“From where did you receive/research/develop your beliefs? The internet, of course.” -Brenton Tarrant

On Friday, March 15th 2019, at 1:40pm, Brenton Tarrant walked into the first of two mosques in central Christchurch and began shooting indiscriminately, leading to the deaths of 50 people. Already there has been speculation about what drove such an attack. For one writer, Tarrant was clearly inspired by French anti-immigrationist rhetoric. After all, the title of his manifesto, “The Great Replacement,” comes from the book by Renaud Camus, a text cited frequently by far-right politicians like Geert Wilders and the more elusive identitarian movement; while visiting France, Tarrant wrote: “I found my emotions swinging between fuming rage and suffocating despair at the indignity of the invasion of France.”[1] But then there is also the reference to Norwegian mass-murderer Anders Breivik. In his manifesto, Tarrant himself said he “only really took inspiration from Knight Justiciar Breivik.” There are certainly parallels between the self-radicalization of Breivik, a man who increasingly isolated himself physically and emotionally, and the path taken by Tarrant.[2] Yet Tarrant didn’t have to look at the other side of the world for white supremacism. Christchurch has long attempted to shrug off its label as a racist city, one fueled in part by its latent skinhead culture.[3] Such culture breeds mainly underground, but flares up occasionally in violent outbursts in the city and elsewhere: the killing of a council worker in 1989, a Korean backpacker in 2003,[4] an older gay man in 2014.[5] Some speculate that another local influence was the Bruce Rifle Club that Tarrant joined in 2018. One visitor to the club described the members as survivalists and eccentrics who shared “homicidal fantasies” like the zombie apocalypse, and boasted that their guns would only ever be pried “from their cold dead hands.”[6]

Racist writing and racist killers, radical ideologies and gun culture. Yet alongside these traditional inspirations are two new contenders: the dark web and social media. “The Dark Web Enabled the Christchurch Killer” claims one Foreign Policy article. Shortly before beginning his attack, Tarrant posted one final time to the imageboard site 8chan: “Well lads, it’s time to stop shitposting and time to make a real life effort post.” 8chan emerged in 2013 after its creator became disillusioned with the increasingly “authoritarian” culture of 4chan and created this “free-speech-friendly” version in response. Though the site’s Terms of Use prohibit anything explicitly illegal, the unrestricted nature of 8chan means that topics like child rape can surface, or that children in provocative poses can appear.[7] Such appearances are pounced on by the mainstream media. 8chan is invariably described as a “cesspool” and the “gutter of the internet.” In this framing, 8chan is tasteless, degraded, a magnet for the obnoxious and the sociopathic. This is not to defend the site—after scrolling through some of the pages set up to honor Tarrant, the site’s graphic, gleeful screeds are indefensible—but simply to point out the marginalisation enacted by this rhetoric. Despite being publicly accessible like any other website and containing links to hundreds of external sites, 8chan is carefully isolated by labeling it as the “dark web,” a specialist haven for vile and disgusting people and their vile and disgusting ideas.

Others object, stating that social media was the real culprit. Tarrant livestreamed 17 minutes of the shootings on Facebook. He also posted links to his 74-page manifesto on Twitter. Both platforms are designed, as their promotional copy suggests, to “grow your audience”—to allow ideas and events to move beyond an individual’s immediate circle and spread quickly, irrespective of international borders. Global reach is even more important in a geographically isolated country like New Zealand. In the quest for a motivator, the livestream in particular seems to offer a powerful set of forces in a neat package: the opportunity for the perpetrator to star in his own movie with an international horde of onlookers taking in every move. For a brief moment, the world would be forced to turn to Brenton Tarrant, gazing in horror as each moment was captured by a helmet camera, transmitted to Facebook’s servers, and distributed to viewers around the world. Such a view resonates with the now traditional critique of social media as narcissistic. Self-obsessed, we take the craving for views, likes, and comments to the logical extreme, becoming willing to do anything to ratchet up the metrics quantified so precisely by these platforms. There’s no question that the distribution mechanisms enabled by Facebook Live and Twitter helped Tarrant’s videos and writings to spread. Even after Tarrant’s stream was halted, versions of the video continued to circulate widely, despite content monitoring efforts.[8] As one was taken down, others quickly arose to take its place, slipping from user to user, account to account. But Tarrant doesn’t conform to the egotistic social media user, building up an empire to the self. In his own manifesto, he claims that he was not the type to seek fame: “I will be forgotten quickly. Which I do not mind. After all I am a private and mostly introverted person.”

Both the dark web and social media, then, while containing important elements, seem inadequate on their own. These supposedly separate spheres appear to be merging, feeding off each other to form a cohesive online environment. I suggest, then, that Tarrant was encompassed by a seamless blend of recommended racist content and memetically racist humans—a dark social web.

We are only just beginning to learn how dark social media can become. Key to this dark journey are the technical affordances built into these platforms. On social media, one thing leads to another, automatically and effortlessly. Consume content, and similar content will slide into place surrounding it. Such content is built up from our extensive online history: what we watched and commented on, who we followed or subscribed to. Based on these hundreds of signals, we are presented with content that is attractive by design: hooking into our interests, goals and beliefs. In other words, highly individualized content resonates harmoniously with our worldview.

Published back in 2011, Eli Pariser’s book, The Filter Bubble presciently captured this condition where personalized content creates an echo chamber. But Pariser seemed mainly concerned with the bifurcation of politics into left and right, lamenting the erasure of any middle ground between Democrat and Republican, the lack of dialogue between opposing views. What Tarrant epitomizes—and a growing alt-right culture confirms—is that filter bubbles not only reinforce existing views, but amplify them and generate new ones. Users can be nudged from a middle-ground position (whatever that might be) towards something more right leaning, and then from right to far-right. Social media filters are not static entities, based on some fixed notion of our true self, but rather highly dynamic and updated in real-time. As Zeynep Tufekci observes, in serving up more—and more intense—content, these recommendations are “the computational exploitation of a natural human desire: to look ‘behind the curtain,’ to dig deeper into something that engages us.”[9] Your profile incorporates your history, but also whatever you just watched.

Our bubble of personalized information, then, is constantly shifting. And this environment can quickly become darker, piggybacking on what Rebecca Lewis calls the “Alternative Influence Network”: watch comedian/pundit Dave Rubin and a user is recommended his former guest Jordan Peterson; after that a related video might appear from Carl Benjamin, who came to fame through Gamergate; and from there it’s an easy slide into content by Lauren Southern, who was barred from entering England for her anti-Islam activism.[10] The efficacy of this mechanism stems from its automated speed. Every view calculates a new set of recommendations, and yet the time of considering options, weighing the consequences, and making a choice is annihilated altogether. A decision is made without the appearance of decision-making, an influence that seems unbiased and impartial.

As social media grows darker, the dark web grows more social. Sites like 8chan, as mentioned, have been dismissed as the lewd underbelly of the internet, a lonely destination site visited only by the pathologic. Yet if the content posted to these boards is indeed horrific, it is subsumed by the social act of posting. Call and response, meme and countermeme—in this context, posting is just a means to an end, part of a larger meta-game played for lulz. Indeed if there are any “values” left in these spaces that denounce “moralfags,” it is the validation achieved when an image attains traction and is transformed into meme-proper, becoming replicated, shared, and adapted.

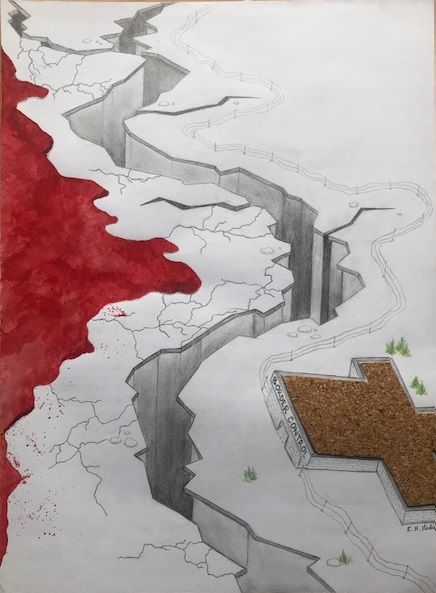

Image boards were never about communication, but about replication. If automated speed was key to social media, memetic speed is critical here. There is no time for discourse in the sense of a considered exchange of ideas. The picture and slogan that gets pasted more, that floods the board, that soaks up more scroll time, wins. Image. Image. Image. The resulting deluge of content desensitizes. The first time a racial slur is encountered, it is shocking. The second time, the visceral disgust has been tempered. The third time, it is abhorrent but expected. And so on. It is not as if the dark web becomes brighter. But the sheer repetition of key terms and images, matched with the enormous volume of posts, becomes numbing. Skimming through the hundreds of posts, one could imagine how the mind of someone already predisposed to extremist views might rapidly adjust. As Tarrant himself observed: “Memes have done more for the ethnonationalist movement than any manifesto.” The shock cannot be sustained; a new normal takes its place.

At a broader level, the so-called dark web becomes socialized through the mainstreaming of platforms. Reddit’s early days, as long-time users can attest, featured child porn, sexual assault, and slavery stories as well as frontpage articles that provoked death and rape threats.[11] Yet over the years, Reddit has been cleaned up through content moderation and is now highly visited, shifting from loser nerd sanctum to heavyweight news nexus. “Reddit has become, simply put, mainstream media,” stressed an AdAge article, noting that, even back then in 2012, it was racking up 400 million unique visitors per month.[12] Purchased by media behemoth Condé Nast, it courts advertisers through sponsored content as well as more organic collaborations like its popular AMA (Ask Me Anything) feature.

Even 4chan has formalized its moderation in order to retain users. Once known as the “asshole of the internet,” the site implemented tools in 2013 to assist its so-called janitors with moderation. These “straightforward and well-intentioned” guidelines, as 4chan’s creator writes, are not meant to “stifle discussion, but to facilitate it.”[13] From 2015 onwards, moderators are asked to sign a legal agreement disclosing their identities and detailing their rights and responsibilities.[14] While not producing cleaner content per se, these measures at least attempt to temper vitriol between users. Yet as discussed, even this moderation is viewed by some as supporting an authoritarian culture of censorship and political correctness, leading to the creation of alternatives like Gab and 8chan. Hard to believe a few years ago, these far-right “havens” for free-speech push 4chan towards a position, that, while certainly not mainstream, is less of an outlier. New extremes emerge; old extremes become normalized. These changes “fill in” the former gaps of ideological terrain, providing more gradual waypoints along an extremist journey.

So rather than the shining beacon of social media and the isolated cesspool of the dark web, we see a dark social web—a smoothly gradated space capable of nudging users towards a far right position. Key here is the notion of seamlessness. Accounts of terror sometimes mention a turning point, a decisive moment when radicalisation occured. But in these technical environments, there is no sign indicating the switch from one ideology to another, no distinctive jolt when transitioning to the next waypoint in this process. The next video autoplays. The next comment is shown. The next site is recommended. As social content gets darker and dark content more social, we witness an algorithmic racism able to select a non-confrontational path through this media and steer the user down it. Based on the rules of recommendations, each piece of content must be familiar, suggested by a user’s previous history, but also novel, something not yet consumed. Calibrated correctly, platforms grasp the social, cultural or ideological connections between content, presenting a sequence of ideas that seem natural, even inevitable. These links, as Lewis argues, make “it easy for audience members to be incrementally exposed to, and come to trust, ever more extremist political positions.”[15]

The dark social web is complex but cohesive. One report states that Tarrant “traveled the world, but lived on the internet.”[16] Meticulously constructed from his extensive internet activity, Tarrant’s online environment corresponded perfectly with his ideology—a world that matched his worldview. It’s easy to imagine him sliding seamlessly between YouTube and 8chan or tabbing from Twitter to Gab without any sense of cognitive dissonance. And yet these all-encompassing environments encompass a kaleidoscope of connected figures, memes and causes. In this world, Gamergate vids blur into mens-rights tweets, SJW jibes merge into classical liberal lectures, and Pepe memes shade quickly into anti-Semitic rants. This suggests, contrary to the claims made by journalists, that the hunt for a definitive influence is a fruitless one. There was no primary motivator for Tarrant to carry out his attacks, no single driver that radicalized him. “From where did you receive/research/develop your beliefs?” asks Tarrant in his FAQ style manifesto. “The internet, of course,” he answers, “over a great deal of time, from a great deal of places.”

Instead what emerges is a kind of algorithmic hate—a constellation of loosely connected digital media, experienced over years, that constructs an algorithmically averaged enemy. Indeed Tarrant’s manifesto is almost boilerplate in its phrasing: faceless “invaders” with high fertility rates who attempt to colonize the “homelands” of the white peoples. While the history of white supremacism should not be underplayed, our contemporary condition tends to politicize through antagonism—what you are against, rather than what you stand for. Algorithmic hate constantly reproduces an “us” versus “them” relation, but who exactly is constituted by “them” is always indistinct. The figure of the Other is impressionistic and hazy, a composite formed from millions of data points. In a sense, Tarrant never really lived in New Zealand; to do so would mean real social encounter, a risk of swapping his faceless adversaries with the flesh-and-blood communities that call Aotearoa home.

Let’s examine some bridging mechanisms of the dark social web. Tarrant stated: “remember lads, subscribe to PewDiePie” just before commencing his shooting spree.[17] In one sense, mentioning the YouTube star was a red herring, a bait for hand-wringing pundits and tech-challenged journalists. The vlogger was no more responsible for the shooting than any other singular actor. But in another sense, the Swedish star provides a useful archetype for understanding how darker racist, sexist, and xenophobic traits can be drawn together with a lighter, socialized whole.

Recommendations provide one method of convergence. Like the “alternative influence network” discussed above, PewDiePie provides a linking mechanism to prominent alt-right figureheads. As one poster points out, he follows Lauren Southern and Stefan Molyneux on Twitter; he endorses Jordan Peterson; and he has hosted Ben Shapiro.[18] Whether these recommendations are done verbally in a video, or occur through automated mechanisms like “suggested for you,” they draw together the hugely successful social icon and the darker ideologies of the alt-right—the popular and the populist. In doing so, they provide a set of natural stepping stones, assisting his massive fan base in a transition to a more extremist position while legitimating it as normal.

Gaming provides another bridge. PewDiePie came to fame initially through his Let’s Plays of horror videogames. While his content these days is broader, he still retains strong links to gaming and gamer culture. Hasan Piker unravels the connections between the vlogger and extremist positions in a video titled: “PewDiePie: Alt-Right or Irresponsible Gamer Bro?”[19] Yet while Piker’s take is thoughtful, it should be clear by now that alt-right and gamer bro are not mutually exclusive categories, but rather heavily overlapping cultures. Indeed one of the core germination points for the modern alt-right was the GamerGate controversy and its associated anti-feminist, anti-SJW rhetoric. “Games were simply the tip of the iceberg – progressive values, went the argument, were destroying everything.”[20] Paradoxically, by clinging to the “norm” in the face of “libtard invaders,” Gamergate and its offshoots steered a core group of disaffected young white men into a far-right position.

Irony provides the final link. PewDiePie is no stranger to controversy. This is a man who has hired men to carry a “death to all Jews” sign, who has used the n-word in one stream, and who has called a female streamer a “crybaby and an idiot” for demanding equal pay.[21] These actions have led to criticism and contracts being terminated. But the streamer is also affable and funny, emanating a care-free attitude. He is the perfect conduit for the “ironic racism” employed in heavy doses by alt-right advocates. In the meme-saturated environment of social media, irony provides plausible deniability. It’s a comedy channel. It was obviously a joke. Quit being overly sensitive. Late last year, Pewdiepie recommended the “E;R” channel, which happens to feature Nazi propaganda behind a thin veneer of humour. When the channel creator was asked if he “redpilled,” or tried to convince viewers of their white superiority, he responded: “Pretend to joke about it until the punchline /really/ lands.”

Pewdiepie thus displays some of the ways in which social media and the dark web converge to form an environment conducive to alt-right ideals. But again, the YouTube star is simply a proxy, the most obvious example of a more general capability. The nodes for others will be different; their paths to extremism will be uniquely theirs. One of the strengths of the dark social web is that is highly individualized, an environment algorithmically optimized to reflect its inhabitant. The path that Brenton Tarrant took is not yet fully known, and the online environment he was surrounded in is open to speculation. Yet in an operational sense, Tarrant’s environment of platforms, sites and services is exactly the same as ours—it is designed in the same way, with the same architectures and affordances. Strangely, as the alt-right proliferates and the far-right secures yet another parliamentary win, it seems as if we’re only just waking up to the dark capabilities—socially, culturally, and politically—that these environments enable. After all, fascism is not congenital; nor is evil innate. Instead, if we are a product of our environment, then we need to seriously investigate the sociotechnical properties of that environment. Failure to do so could result in the next generation following in the footsteps of Brenton Tarrant.

—

Based in Aotearoa New Zealand, Luke Munn uses both practice-based and theoretical approaches to explore the intersections of digital cultures. He has recently completed a PhD on algorithmic power at Western Sydney University.

[11] https://www.reddit.com/r/AskReddit/comments/724a47/what_dark_part_of_reddit_history_has_been/

[17] In fact “Subscribe to PewDiePie” is not just a generic request but a meme referencing the online campaign to keep Felix Kjellberg as the #1 subscribed-to channel on YouTube. His challenger was the T-Series channel, a company that according to PewDiePie fans, “simply uploads trailers of Bollywood videos and songs.” Already then, race quietly emerges in the war between the white, Swedish Kjellberg and the Indian managed T-series.

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

When times are tough and people are feeling sad, they might need space to be calm, to reflect, and to heal. For example, in the United States following September 11, 2001, Clear Channel (now iHeartMedia)

When times are tough and people are feeling sad, they might need space to be calm, to reflect, and to heal. For example, in the United States following September 11, 2001, Clear Channel (now iHeartMedia) Hiromu Nagahara is a historian who has examined how music was used during a transformative era in Japanese history. Nagahara’s book,

Hiromu Nagahara is a historian who has examined how music was used during a transformative era in Japanese history. Nagahara’s book,

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Is literature truly a primarily visual entity? Do we only read books or are we actually actively

Is literature truly a primarily visual entity? Do we only read books or are we actually actively  Furlonge, previously chair of the English Department at the Princeston Day School, and new Director of

Furlonge, previously chair of the English Department at the Princeston Day School, and new Director of

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig: