For a number of semesters, I invited composition students to explore the idea of using the mixtape as a lens for envisioning a writing assignment about themselves. Initially called “The Mixtape Project,” this auto-ethnographical assignment employed philosophies from various scholars, but focused on Jared Ball and his concept of the mixtape as “emancipatory journalism.” In I Mix What I Like!: A Mixtape Manifesto, Ball pushed readers to imagine the mixtape as a counter-systematic soundbombing, circumventing elements of traditional record industry copyright practices (2011).

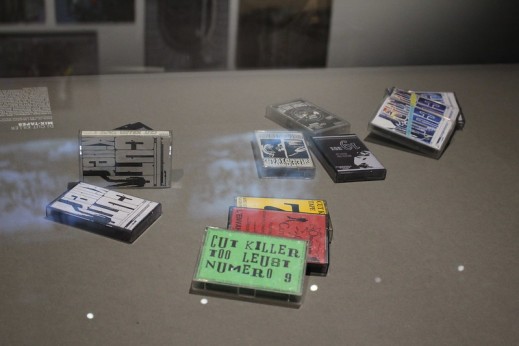

Essentially, a DJ could use a myriad of songs from different artists and labels to curate a mixtape with a desired theme and overarching message, then distribute the mixtape as a “for promotional use only” artifact. Throughout the 1980s, but predominantly in the 1990s and early 2000s, many DJs used mixtapes as the medium to promote their DJ brands and generate income. It wasn’t long before labels began to give hip-hop DJs record deals to release “album-style” mixtapes where the DJs record original content from artists made specifically for the DJ album (see DJ Clue, Funkmaster Flex, Tony Touch). This idea evolved into producer-based compilation albums, best depicted today by global icon DJ Khalid. Rappers also hopped on the mixtape wave, using the medium to jump-start their careers, create a “street buzz” around their music, and ultimately gauge the success of certain songs to craft and promote upcoming albums.

Image by Flickr User Backpackerz: “K7 mixtape – Exposition Hip Hop, du Bronx aux rues arabes (Institut du monde arabe)” (CC BY-SA 2.0)

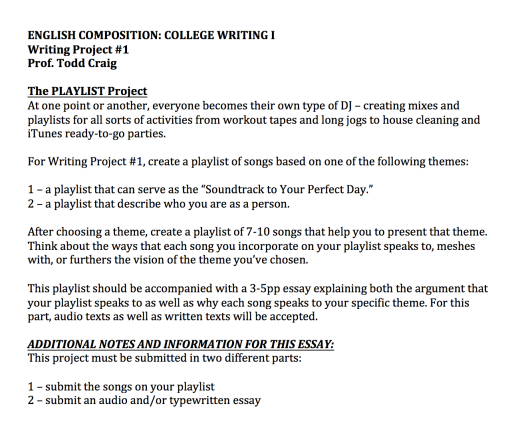

The assignment revolved around mixtape framework in the earlier portion of my teaching career. Most recently, I began to realize as my students evolve (and I simultaneously age), that the “mixtape” – a sonic artifact distributed on cassette tape or CD – is becoming more remote to students. This thinking led to revising the assignment with a more contemporary twist. Thus, “The Playlist Project” was born: the first in a set of four major writing projects in a first-year writing classroom. The ultimate goal of the assignment was to immediately disrupt students’ relationships with academic writing, and to help them (re)envision the ways they embrace some of the cultural capital they value in college classrooms. Be clear, this was a particular type of mental break for students, a shift that was welcomed yet also uncomfortable for them.

“I Get It How I Live It”: Framing and Foregrounding the Assignment Set-Up

The course started with readings on plagiarism, intertextuality, and the hip-hop DJ’s use of sampling, curating, and storytelling. Next were readings by hip-hop artists describing their creative process and detailing their artistic choices sonically. These early readings helped pivot students from their stereotypical notions of what college writing courses – and writing assignments – looked like, and how they could enter scholarly discourse around composing. This conversation was foregrounded in students’ knowledge that they bring with them into the new academic space in the college classroom. My goal was to really focus on student-centered learning and culturally relevant pedagogy; ideally, if you are immersed in hip-hop music and culture, I want you to share that knowledge with the class. This sharing begins to create a community of thinking peers instead of a classroom with an English professor and a bunch of students who have to take the course “cuz it’s required in the Gen Ed, so I can’t take anything else ‘til I pass this!”

My research is entrenched in both hip-hop pedagogy and culture, specifically looking at the DJ as 21st century new media reader and writer. I liken my role as instructor to that of the DJ: a tastemaker and curator for the ways we understand sonic sources we know, and couple them with new and necessary soundbites that become critical to the cutting edge of the learning we need. I’ve engaged in the craft of DJing for more than half of my life, and use DJ practices as pedagogical strategies in my classroom environments.

DJ Rupture, Image by Flickr User JD A (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The outcome of this curatorial moment was “the Playlist Project.” Students were asked to create their own playlists, which served as mixtapes that either “described the writer as a person” or “depicted the soundtrack to the writer’s perfect day.” This assignment was due during Week 6 of a 16-week semester, and was the first major writing assignment within the course. The assignment called for two specific parts: an actual playlist of the songs and an essay which served as a meta-text, describing not only the songs, but also the reasons why the songs were chosen and sequenced in a specific order. As an example, the guiding text we used was a DJ mixtape I created called “Heavy Airplay, All Day.”

“Heavy Airplay, All Day with No Chorus”: DJ Mixtape by Todd Craig

My playlist was a DJ-crafted tribute to a family friend who passed away in the summer of 2017: Albert “Prodigy” Johnson, Jr. Hearing the news of his untimely death reverberated through my psyche on that warm June afternoon; I remember meeting Prodigy when I was 15 years old. Many avid hip-hop listeners not only know Prodigy as one of the signature vocalists of the 1990s New York hip-hop sound, but also as one of the premier lyricists responsible for a shift in sonic content from emcees in New York and globally. His voice is one of the most sampled in hip-hop music.

One of the most anticipated moments of the mid 1990’s was the release of Prodigy’s first solo album, H.N.I.C. P was already shaking the industry with his lethal and bone-chilling visuals in his verses. But everyone knew he was on his way to dominance upon hearing the single “Keep it Thoro.” On this Alchemist-produced record, P basically broke industry rules in regards to typical hip-hop song construction; his verses were longer than the traditional 16-bar count, and the song had no chorus.

He returned to hip-hop basics: hard-hitting rhymes with undeniable visuals served atop a sonic landscape that kept everyone’s head nodding. P ends the song with the classic line “and I don’t care about what you sold/ that shit is trash/ bang this – cuz I guarantee that you bought it/ heavy airplay all day with no chorus/ I keep it thoro” (Prodigy 2000).

It was only right for me to create a tribute mixtape for Prodigy. And it felt right to start the Fall 2017 semester with the Playlist Project that used a shared text that celebrated and honored his memory. It highlighted the soundtrack to my perfect day: having my friend back to rewind all the memories that come with every song.

“I Got a New Flex and I Think I Like It”: (Re)inventing Mixtape Sensibilities in the Comp Classroom

The Playlist Project was aimed at achieving three different outcomes. The first goal was to invite students to use audio sources to envision a soundscape that explains a thread of logic. These sonic sources would hold as much value in our academic space as text-based sources, and would allow them to (re)envision what “evidence-based academic writing” looks like. Thus, students could utilize their own cultural capital to negotiate sound sources of their choosing.

The second was to get students to use DJ framework to think about sorting, sequencing and organization in writing. In our class discussions, one of the critical objectives was to get students to understand the sequencing of divergent sound sources could drastically alter the story one is trying to tell. Overall aspects of mood, tone, and pacing all become critical components of how a message is expressed in writing, but it becomes even more evident when thinking about the sonic sources used by a DJ. Each song – a source in and of itself – is a piece of a puzzle that constructs a picture and tells a story. Starting with one source can create a completely different effect if it is reconfigured to sit in the middle or the end. Explaining these sonic choices in text-based writing would be the second step in the assignment.

The second was to get students to use DJ framework to think about sorting, sequencing and organization in writing. In our class discussions, one of the critical objectives was to get students to understand the sequencing of divergent sound sources could drastically alter the story one is trying to tell. Overall aspects of mood, tone, and pacing all become critical components of how a message is expressed in writing, but it becomes even more evident when thinking about the sonic sources used by a DJ. Each song – a source in and of itself – is a piece of a puzzle that constructs a picture and tells a story. Starting with one source can create a completely different effect if it is reconfigured to sit in the middle or the end. Explaining these sonic choices in text-based writing would be the second step in the assignment.

Finally, students would engage in editing by joining both sound and text based on a theme they have selected. Again, sequencing becomes a critical DJ tool translated into the comp classroom. Using this pedagogical strategy echoes the ideas of using DJ techniques such as “blends” and “drops” as viable teaching tools (see Jennings and Petchauer 2017). Students would need to critically think through an important question: in creating the playlist, how does one manipulate and (re)configure sound to create a sonic landscape that “writes” its own unique story?

“But Does It Go In the Club?”: Outcomes and Initial Findings of The Playlist Project

The first iteration of the Playlist Project bore mixed results. Students found it difficult to think of this project as one whole assignment consisting of three different parts. Instead, they envisioned each of the three different pieces as isolated assignments. So the playlist was one part of the assignment. They picked the songs they liked, however ordering and sequencing to convey a logical theme or argument fell from the forefront of their composing. The essay then became its own piece divorced from the organic creation of the playlist. Thus, students weren’t “engaged in telling the story of the playlist.” Instead, students were making a playlist, then summarizing why their playlists contained certain songs.

For students who were more successful integrating the elements of the assignment, we were able to have rich and fruitful classroom conversations about both selection and sequencing. For example, one student chose the theme of “the Soundtrack to the Perfect Day.” Within that theme, the student chose the song “XO TOUR Llif3” by Lil Uzi Vert.

In the song’s hook, he croons “push me to the edge/ all my friends are dead/ push me to the edge/ all my friends are dead” (Vert 2017). When this song came up in class discussion, we were able to have a formative conversation around the idea that a perfect day entailed all of someone’s friends being “dead.” This also sparked a conversation about the double meaning of the quote; it didn’t stem from traditional print-based sources, but instead arose from a student-generated idea based in the cultural capital of the classroom community. In this moment, I was able to learn more from students about the meteoric rise in relevance of both the artist and the song which seemed to depict an extreme darkness.

“Big Big Tings a Gwaan”: Future Tweaks and Goals for The Playlist Project

Moving forward with this assignment, I have considered breaking the assignment up into three pieces for more introductory composition courses: constructing the playlist, sequencing the playlist, and writing the meta-text. In this configuration, the meta-text would truly become the afterthought (instead of the forethought) of the sonic creation. As well, more in-depth soundwriting could emanate from the playlist construction, manipulation, (re)sequencing and editing. I also plan to use the assignment with a more advanced-level composition course to gauge if the assignment unfolds differently. Using an upper-level course to attain the trajectory of the assignment may be helpful in walking backwards to calibrate the assignment for students in introductory-level classes.

Another objective will be to move away from just a “playlist” and back into a “digital mixtape” format, where the playlist songs and sequencing become the fodder for a one-track, “one-take” DJ-inspired mixtape. While students don’t have to be DJs, creating a singular sonic moment digitally may imbed students in marrying the idea of soundwriting to depicting that sonic work in a meta-text. This work may also engage students in constructing sonic meta-texts, thereby submersing themselves in soundwriting practices. This work can be done in Audacity, GarageBand and any other software students are familiar with and comfortable using.

—

Featured Image: By Flickr User Gemma Zoey (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

—

Dr. Todd Craig is a native of Queens, New York: a product of Ravenswood and Queensbridge Houses in Long Island City. He is a writer, educator and DJ whose career meshes his love of writing, teaching and music. Craig’s research examines the hip-hop DJ as twenty-first century new media reader and writer, and investigates the modes and practices of the DJ as creating the discursive elements of DJ rhetoric and literacy. Craig’s publications include the multimodal novel tor’cha, a short story in Staten Island Noir and essays in textbooks and scholarly journals including Across Cultures: A Reader for Writers, Fiction International, Radical Teacher and Modern Language Studies. He was guest editor of Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education for the special issue “Straight Outta English” (2017). Craig is currently working on his full-length manuscript entitled “K for the Way”: DJ Literacy and Rhetoric for Comp 2.0 and Beyond. Dr. Craig has taught English Composition within the City University of New York for over fifteen years. Presently, Craig is an Associate Professor of English at Medgar Evers College, where he serves as the Composition Coordinator and City University of New York Writing Discipline Council co-chair.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Sounds of Anti-Anti-Essentialism: Listening to Black Consciousness in the Classroom- Carter Mathes

Making His Story Their Story: Teaching Hamilton at a Minority-serving Institution–Erika Gisela Abad

Deejaying her Listening: Learning through Life Stories of Human Rights Violations– Emmanuelle Sonntag and Bronwen Low

Audio Culture Studies: Scaffolding a Sequence of Assignments– Jentery Sayers

Deep Listening as Philogynoir: Playlists, Black Girl Idiom, and Love–Shakira Holt

In his autobiography, Beneath the Underdog, jazz musician Charles Mingus recounts his hatred of being ignored during his bass solos. When it was finally his turn to enter the foreground, suddenly musicians and audience members alike found drinks, food, conversations, and everything else more important. However, this small, and somewhat ironic, anecdote of Mingus’s relationship with the jazz community has now become a foreshadowing of his current status in sound studies–but no longer! This series–featuring myself (Earl Brooks), Brittnay Proctor, Jessica Teague, and Nichole Rustin-Paschal— re/hears, re/sounds and re/mixes the contributions of Mingus for his ingenious approach to jazz performance and composition as well as his far-reaching theorizations of sound in relation to liberation and social equality, all in honor of the 60th anniversary of Mingus’s sublimely idiosyncratic album Mingus Ah Um this month. The final installment of this series presents Nichole Rustin-Paschal and her gripping reflection on jazz, death, and mourning. Her opening line requires no introduction: “There was a time when I believed that Mingus was haunting me.” You can catch up with the full series by clicking

In his autobiography, Beneath the Underdog, jazz musician Charles Mingus recounts his hatred of being ignored during his bass solos. When it was finally his turn to enter the foreground, suddenly musicians and audience members alike found drinks, food, conversations, and everything else more important. However, this small, and somewhat ironic, anecdote of Mingus’s relationship with the jazz community has now become a foreshadowing of his current status in sound studies–but no longer! This series–featuring myself (Earl Brooks), Brittnay Proctor, Jessica Teague, and Nichole Rustin-Paschal— re/hears, re/sounds and re/mixes the contributions of Mingus for his ingenious approach to jazz performance and composition as well as his far-reaching theorizations of sound in relation to liberation and social equality, all in honor of the 60th anniversary of Mingus’s sublimely idiosyncratic album Mingus Ah Um this month. The final installment of this series presents Nichole Rustin-Paschal and her gripping reflection on jazz, death, and mourning. Her opening line requires no introduction: “There was a time when I believed that Mingus was haunting me.” You can catch up with the full series by clicking

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig: