In “Asesina,” Darell opens the track shouting “Everybody go to the discotek,” a call for listeners to respond to the catchy beat and come dance. In this series on rap in Spanish and Sound Studies, we’re calling you out to the dance floor…and we have plenty to say about it. Your playlist will not sound the same after we’re through.

In “Asesina,” Darell opens the track shouting “Everybody go to the discotek,” a call for listeners to respond to the catchy beat and come dance. In this series on rap in Spanish and Sound Studies, we’re calling you out to the dance floor…and we have plenty to say about it. Your playlist will not sound the same after we’re through.

Throughout January, we will explore what Spanish rap has to say on the dance floor, in our cars, and through our headsets. We’ll read about Latinx beats in Australian clubs, and about femme sexuality in Cardi B’s music. And because no forum on Spanish rap is complete without a mixtape, we’ll close out our forum with a free playlist for our readers. Today we start No Pare, Sigue Sigue: Spanish Rap & sound Studies with Michael Levine’s essay on Trap cubano and el paquete semanal.

-Liana M. Silva, forum editor

—

Trap Latino has grown popular in Cuba over the past few years. Listen to the speakers blaring from a young passerby’s cellphone on Calle G, or scan through the latest digital edition of el paquete semanal (the weekly package), and you are bound to hear the genre’s trademark 808 bass boom in full effect. The style however, is almost entirely absent from state radio, television, and concert venues. To the Cuban state (and many Cubans), the supposed musical and lyrical values expressed in the music are unacceptable for public consumption. Like reggaetón a decade before, the reputation of Trap Latino (and especially the homegrown version, Trap Cubano) intersects with contemporary debates regarding the future of Cuba’s national project. For many of its fans however, the style’s ability to challenge the narratives of the Cuban state is precisely what makes Trap Latino so appealing.

In an article published last year by Granma (Cuba’s official, state-run media source), Havana-based journalist Guillermo Carmona positions Trap Latino artists like Bad Bunny and Bryant Myers as a negative influence on Cuba’s youth, claiming the music sneaks its way into the ears of unsuspecting Cuban youth via the illicit channels of Cuba’s underground internet. With lyrics that celebrate the drug trade and treat women as “slot machines,” coupled with a preponderance of sound effects instead of “music notes,” Carmona considers Trap Latino aggressive, dangerous, and perhaps most perniciously of all, irredeemably foreign.

Towards the end of the article, Carmona focuses on his biggest concern: the performance of Trap Latino in public spaces. Carmona writes of those who play Trap from sound systems that “…they use portable speakers and walk through the streets (dangerously), like a baby driving a car. The combat between the bands that narrate some of these songs gestures towards another battlefield: the public sound space.” For Carmona, this public battlefield is sonically marked by Trap Latino’s encroachment on Cuba’s hallowed musical turf. His complaints highlight the fact that this Afro-Latinx style largely exists in Cuba on one side of what Jennifer Lynn Stoever refers to as the sonic color line, an “interpretive and socially constructed practice conditioned by historically contingent and culturally specific value systems riven with power relations” (14).

In Cuba, historically constructed power relations are responsible for much of the public reception of Afro-Cuban popular music, including rumba, timba, and reggaetón. But Trap Latino’s growing presence on the digital devices of Cuban youth is reshaping the boundaries of Cuba’s sonic color line. While these traperos are generally unable to perform in public (due to strict laws governing uses of Cuba’s public spaces) their music is nonetheless found across Havana’s urban soundscape, thanks to the illicit, but widespread, distribution of the “Cuban Internet.”Historically marginalized Afro-Cuban artists, like Alex Duvall, are today using creative digital strategies to make their music heard in ways that were impossible just a decade ago.

The Cuban Internet

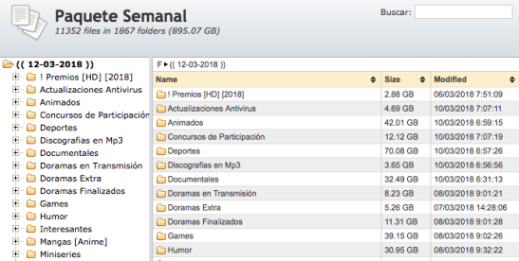

To get around the lack of an internet infrastructure either too costly, or too difficult to access, Cubans have developed a network for trading digital media referred to as “el paquete semanal,” contained on terabyte-sized USB memory sticks sold weekly to Cuban residents. These memory sticks contain plenty of content: movies, music, software applications, a “Craiglist”-styled bulletin board of local products for sale, and even an offline social network, among others. The device is traded surreptitiously, presumably without the knowledge of the state.

(There is some question surrounding the degree at which the state is unaware of the paquete trade. Robin Moore, in Music and Revolution, refers to the Cuban government’s propensity to selectively enforce certain illegalities as “lowered frequency”. Ex-president Raul Castro has publicly referred to the device as a ‘necessary evil,” suggesting knowledge, and tacit acceptance, of the device’s circulation.)

By providing a means for artists to circulate products outside of state-sanctioned channels of distribution, el paquete semanal greatly broadens the range of content available to the Cuban public. The importance of the paquete to Cuba’s youth cannot be overstated. According to Havana-based journalist José Raúl Concepción, over 40% of Cuban households consume the paquete on a weekly basis, and over 80% of citizens under the age of 21 consume the paquete daily. A high percentage of the music contained on these devices is not played on the radio or seen in live concerts. For many Cubans, it is only found in the folders contained on these devices. The paquete trade therefore, serves as an invaluable barometer of music trends, especially those of younger people who represent the largest number of consumers of the device.

A listing of folders on el paquete semanal from October 30, 2018.

Alex Duvall

There is a random-access, mix-tape quality to the paquete that encourages consumers to discover music by loading songs onto their cellphones, shuffling the contents, and pressing play (a practice as common in Cuba as it is in the US). This mode of consumption encourages listeners to discover music to which they otherwise would not be exposed. Reggaetón/Trap Latino artist Alex Duvall takes advantage of this organizing structure to promote his work in a unique manner: Duvall packages his reggaetón music separately from his Trap Latino releases. As a solo act, his reggaetón albums position catchy dembow rhythms alongside lyrics and videos that celebrate love of nation, Cuban women, and Havana’s historic landmarks. As a Trap Latino artist in the band “Trece,” his brand is positioned quite differently. Music videos like Trece’s “Mi Estilo de Vida” for instance, contain many of the markers that journalist Guillermo Carmona criticized in the aforementioned article: a range of women wear the band’s name on bandanas covering their faces, otherwise leaving the rest of their bodies exposed. US currency floats in mid-air, and lyrics address the pleasures of material comforts amid legally questionable ways of “making it.”

Especially as it becomes more and more common for Latinx artists to mix genres freely together in their music (as the catch-all genre format referred to as música urbana shows), it is significant that Alex Duvall prefers to keep these styles separate in his own work. The strategy reveals a musical divide between foreign and domestic elements. Duvall’s reggaetón releases emphasize percussive effects, and the Caribbean-based “dembow riddim” that many Cubans would quickly recognize. The synthesized elements in his Trap Latino work however, belong to an aesthetic foreign to historic representations of Cuban music, representing broader circulations of sound that now extend up to the US. Textures and rhythms originating from Atlanta (along with their attendant political and historical baggage) now share space in the sonic palette of a popular Cuban artist.

Going to the Rumba

These cultural circulations complicate narratives coming from the Cuban state that tend to minimize the cultural impact of music originating from the yankui neighbor to the north. These narratives exert powerful political pressure. Because of this, artists are careful when describing their involvement with Trap music. Duvall’s digital strategy allows for a degree of freedom in traveling back and forth across the sonic color line, but permits only so much mobility.

In an interview conducted by MiHabanaTV, Duvall distances himself from Trap Latino’s reputation, defending his project by appealing to the genre’s international popularity, and the need to bring it home to Cuba. But the 2017 song “Hasta La Mañana” documents one of his most concise explanations for his involvement in Trece, in the following lyrics:

| “El tiempo va atando billetes a cien Pero todos va para la rumba Entonces yo quiero sumarme tambien.” |

Time is tying hundred dollar bills together Everyone is going to the rumba And I also want to join. |

He uses “rumba” here as shorthand to refer to the subversive actions that people take in order to succeed in difficult situations. Duvall needs to make money. If everyone else gets rich by going to “the rumba,” why can’t he? The reference is revealing. Rumba marks another Afro-Cuban tradition with a history of marginalized figures engaged in debates over appropriate aural uses of public space. Today, cellphone speakers and boom boxes sound Havana’s parks and streets. Historically, Afro-Cuban rumberos made these spaces audible through live performance, but similar issues of race animate both of these moments.

In the essay “Walking,” sociologist Lisa Maya Knauer explains that it was not uncommon for police to break up a rumba being performed in the streets or someone’s home throughout the twentieth century “on the grounds that it was too disruptive.” (153) Knauer states that rumba music is historically associated with “rowdiness, civil disorder, and unbridled sexuality, while simultaneously celebrated as an icon of national identity”. (131) The quote also reveals a contrast between the public receptions of rumba and Trap Latino. Duvall’s work, and Trap Latino more generally, is similarly fixed amid a complex web of racialized associations. But unlike rumba, refuses to appeal to state-sanctioned ideals of national identity.

Afro-Cuban musicians are often pressured to adopt nationally sanctioned modes of participation in order to acquire official recognition and state funding. The acceptable display of blackness in Cuba’s public spaces, especially while performing for the country’s growing number of tourists, is a process that anthropologist Marc D. Perry calls the “buenavistization” of Cuba in his work Negro Soy Yo. This phrase refers to the success of popular Son heritage group Buena Vista Social Club, and the revival of Afro-Cuban heritage musical styles that this group and its associated film popularized. Unlike Rumba and Son however, Trap Latino is considered irredeemably foreign (given its roots in both the US city of Atlanta and later, Puerto Rico), therefore presenting difficulties in assimilating the genre to dominant models of Cuban national identity. This tension, I believe, is also responsible for it’s success among Cuba’s youth.

Trap Cubano’s growing appeal stems instead from artists’ adoption of a radically counter-cultural positionality often avoided in popular contemporary styles like reggaetón. While it would be unfair to accuse reggaetón as being entirely co-opted (a point musicologist Geoff Baker makes convincingly in “Cuba Rebelión: Underground Music in Havana”), it is certainly true that as reggaetóneros achieve greater success in ever widening circles of international popularity, the amount of scandalized lyrics, eroticized imagery, and the sound of the original dembow riddim itself (with its well documented roots in homophobia and virulent masculinity) has diminished considerably. Trap Latino’s sonic subversions fill this gap. While the genre similarly praises the fulfillment of male, material fantasies, it troubles the narrative that increased access to money solves social, racial, and gender imbalances, while sonically acknowledging the role that the US shares in shaping it’s musical terrain.

This centering of materialism amid representations of marginalized Afro-Cuban artists is foreign to both historic and touristic representations of Cuba, but relevant to a younger generation increasingly confronted with the pressures of encroaching capitalism. Trap Cubano renders visible (and audible) an emerging culture managing life on the less privileged side of the sonic color line. From the speakers blaring from a young passerby’s cellphone on Calle G, to the USB stick plugged in to a blaring sound system, to the rumba where Alex Duvall is headed, Trap Latino broadcasts the concerns of a younger generation challenging what it means to be Cuban in the 21st century, and what that future sounds like.

—

Involving himself in the music scenes of Brooklyn, N.Y. over the past decade, Mike Levine has utilized a dual background in academic research and web-based application technologies to support sustainable local music scenes. His research now takes him to Cuba, where he studies the artists and fans circulating music in this vibrant and fast-changing space via Havana’s USB-based, ‘people-powered’ internet (el paquete semanal) amidst challenging political and economic circumstances.

—

Featured image: “Hotel Cohiba – Havana, Cuba” by Flickr user Chris Goldberg, CC BY-NC 2.0

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Spaces of Sounds: The Peoples of the African Diaspora and Protest in the United States–Vanessa Valdes

SO! Reads: Shana Redmond’s Anthem: Social Movements and the Sound of Solidarity in the African Diaspora–Ashon Crawley

Music Meant to Make You Move: Considering the Aural Kinesthetic– Imani Kai Johnson

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig: