102019

The African Online Digital Library (AODL) (2017). http://www.aodl.org/ Visité le 30/102019

The Charleston Advisor, (2017) About TCA. http://www.charlestonco.com/index.php?do=About+TCA Visité le 30/102019

The World Bank (2017) Data and Statistics. http://econ.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/DATASTATISTICS/0,,contentMDK:20421402~menuPK:64133156~pagePK:64133150~piPK:64133175~theSitePK:239419,00.htmlVisité Visité le 30/102019

SO! Amplifies: Die Jim Crow Record Label

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome!

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome!Die Jim Crow (DJC) is the first US record label dedicated to recording formerly and currently incarcerated musicians. The mission of DJC is to provide formerly and currently incarcerated musicians a high-quality platform for their voices to be heard. DJC sprang from Executive Director Fury Young’s communications with currently incarcerated individuals by letter and was originally slated to be a single concept album, inspired by Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow and Pink Floyd’s The Wall. The project quickly grew into much more than that.

For me, death to Jim Crow means a death to stereotypes, to misconceptions of the ‘Other.’ There is no Other. The term ‘Jim Crow’ comes from a song which satirizes a slave. I see much parallel to the way our society views those incarcerated: that they are ‘lesser than;’ merely criminals. We are changing this narrative through music. – Fury Young

DJC records, produces, and releases music written and performed by formerly and currently incarcerated individuals. Prison staff and others working inside, such as volunteers or other program facilitators, refer incarcerated collaborators to DJC. Executive Director Young and Deputy Director BL Shirelle correspond by mail or digitally with these individuals to help prepare their musical contributions for in-prison recording sessions. Young, Shirelle, and other producers identify promising Project Managers inside each facility who help guide the music creation and recording process.

Music is recorded in prisons, homes of the formerly incarcerated, and Brooklyn studio revolutionsound, produced in the same studio, and then widely released through digital and physical channels. We currently have ongoing programming at 2 prisons in South Carolina and have recorded at a total of 5 prisons since 2015, 3 of which we are seeking to regain access to because of prison administration changes.

Our Board of Directors comprises 40% formerly and currently incarcerated individuals, ensuring that Die Jim Crow is steered by those who have direct lived experience with the issues informing our work. Deputy Director Shirelle is a formerly incarcerated musician acting as co-Label Manager with Young, bringing her unique set of experiences and talents to Die Jim Crow.

Over the past several years, Young has formed solid relationships built on trust with a number of formerly and currently incarcerated artists and has learned how to navigate the challenging process of gaining access to prisons to work with incarcerated individuals. As Fury told SO!’s Managing Editor Liana Silva,

Gaining access is tough. It can take months, even years to navigate through to the right people and get an Okay. Once you’re in, you’re in. But then you need to deal with censorship from the top brass and navigating through that. There are all types of unforeseen challenges that pop up when you least expect them to — but it really comes from above. In terms of recording on the inside, besides the typical band shit like “this guy’s ego is getting in the way” or “this guy won’t play with the band,” the making music part is the fun part.

Earlier this year–March 2019–Young took a trip to Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, the experience inspired a big shift In Die Jim Crow toward founding the non-profit label. The journey began in New Orleans with a home recording of Albert Woodfox, who lent his voice to music for the first time. Mr. Woodfox spent 43 years in solitary confinement in Louisiana, the longest of any solitary prisoner in US history. Fury also recorded a video interview with Albert about his experiences with music while inside.

From NOLA, Fury picked up co-producer and engineer Doc (aka Dr. Israel) in Mississippi–who has been part of the DJC team since 2015– where they spent two days recording four rappers at a juvenile prison — Central Mississippi CF Youthful Offender Unit. They spent the next 10 days in South Carolina recording a total of 22 artists at a men’s and a women’s prison: Allendale CI and Camille Griffin Graham CI. When they got home, Fury noted at a Board of Directors meeting: “This is becoming a record label.” He had already discussed it with Shirelle and senior advisor Maxwell Melvins, both DJC artists and board members, and the consensus was clear. A similar reaction was palpable at the board meeting. Stefanie Lindeman, a non-profit veteran and board member, brought up, “OK, we need to put together a three year strategic plan immediately.” And from there, Die Jim Crow Records was born.

And what will Die Jim Crow records sound like? Fury told SO! that

There’s a lot of hip hop and soul. Most of our artists are black and that is the music many of them grew up on. But as we transition into a record label and open up to new projects, we’re becoming more of a melting pot. All types of influences go into the stew. Right now we’re working on a straight hip hop EP at a women’s prison in South Carolina — kinda like a Lauren HIll/Rapsody vibe, and then a project called The Masses at a men’s SC prison — which has a full band and several emcees. They’re sorta like The Roots meets Wu Tang in a southern prison. But in other states we’ve recorded plenty of rock and even Native American chants. If you listen to the EP, you’ll get a sense of the sundry sounds.

Young has already recorded and released a high-quality EP with these musicians and recorded a significant library of unreleased music.

Over the next few years, DJC will continue to grow through re-releasing and repackaging existing content, cultivation of current and new artists, and development of new projects, as well as live shows, events, and tours. DJC will release 1 EP and 1 mixtape per year. The first release will be the Die Jim Crow LP, accompanied by a book and feature film documentary in 2022. By November 2020, DJC will release The Masses EP. On May 1, 2020, DJC will re-release the Die Jim Crow EP, release the “First Impressions” single and video from the EP, and begin the “Single of the Month” initiative, putting out both prerecorded songs and new works.

Die Jim Crow is currently engaged in a Kickstarter campaign for their project through 8 pm tonight, Monday 28, 2019– click here to donate to launch the label and/or read (and hear) more about the project!

—

Featured Image: Some of the artists Die Jim Crow has worked with in GA, OH, IN, CO, PA, CA, NY, NJ, MD, KS, AL, TX, and LA. (L-R each row): Johnnie Lindsey, Leon Benson, Malcolm Morris, Maxwell Melvins, Michael Austin, Dexter Nurse, Valerie Seeley, Spoon Jackson, Tameca Cole, Michael Tenneson, Mark Springer, Obadyah Ben-Yisrayl, Cedric “Versatile” Johnson, Lee Lee, Anthony “Big Ant” McKinney, Ezette Edouard, Pastor Anna Smith, BL Shirelle, Carl Dukes, Norman Whiteside, Sedrick Franklin, Charles “C-Will” Williams, Apostle Heloise

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Regulating the Carceral Soundscape: Media Policy in Prison—Bill Kirkpatrick

Prison Music: Containment, Escape, and the Sound of America—Jeb Middlebrook

SO! Podcast #75: Wring Out Fairlea—Emma Russell

SO! Amplifies: Carleton Gholz and the Detroit Sound Conservancy