“How Many Latinos are in this Motherfucking House?”: DJ Irene, Sonic Interpellations of Dissent and Queer Latinidad in ’90s Los Angeles

How Many Latinos are in this Motherfucking House? –DJ Irene

At the Arena Nightclub in Hollywood, California, the sounds of DJ Irene could be heard on any given Friday in the 1990s. Arena, a 4000-foot former ice factory, was a haven for club kids, ravers, rebels, kids from LA exurbs, youth of color, and drag queens throughout the 1990s and 2000s. The now-defunct nightclub was one of my hang outs when I was coming of age. Like other Latinx youth who came into their own at Arena, I remember fondly the fashion, the music, the drama, and the freedom. It was a home away from home. Many of us were underage, and this was one of the only clubs that would let us in.

Arena was a cacophony of sounds that were part of the multi-sensorial experience of going to the club. There would be deep house or hip-hop music blasting from the cars in the parking lot, and then, once inside: the stomping of feet, the sirens, the whistles, the Arena clap—when dancers would clap fast and in unison—and of course the remixes and the shout outs and laughter of DJ Irene, particularly her trademark call and response: “How Many Motherfucking Latinos are in this Motherfucking House?,” immortalized now on CDs and You-Tube videos.

DJ Irene

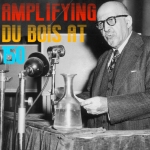

Irene M. Gutierrez, famously known as DJ Irene, is one of the most successful queer Latina DJs and she was a staple at Arena. Growing up in Montebello, a city in the southeast region of LA county, Irene overcame a difficult childhood, homelessness, and addiction to break through a male-dominated industry and become an award-winning, internationally-known DJ. A single mother who started her career at Circus and then Arena, Irene was named as one of the “twenty greatest gay DJs of all time” by THUMP in 2014, along with Chicago house music godfather, Frankie Knuckles. Since her Arena days, DJ Irene has performed all over the world and has returned to school and received a master’s degree. In addition to continuing to DJ festivals and clubs, she is currently a music instructor at various colleges in Los Angeles. Speaking to her relevance, Nightclub&Bar music industry website reports, “her DJ and life dramas played out publicly on the dance floor and through her performing. This only made people love her more and helped her to see how she could give back by leading a positive life through music.”

DJ Irene’s shout-out– one of the most recognizable sounds from Arena–was a familiar Friday night hailing that interpellated us, a shout out that rallied the crowd, and a rhetorical question. The club-goers were usually and regularly predominately Latin@, although other kids of color and white kids also attended. We were celebrating queer brown life, desire, love in the midst of much suffering outside the walls of the club like anti-immigrant sentiment, conservative backlash against Latinos, HIV and AIDS, intertwined with teen depression and substance abuse.

From my vantage today, I hear the traces of Arena’s sounds as embodied forms of knowledge about a queer past which has become trivialized or erased in both mainstream narratives of Los Angeles and queer histories of the city. I argue that the sonic memories of Arena–in particular Irene’s sets and shout outs–provide a rich archive of queer Latinx life. After the physical site of memories are torn down (Arena was demolished in 2016), our senses serve as a conduit for memories.

As one former patron of Arena recalls, “I remember the lights, the smell, the loud music, and the most interesting people I had ever seen.” As her comment reveals, senses are archival, and they activate memories of transitory and liminal moments in queer LA Latinx histories. DJ Irene’s recognizable shout-out at the beginning of her sets– “How Many Latinos are in this House?”–allowed queer Latinx dancers to be seen and heard in an otherwise hostile historical moment of exclusion and demonization outside the walls of the club. The songs of Arena, in particular, function as a sonic epistemology, inviting readers (and dancers) into a specific world of memories and providing entry into corporeal sites of knowledge.

Both my recollections and the memories of Arena goers whom I have interviewed allow us to register the cultural and political relevance of these sonic epistemologies. Irene’s shout-outs function as what I call “dissident sonic interpolations”: sounds enabling us to be seen, heard, and celebrated in opposition to official narratives of queerness and Latinidad in the 1990s. Following José Anguiano, Dolores Inés Casillas, Yessica García Hernandez, Marci McMahon, Jennifer L. Stoever, Karen Tongson, Deborah R. Vargas, Yvon Bonenfant, and other sound and cultural studies scholars, I argue that the sounds surrounding youth at Arena shaped them as they “listened queerly” to race, gender and sexuality. Maria Chaves-Daza reminds us that “queer listening, takes seriously the power that bodies have to make sounds that reach out of the body to touch queer people and queer people’s ability to feel them.” At Arena, DJ Irene’s vocalic sounds reached us, touching our souls as we danced the night away.

Before you could even see the parade of styles in the parking lot, you could hear Arena and/or feel its pulse. The rhythmic stomping of feet, for example, an influence from African-American stepping, was a popular club movement that brought people together in a collective choreography of Latin@ comunitas and dissent. We felt, heard, and saw these embodied sounds in unison. The sounds of profanity–“motherfucking house”–from a Latina empowered us. Irene’s reference to “the house,” of course, makes spatial and cultural reference to Black culture, house music and drag ball scenes where “houses” were sites of community formation. Some songs that called out to “the house” that DJ Irene, or other DJs might have played were Frank Ski’s “There’s Some Whores in this House,” “In My House” by the Mary Jane Girls, and “In the House” by the LA Dream Team.

Then, the bold and profane language hit our ears and we felt pride hearing a “bad woman” (Alicia Gaspar de Alba) and one of “the girls our mothers warned us about” (Carla Trujillo). By being “bad” “like bad ass bitch,” DJ Irene through her language and corporeality, was refusing to cooperate with patriarchal dictates about what constitutes a “good woman.” Through her DJing and weekly performances at Arena, Irene contested heteronormative histories and “unframed” herself from patriarchal structures. Through her shout outs we too felt “unframed” (Gaspar de Alba).

Dissident sonic interpellation summons queer brown Latinx youth–demonized and made invisible and inaudible in the spatial and cultural politics of 1990s Los Angeles—and ensures they are seen and heard. Adopting Marie “Keta” Miranda’s use of the Althusserian concept of interpellation in her analysis of Chicana youth and mod culture of the 60s, I go beyond the notion that interpellation offers only subjugation through ideological state apparatus, arguing that DJ Irene’s shout-outs politicized the Latinx dancers or “bailadorxs” (Micaela Diaz-Sanchez) at Arena and offered them a collective identity, reassuring the Latinxs she is calling on of their visibility, audibility, and their community cohesiveness.

Perhaps this was the only time these communities heard themselves be named. As Casillas reminds us “sound has power to shape the lived experiences of Latina/o communities” and that for Latinos listening to the radio in Spanish for example, and talking about their situation, was critical. While DJ Irene’s hailing did not take place on the radio but in a club, a similar process was taking place. In my reading, supported by the memories of many who attended, the hailing was a “dissident interpolation” that served as recognition of community cohesiveness and perhaps was the only time these youth heard themselves publicly affirmed, especially due to the racial and political climate of 1990s Los Angeles.

Vintage photo of Arena, 1990s, Image by Julio Z

The 1990s were racially and politically tense time in Los Angeles and in California which were under conservative Republican leadership. At the start of the nineties George Deukmejian was finishing his last term from 1990-1991; Pete Wilson’s tenure was from 1991-1999. Richard Riordan was mayor of Los Angeles for the majority of the decade, from 1993- 2001. The riots that erupted in 1992 after the not guilty verdict for the police officers indicted in the Rodney King beating case and the polarizing effect of the OJ Simpson trial in 1995 were indicative of anti-black and anti-Latinx racism and its impacts across the city. In addition to these tensions, gang warfare and the 1994 earthquake brought on its own set of economic and political circumstances. Anti-immigrant sentiment had been building since the 1980s when economic and political refugees from Mexico and Central American entered the US in large numbers and with the passing of the Immigration Reform and Control Act in 1986, what is known as Reagan’s “Amnesty program.” On a national level, Bill Clinton ushered in the implementation of the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy in the military, which barred openly LGB people from service. In 1991, Anita Hill testified against Clarence Thomas’s nomination to the United States Supreme Court due to his ongoing sexual harassment of her at work; the U.S. Senate ultimately browbeat Hill and ignored her testimony, confirming Thomas anyway.

In the midst of all this, queer and minoritized youth in LA tried to find a place for themselves, finding particular solace in “the motherfucking house”: musical and artistic scenes. The club served a “house” or home to many of us and the lyrical references to houses were invitations into temporary and ephemeral sonic homes. Counting mattered. Who did the counting mattered. How many of us were there mattered. An ongoing unofficial census was unfolding in the club through Irene’s question/shout-out, answered by our collective cheers, whistles, and claps in response. In this case, as Marci McMahon reminds us, “Sound demarcates whose lives matter” (2017, 211) or as the Depeche Mode song goes, “everything counts in large amounts.”

Numbers mattered at a time when anti-immigrant sentiment was rampant, spawning white conservative sponsored legislation such as Prop 187 the so-called “Save Our State” initiative (which banned “undocumented Immigrant Public Benefits”), Prop 209 (the ban on Affirmative Action), and Prop 227 “English in Public Schools” (the Bilingual Education ban). Through these propositions, legislators, business people, and politicians such as Pete Wilson and his ilk demonized our parents and our families. Many can remember Wilson’s virulently anti-immigrant 1994 re-election campaign advertisement depicting people running across the freeway as the voiceover says “They keep coming” and then Wilson saying “enough is enough.” This ad is an example of the images used to represent immigrants as animals, invaders and as dangerous (Otto Santa Ana). As Daniel Martinez HoSang reminds us, these “racial propositions” were a manifestation of race-based hierarchies and reinforced segregation and inequity (2010, 8).

While all of this was happening— attempts to make us invisible, state-sponsored refusals of the humanity of our families—the space of the club, Irene’s interpellation, and the sounds of Arena offered a way to be visible. To be seen and heard was, and remains, political. As Casillas, Stoever, and Anguiano and remind us in their work on the sounds of Spanish language radio, SB 1070 in Arizona, and janitorial laborers in Los Angeles, respectively, to be heard is a sign of being human and to listen collectively is powerful.

Listening collectively to Irene’s shout out was powerful as a proclamation of life and a celebratory interpellation into the space of community, a space where as one participant in my project remembers, “friendships were built.” For DJ Irene to ask how many Latinos were in the house mattered also because the AIDS prevalence among Latinos increased by 130% from 1993 to 2001. This meant our community was experiencing social and physical death. Who stood up, who showed up, and who danced at the club mattered; even though we were very young, some of us and some of the older folks around us were dying. Like the ball culture scene discussed in Marlon M. Bailey’s scholarship or represented in the new FX hit show Pose, the corporeal attendance at these sites was testament to survival but also to the possibility for fabulosity. While invisibility, stigma and death loomed outside of the club, Arena became a space where we mattered.

For Black, brown and other minoritized groups, the space of the queer nightclub provided solace and was an experiment in self-making and self-discovery despite the odds. Madison Moore reminds us that “Fabulousness is an embrace of yourself through style when the world around you is saying you don’t deserve to be here” (New York Times). As Louis Campos–club kid extraordinaire and one half of Arena’s fixtures the Fabulous Wonder Twins–remembers,

besides from the great exposure to dance music, it [Arena] allowed the real-life exposure to several others whom, sadly, became casualties of the AIDS epidemic. The very first people we knew who died of AIDS happened to be some of the people we socialized with at Arena. Those who made it a goal to survive the incurable epidemic continued dancing.

The Fabulous Wonder Twins

Collectively, scholarship by queer of color scholars on queer nightlife allows us entryway into gaps in these queer histories that have been erased or whitewashed by mainstream gay and lesbian historiography. Whether queering reggaetón (Ramón Rivera-Servera), the multi-Latin@ genders and dance moves at San Francisco’s Pan Dulce (Horacio Roque-Ramirez), Kemi Adeyemi’s research on Chicago nightlife and the “mobilization of black sound as a theory and method” in gentrifying neighborhoods, or Luis-Manuel García’s work on the tactility and embodied intimacy of electronic dance music events, these works provide context for Louis’ remark above about the knowledges and affective ties and kinships produced in these spaces, and the importance of nightlife for queer communities of color.

When I interview people about their memories, other Arena clubgoers from this time period recall a certain type of collective listening and response—as in “that’s us! Irene is talking about us! We are being seen and heard!” At Arena, we heard DJ Irene as making subversive aesthetic moves through fashion, sound and gestures; Irene was “misbehaving” unlike the respectable woman she was supposed to be. Another queer Latinx dancer asserts: “I could fuck with gender, wear whatever I wanted, be a puta and I didn’t feel judged.”

DJ Irene’s “How many motherfucking Latinos in the motherfucking house,” or other versions of it, is a sonic accompaniment to and a sign of, queer brown youth misbehaving, and the response of the crowd was an affirmation that we were being recognized as queer and Latin@ youth. For example, J, one queer Chicano whom I interviewed says:

We would be so excited when she would say “How Many Latinos in the Motherfucking House?” Latinidad wasn’t what it is now, you know? There was still shame around our identities. I came from a family and a generation that was shamed for speaking Spanish. We weren’t yet having the conversation about being the majority. Arena spoke to our identities.

For J, Arena was a place that spoke to first generation youth coming of age in LA, whose experiences were different than our parents and to the experiences of queer Latinxs before us. In her shout-outs, DJ Irene was calling into the house those like J and myself, people who felt deviant outside of Arena and/or were then able to more freely perform deviance or defiance within the walls of the club.

Our responses are dissident sonic interpellations in that they refuse the mainstream narrative. If to be a dissident is to be against official policy, then to be sonically dissident is to protest or refuse through the sounds we make or via our response to sounds. In my reading, dissident sonic interpellation is both about Irene’s shout out and about how it moved us towards and through visibility and resistance and about how we, the interpellated, responded kinetically through our dance moves and our own shout outs: screaming, enthusiastic “yeahhhhs,” clapping, and stomping. We were celebrating queer brown life, desire, love in the midst of much suffering outside the walls of the club. Arena enabled us to make sounds of resistance against these violences, sounds that not everyone hears, but as Stoever reminds us, even sounds we cannot all hear are essential, and how we hear them, even more so.

Even though many of us didn’t know Irene personally (although many of the club kids did!) we knew and felt her music and her laughter and the way she interpellated us sonically in all our complexity every Friday. Irene’s laughter and her interpellation of dissent were sounds of celebration and recognition, particularly in a city bent on our erasure, in a state trying to legislate us out of existence, on indigenous land that was first our ancestors.

In the present, listening to these sounds and remembering the way they interpellated us is urgent at a time when gentrification is eliminating physical traces of this queer history, when face-to face personal encounters and community building are being replaced by social media “likes,” and when we are engaging in a historical project that is “lacking in archival footage” to quote Juan Fernandez, who has also written about Arena. When lacking the evidence Fernandez writes, the sonic archive whether as audio recording or as a memory, importantly, becomes a form of footage. When queer life is dependent on what David Eng calls “queer liberalism” or “the empowerment of certain gay and lesbian U.S. citizens economically through an increasingly visible and mass-mediated consumer lifestyle, and politically through the legal protection of rights to privacy and intimacy,” spaces like Arena–accessed via the memories and the sonic archive that remains– becomes ever so critical.

Voice recordings can be echoes of a past that announce and heralds a future of possibility. In their Sounding Out! essay Chaves-Daza writes about her experience listening to a 1991 recording of Gloria Anzaldúa speaking at the University of Arizona, which they encountered in the archives at UT Austin. Reflecting on the impact of Anzaldúa’s recorded voice and laughter as she spoke to a room full of queer folks, Chaves-Daza notes the timbre and tone, the ways Anzaldúa’s voice makes space for queer brown possibility. “Listening to Anzaldúa at home, regenerates my belief in the impossible, in our ability to be in intimate spaces without homophobia,” they write.

Queer Latinxs coming across or queerly listening to Irene’s shout out is similar to Chaves-Daza’s affective connection to Anzaldúa’s recording. Such listening similarly invites us into the memory of the possibility, comfort, complexity we felt at Arena in the nineties, but also a collective futurity gestured in Chaves-Daza’s words:. “Her nervous, silly laugh–echoed in the laughs of her audience–reaches out to bring me into that space, that time. Her smooth, slow and raspy voice–her vocalic body–touches me as I listen.” She writes, “Her voice in the recording and in her writing sparks a recognition and validation of my being.” Here, Anzaldúa’s laughter, like Irene’s shout-out, is a vocal choreography and creates a “somatic bond,” one I also see in other aspects of dancers, bailadorxs, remembering about and through sound and listening to each other’s memories of Arena. Chaves-Daza writes, “sound builds affective connections between myself and other queers of color- strikes a chord in me that resonates without the need for language, across space and time.”

In unearthing these queer Latin@ sonic histories of the city, my hopes are that others listen intently before these spaces disappear but also that we collectively unearth others. At Arena we weren’t just dancing and stomping through history, but we were making history, our bodies sweaty and styled up and our feet in unison with the beats and the music of DJ Irene.“ How Many Latinos in the Mutherfucking House?”, then, as a practice of cultural citizenship, is about affective connections (and what Karen Tongson calls “remote intimacies”), “across, space and time.” The musics and sounds in the archive of Arena activates the refusals, connections, world-making, and embodied knowledge in our somatic archives, powerful fugitive affects that continue to call Latinx divas to the dancefloor, to cheer, stomp and be counted in the motherfucking house: right here, right now.

—

—

Featured Image: DJ Irene, Image by Flickr User Eric Hamilton (CC BY-NC 2.0)

—

Eddy Francisco Alvarez Jr. came of age in the 1990s, raised in North Hollywood, California by his Mexican mother and Cuban father. A a first generation college student, he received his a BA and MA in Spanish from California State University, Northridge and his PhD in Chicana and Chicano Studies from University of California, Santa Barbara. A former grade school teacher, after graduate school, he spent three years teaching Latinx Studies in upstate New York before moving to Oregon where he is an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and University Studies at Portland State University. His scholarly and creative works have been published in TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, Aztlan: A Journal of Chicano Studies, Revista Bilingue/Bilingual Review, and Pedagogy Notebook among other journals, edited books, and blogs. Currently, he is working on a book manuscript titled Finding Sequins in the Rubble: Mapping Queer Latinx Los Angeles. He is on the board of the Association for Jotería Arts, Activism, and Scholarship (AJAAS) and Friends of AfroChicano Press.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

“Music to Grieve and Music to Celebrate: A Dirge for Muñoz”-Johannes Brandis

On Sound and Pleasure: Meditations on the Human Voice-Yvon Bonenfant

Music Meant to Make You Move: Considering the Aural Kinesthetic– Imani Kai Johnson

Black Joy: African Diasporic Religious Expression in Popular Culture–Vanessa Valdés

Unapologetic Paisa Chingona-ness: Listening to Fans’ Sonic Identities–Yessica Garcia Hernandez

On the #MarielleMultiplica Action in Brazil

By Isabel Löfgren (Stockholm)

The October 2018 presidential elections in Brazil saw the rise of an extreme-right candidate due to several strategies, but there are equally many counter-movements that took place in the electoral period.

One of these counter-movements is the action #MarielleMultiplica which went viral after a series of street protests for human rights, democracy and social justice, in response to the openly mysogynistic, racist, and authoritarian rhetorics of the what was to be the winning party, Jair’s Bolsonaro’s PSL.

The #MarielleMultiplica action started in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in October 2018 in preparation for a manifestation in honor of Marielle Franco, a black lesbian sociologist and elected local politician, executed earlier this year in an ambush for her work in the city’s human rights commission. Her task was to report on potential abuses of a military intervention in Rio’s favelas. Marielle Franco became an international symbol for social justice, and we are still wondering #QuemMatouMarielle? – who killed Marielle?

At the time of her death, a symbolic street sign with her name was created as a symbol and homage on the street where she was killed in central Rio.

In commemoration of the 6-month anniversary of her death in mid-October, a manifestation would be held in honor to claim for resolution of the crime and also strengthen the campaign for democracy during the elections. When white male candidates of the extreme-right party PSL learned about this, they took the symbolic street sign in Marielle Franco’s honor, broke it in half in a political rally and held it up like a war trophy as a crowd of thousands of people cheered on. All the candidates who broke Marielle’s street sign on this rally were elected in state elections for high posts in the senate, chamber of deputies and as the governor of the state, with a very high number of votes.

The response by an online satirical newspaper Sensacionalista with a crowdfunding initiative to print 1,000 signs and give the proceeds for a human rights organization. These signs were distributed on site in Cinelândia, where the manifestation took place. An online arts platform (Caju.com.br) run by curator Daniela Name and artist Sidnei Balbino printed out 2,000 more signs for the occasion, which was already scheduled when the original street sign was torn apart.

The manifestation was held with over 30,000 people on the streets of Rio. The 3,000 street signs were then placed everywhere in the city, hashtagged #MarielleMultiplica online. Celebrities joined in and helped the cause onsite and online. The artist received orders for more prints as the action went viral. Other cities in Brazil printed signs and did similar manifestations. The street sign now has been printed 13,000 times, and spread all over Brazil and in the world.

As the manifestation hit social media (mass media reported very little on this), the street sign went viral with the hashtag #MarielleMultiplica – “Marielle Multiplied”.

I took part of this action remotely by requesting the design to be printed in Stockholm. 20 such signs were printed and spread in the city. It was also sent to other Brazilians abroad to do the same. On election day, October 28th, a group of Brazilian women and I placed the street sign on the Brazilian Embassy wall. This was further photographed and viralized in social media.

Marielle Franco’s memory cannot be torn apart by fascist politicians. Her memory will multiply until justice will be done.

Below some images of the political rally where the sign was broken, and the response/action/manifestation in Brazil, Stockholm and other places in the world.

Data Production Labour – an investigative discussion at the Institute of Human Obsolescence

On November 10 the Institute of Human Obsolescence (IoHO) founded by artist and activist Manuel Beltrán, organized a discussion in the context of the Data Production Labor series to investigate the hidden dynamics behind our data work. There were three installations on show that visualized data labor in different ways.

IoHO is an artistic research project investigating the repositioning of human labor in a time where manual and intellectual labor are increasingly being performed by machines and new forms of inequality and exploitation arise. With a series of public events the IoHO aims to create an understanding of the production of data as a form of labor. With a new understanding of our relation to work, it might become possible to negotiate the terms of data labor and claim a better position for human workers.

Yes. You and me are data workers. The second we enter the web, go online, we produce data with every little move we make or don’t make. And this data is turned into Big Capital by Big Tech. And, of course you know this already or have at least a vague notion that this is how the internet works, while going about your daily business.

The panel with Manuel Beltrán, Katrin Fritsch, Luis Rodil-Fernández and Ksenia Ermoshina.

The investigation kicked off with a discussion about the narrative of the user. In this narrative, users of free services do not question the technology that they use. They don’t question it because, well, it’s a free service, right? Not having any expectations, users are passive and don’t feel accountable for their (micro) actions. Besides, the services are very convenient. So, from a user’s perspective, why ask questions?

From this starting point the hidden infrastructures behind the seemingly innocent or simple tasks that we perform online were discussed. During this session many topics were brought up that provoked plenty of questions about the human in the loop. In an A.I. based economy digital labor is the currency and this labor is used, among other things, to train algorithms. While a lot of this labor is indeed framed as a form of labor (or Human Intelligence (micro) tasks), much of our digital work is done unknowingly. For instance, when you have to prove that you are not a robot to sign up for a newsletter, and you have to solve one of reCAPTCHA’s traffic light puzzles, you might also be training algorithms for military drones. This seemingly innocent task produced data (value) for Google and was done without consent or the possibility to negotiate what this data is used for.

During the discussion the possibility of a Data Workers Union, that was founded by the IoHO in 2017, was discussed in the context of cultural differences, tradeoffs between privacy and security, political organization of citizens as users of platform governments, and more. What is to be done remains an open question that needs continuous investigation and updating.

Update:

These days you can just check the ‘I’m not a robot’ box and you may proceed without making some puzzle. Or the checkbox does not even show up. By tracking your online behavior and clicking patterns Google already knows that you are not a robot. Besides, users found the security check to be very annoying. With another layer of technology moving into the background, signing up for a newsletter just became a bit more convenient and asking questions a bit harder.

INC herpubliceert De Muur (1984)–Interview met de schrijvers Jan de Graaf & Wim Nijenhuis

Hierbij presenteert het Instituut voor netwerkcultuur met trots de herpublicatie van De Muur (Uitgeverij 010, 1984), geschreven door Donald van Dansik, Jan de Graaf en Wim Nijenhuis met foto’s van Piet Rook van de Berlijnse Muur. Hier vind je de pdf en hier de e-pub. Met dank aan Leonieke van Dipten (Shanghai) voor de productie.

Inleiding door Geert Lovink, November 2018

Ik las De Muur in het ommuurde West-Berlijn zelf, net nadat het boek was uitgekomen, in een kraakpand aan de Potsdammerstrasse waar ik toen woonde. Eind 1981 had ik al eerdere publicaties van deze schrijvers verslonden, namelijk Meten en regelen aan de stad (Jan de Graaf,/Ad Habets/Wim Nijenhuis) en Machinaties (Jan de Graaf/Wim Nijenhuis), beiden met foto’s van Piet Rook.

De Muur verscheen tijdens de kruisraketten crisis, de laatste, hevige stuiptrekkingen van de Koude Oorlog, vlak voor de komst van Gorbatshov. Ten tijde van het Orwelljaar 1984 wees niets op de Val van Muur, 5 jaar later. Of waren er toch onzichtbare tekenen van een komende implosie? Historisch gezien is dit marginale geschrift uit de koker van de Nederlandse architectuurtheorie een interessante avant-gardische aanwijzing dat er reeds fikse scheuren zaten in de (Westerse) kijk op de Berlijnse Muur. De grote sprong voorwaarts die De Muur maakt is de kijk op dit repressieve politieke fenomeen als een amoreel, materieel object.

Bestaat er buiten de pertinent politieke interpretatie ruimte voor een andere kijk op de muur? De Delftse theoretici zien het trekken van grenzen als een vorm van “isolatie met als oogmerk de therapie van de inkeer.” Is de muur een dam? Terwijl vroeger de muur “waarborg was voor de volmaaktheid van de stad, is hij vandaag de inkarnatie van het scheidend kwaad.” De Berlijnse Muur biedt een retrospectief, als vestingswal is het een anachronisme en geen vitale schakel meer in een militaire architectuur die bepaald wordt door raketten en de electronische lichtsnelheid van de communicatie. In Berlijn aanschouwen we de ‘extase van de muur’. Terwijl “het territorium verdwijnt in het tumulteuze verkeer,” verbergt de muur een schat. “De muur is vervat in een tweespalt van angst en begeerte.” De muur onttrekt energie en zijn zwakte is de bres, de opening, het is een membraan, “tegelijkertijd scheiding en verbinding.” De muur als een wraak op de stad als regelmachine van stromen.

Dit soort theorie en schrijfwijze, in het Nederlands, veroorzaakten bij mij toendertijd een ideologische aardsverschuiving. Hoe was dit mogelijk, vroeg ik me af, om zo poetisch, zo anders te schrijven over harde politieke zaken zoals stadsvernieuwing, buurtinpraak en andere voorbeelden van de repressief-pedagogische sociaal-democratische stadspolitiek in de late jaren van de welvaartstaat? In mijn eigen studie politicologie aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam zaten we nog midden in het ideologie en macht debat tussen Gramsci, Althusser en Foucault. In Delft was men al vele rondes verder, zo leek het wel.

Ik nam dit alles in mij op in de turbulente oprichtingstijd van het weekblad bluf!, op het hoogtepunt van de Amsterdamse kraakbeweging, waar ik aktief aan deelnam. Ook wij zagen de CPN en de PvdA als onze direkte tegenstanders, maar dan vanuit de optiek van de radikale (‘nieuwe’) sociale bewegingen. Het wantrouwen tegenover de inspraakmachine en de ‘stadvernieuwing’ was iets dat wij deelden met deze vreemde theorie orakels uit Delft. Wij deden dat alleen vanuit de praktijk van de stedelijke strijd, geinspireerd door Manuel Castells (ha, de link naar netwerken!). Ik las toendertijd ook Han Meyer die in 1980 met anderen De beheerste stad (Uitgeverij Futile) schreef. Ik had trouwens al eerder met Delftse geschriften kennis gemaakt uit dezelfde kring, de ‘Projektraad’ van de afdeling Bouwkunde van TH Delft, zoals de Marxistische polderleer van Rypke Sierksma die met een kritische lezing kwam van Foucault, Deleuze en Guattari. Sierksma kon ik in 1980 nog goed volgen vanuit de optiek van een 20 jarige Amsterdamse kraker met een pragmatisch-radicaal anarchistisch wereldbeeld. Hij schreef bijvoorbeeld in 1982 het boek Polis en politiek, kraakbeweging, autoritaire staat en stadsanalyse (Delftse universitaire pers). Wat de Graaf, Nijenhuis e.a. schreven opende een totaal ander, maar zeker niet minder radicaal wereldbeeld die mij in de richting van BILWET en de autonome media theorie wezen.

Om nader kennis te maken heb ik toen in de loop der jaren een aantal radio interviews met Wim Nijenhuis gemaakt (die ik eind jaren persoonlijk leerde kennen), waarvan een aantal online staan op archive.org (hier een gesprek over het werk van Paul Virilio).

De INC heruitgave van De Muur is een eerbetoon aan deze NL theorie generatie en hopelijk het begin van een INC serie met soortgelijke publicaties uit die tijd. De theorie van toen kan een inspiratie zijn voor het formuleren van een hedendaagse radicale theorie over smart city, urban platforms en ‘city making’ die verder wil gaan dan de op zich terechte kritiek op de gentrificatie. Mij fascineerde het toen al dat eigenzinnige theorie in het Nederlands bestond. De Delftse theorieproductie uit de jaren 70 en 80 is voor mij een belangrijke inspiratiebron geweest, ook voor ons Instituut voor netwerkcultuur. Nederland mag dan geen filosofen hebben, maar in elk geval hadden we architecten die nadachten, schreven en debatteerden. Wij vroegen ons toen al af: is radicale theorie van Nederlandse bodem ueberhaupt wel mogelijk? Wat zijn onze eigen inspiratiebronnen? De Muur toont aan dat een eigenzinnige theorieproductie in deze oer-pragmatische delta wel degelijk mogelijk was. Vandaar deze heruitgave. Om wat meer achtergronden te geven, besloten we een email interview te maken met twee van de schrijvers.

Geert Lovink (Q): Hoe kwam De Muur tot stand? Kunnen jullie iets vertellen over de intellectuele context in 1984 in Delft?

Jan de Graaf & Wim Nijenhuis (A): De Muur is het resultaat van een conceptuele exercitie, gepaard aan systematisch veldwerk in situ. We kunnen dat een kritische afwijking noemen van een gangbare praktijk, die aangedreven werd door een uitgebreidere visie op de professie stedenbouw. Toen we werkten aan De Muur waren we te gast bij de afdeling stedenbouw van de faculteit Bouwkunde van de Technische Universiteit Delft. Daar werd onderzoek van ‘stad en landschap’ gewoonlijk gezien als stedenbouwkundig onderzoek, opgevat als survey before plan, als (sociografisch) voor-onderzoek in dienst van de legitimatie van een ontwerp. Het ontwerp op zijn beurt werd opgevat als voor-afbeelding van de toekomstige situatie van een gegeven gebied. Analyses die oog hadden voor de grote schaal, de lange duur, complexe samenhangen en voor processen die bepalend waren en zijn niet alleen voor het gebied in kwestie maar ook voor de stedenbouwkundige professie zelf, – professie opgevat als kunde en als wetensveld- ontbraken nagenoeg. Wij behoorden in die tijd tot een kleine subcultuur, ontstaan vanuit de studentenprotesten van de 60er jaren, die besloten hebben af te wijken van het reguliere studieprogramma en tijd te reserveren voor theoretische verkenningen buiten het reguliere vakgebied. Daarvoor bezochten we andere universiteiten en zetten we zelfstandige programma’s op voor literatuurstudie.

Opvallend was ook dat de methode van wat je terrestrische verkenningen kan noemen, nauwelijks overdacht werd. Excursies waren er in overvloed. Ietwat gechargeerd, given area’s werden verkend maar meestal leek een (halve) dagmars voldoende om foto’s te maken die al duizendvoudig vaker en beter gemaakt waren. Terug ‘thuis’ werd tijdens de andere daghelft historisch kaartmateriaal bekeken. Daarmee was het ontwerpgebonden vooronderzoek eigenlijk wel afgerond.

In het kader van onze theoretische studies volgden we al enige tijd de publicaties van het Franse CCI (Centre de Creation Industrielle), een afdeling van het Centre Pompidou. Hier werd het tijdschrift Traverses uitgegeven en allerhande thematische publicaties zoals het mooie boekje Les Portes de La Ville, catalogus van de gelijknamige tentoonstelling van het CCI. In de redactie van Traverses zaten toen o.a. Jean Baudrillard en Paul Virilio. Op deze manier werden we geattendeerd op publicaties van Paul Virilio zoals zijn boekje Vitesse et Politique en zijn Bunker Archeologie. De belangrijkste werken van het CCI, en van Baudrillard en Virilio werden in Duitsland op de voet gevolgd door uitgeverijen als het Merwe Verlag en de tijdschriften Tumult en Freibeuter. In deze werken werd expliciet aandacht besteed aan de relatie tussen stad en techniek, waarbij techniek ook militaire techniek en mediatechniek behelsde. Er werden civiele objecten besproken zoals havens, vliegvelden, kanalen, stadsmuren, autosnelwegen, riolering, en natuurlijk bunkers. (deze lijst is niet uitputtend).

Dit discours bood ons een andere kijk op de stad dan we gewend waren van de TU te Delft en de Nederlandse vakbladen. Deze focusseerden grof gezegd op de projecten van afzonderlijke architecten en hoe deze vanuit hun specifieke theoretische achtergronden omgingen met de stedelijke realiteit. Aan de TU domineerde een ontwerpcultuur die ongebroken schatplichtig was aan de traditie van het modernisme, af en toe afgewisseld door het postmodernisme, dit alles in toenemende mate overkoepeld door een Rem Koolhaas in opkomst. Als we vragen naar de architectuurtheorie van die tijd dan moeten we wijzen op het neoavantgardistische en humanistische denken van Herzberger en Van Eyck, die pleitten voor een redding van de stad en de stedelijke gemeenschap door middel van verleidelijke utopische architectuur (voorafbeeldingen, symbolen van het mogelijke). Daarnaast was er het marxistisch denken, waarbij de volgelingen van Althusser zich bezighielden met ideologiekritiek en alternatieve methoden voor stedenbouw en die van Manfredo Tafuri met allerlei varianten van historische kritiek. Voor verdere toelichting op de achtergrond verwijzen we naar het artikel ‘The Image of the City and the Process of Planning’ in Wim Nijenhuis’ The Riddle of the Real City (p.195) dat als e-pub door het Instituut voor Netwerkcultuur is uitgegeven.

Onze ‘brede’ en kritische vakopvatting werd in die tijd gevoed door een reeks snelle theoretische transformaties die zich voltrokken binnen een relatief kleine subcultuur van studenten en medewerkers uit de zg. Projectraad (een op maatschappijkritiek gericht werkverband dat was voortgekomen uit de studentenrevolte van de jaren 60) en groepen studenten en medewerkers rond de colleges kunstgeschiedenis van Kees Vollemans. De transformaties verliepen van al dan niet (neo)marxistische sociologie, naar de architectuurgeschiedenis van Tafuri, en vervolgens de theorieën van Foucault, Deleuze en Baudrillard. Deze transformaties betekenden ook een voortgaande correctie van en kritiek op de rol van de al dan niet Marxistische sociologie bij de verklaringsmodellen voor de productie van architectuur en stedenbouw.

Voorafgaand aan De Muur hadden we al ons afstudeerwerk gepubliceerd (Meten en Regelen aan de Stad), dat handelde over de sociaaldemocratische en humanistische stadsvernieuwing in Rotterdam. Hier hadden we de gangbare sociografische analyse vervangen door elementen van Franse hebben we inzichten van Michel Foucault uitgeprobeerd. In onze studie ‘De Kop van Zuid’, over de relatie tussen havenaanleg en stedenbouw in de 19e eeuw trad het denken van Michel Foucault en aan hem verwante Franse historici expliciet op de voorgrond. Omdat we ruim aandacht besteedden aan grote technische en infrastructurele werken in de 19e eeuw, werd onze aandacht wederom gevestigd op het werk van Paul Virilio. Inhoudelijk leerden we van hem de mogelijkheid om conceptuele exercities los te laten op een concreet object, in dit geval De Muur.

Q: Er spreekt een zekere fascinatie uit jullie tekst voor de Berlijnse muur als architectonisch monument. Is dat niet wrang voor de mensen aan de andere kant van de Muur? Jullie optiek was een Westerse. Zit hier een element in van bewondering voor de wraak van het object? Of een impliciete sympathie voor communisten a la Ulbricht en Honnecker?

A: We hadden ons monumentbegrip al uitgebreid onder invloed van de publicaties van het CCI (Les Portes de La Ville, Traverses), het werk van Virilio (vliegvelden, bunkers, autosnelwegen) en vanwege ons eigen onderzoek naar de Rotterdamse havens in De Kop van Zuid.

Monument betekent normaliter een standbeeld in een park, of op een plein. Vaak is het ook een markant oud gebouw. Het woord monument is in de stedenbouw verbonden met de Monumentenzorg, een praktijk die stamt uit de 19e eeuw. In lijn met deze traditie hebben we het woord ‘monument’ opgevat als ‘het gedenkwaardige’ en de bouw van stedelijke monumenten als het oprichten van symbolen van het gedenkwaardige. Van Nietzsche hadden we geleerd dat monumenten behoren tot de mnemotechniek, de techniek om herinneringen te produceren. Van Nietzsche is ook de uitspraak dat de beste mnemotechnieken altijd gepaard zijn gegaan met een of andere vorm van pijn en offer. Zo geredeneerd was en is het logisch om de muur van Berlijn op te vatten als een exemplaar van buitengewoon geslaagde mnemotechniek.

Of we gefascineerd waren door de muur staat nog te bezien, omdat fascinatie toch meestal zoiets betekent als geboeid zijn, of betoverd zijn door iets. In het begrip klinkt mee dat de bewondering kritiekloos en ongereflecteerd is. Ons idee was echter om de muur eens goed te gaan bekijken en er een stukje gedegen stedenbouwkundig veldwerk aan te besteden. Het idee om de muur eens goed te gaan bekijken als stedenbouwkundig bouwwerk, ic monument, impliceerde juist dat iedere fascinatie gebroken zou worden door de nuchtere en vakmatige inspectie. Zoals eerder gezegd, ons project was in de eerste plaats een ingenieursproject gebaseerd op de techniek van de oculaire inspectie ter plekke, om een uitdrukking te gebruiken die populair was bij de eerste civiel ingenieurs in de achttiende eeuw. Met de muur als object hebben we op onze eigen manier civic survey bedreven. Onze uitgebreide terrestrische verkenning (160 kilometer muur!) hadden we voorbereid met uitgebreide studie van kaarten van Berlijn, waarop het traject van de muur minutieus was ingetekend. Uitgeselecteerde plekken hebben we te voet opgezocht en rillend van de kou geïnspecteerd met onze laarzen in de modder. De foto´s in het boek zijn dan ook meer dan artistieke impressies. Ze zijn ook documentatie, d.w.z. fotografisch verslag van dit veldwerk. Op deze manier wordt de werking van de muur als mediabeeld of als publicitair icoon, die vaak wel effecten heeft van fascinatie, doorbroken.

We hebben de muur express van een kant benaderd. Je begrijpt dat een fotografische inspectie van de andere kant in 1984 praktisch onmogelijk was. In ieder geval zijn wij er niet aan begonnen. Dit betekent dat de fotografische standpunten en dus ook de standpunten van de oculaire inspectie ter plekke zich systematisch in het territorium van West-Berlijn hebben bevonden. Een aantal malen zijn we doorgedrongen tot standpunten die zich buiten West-Berlijn bevonden, in de zone van de Muur, die in zijn geheel op het territorium lag van Oost-Berlijn. Daar zijn we door het membraam heen gestoten, zonder echter aan te komen aan de andere kant, een ware transgressie in de zin van Foucault.

Vandaag de dag blijkt dat de monumentwerking van de muur ook persisteert na zijn afbraak en dat dit geldt voor mensen van Oost-en West. Maar dan praten we wel over de muur als restant, zoals bij de Bernauer Strasse, of als replica, zie de recente pogingen om op de Museen Insel een ‘Berlijnse Muur’ te realiseren onder de paraplu van de kunst.

In relatie tot het succes van de muur is de westerse optiek de meest onthutsende. Tenslotte heeft de muur uiteindelijk gefaald voor wat betreft de strategie van de DDR, als dam in de mensenstroom, wat niet gezegd kan worden van de (reactieve) strategieën van de westerse machten. Hoewel ons concrete optiek in het westen lag, hopen we dat onze abstracte, theoretische optiek zich los heeft gemaakt van de tegenstelling tussen oost en west. In die zin hebben we gespeeld met het begrip ´objectieve optiek´ door te stellen dat de muur de ongeluksverschijning was, een fatale turbulentie, die veroorzaakt werd door het geweld van het nucleaire evenwicht en de ‘geloofscontroversen’ die onder deze paraplu werden uitgevochten. Morele of politieke oordelen doen hier niet ter zake en leveren thesen op die van secundair belang zijn.

Of hier sprake is van de ‘wraak van het object’? In zekere zin wel, want de muur was een object, dat in al zijn monstruositeit en al zijn banaliteit ontstond, bestond en ten onder ging buiten de ‘wil van de mens’ om, in ieder geval van de direct betrokkenen. Net zoals de opkomst en de ondergang van de historische vestingmuur gevat was in een keten van onontkomelijke noodzakelijkheden.

Q: De Berlijnse muur viel vijf jaar na de publicatie van jullie boek. Hoe keken jullie tegen deze historische gebeurtenis aan? Is het terecht om te zeggen dat de stenen muur toen werd vervangen door een elektronische in de vorm van Schengen en Frontex? Ruim dertig jaar later zijn de grensmuren in Europa weer terug van nooit weg geweest. De meest bekende is wellicht de Orban muur tussen Hongarije en Servie om vluchtelingen tegen te houden.

A: De muur kon vallen, omdat zijn ‘goddelijke’ garant, de nucleaire afschrikking, aan het wankelen was gebracht door de politiek van economische uitputting van Reagan en de verleiding van de massa’s door de moderne media. We zijn nog niet helemaal af van het nucleaire evenwicht, tegenwoordig is ze niet meer bipolair, maar multipolair. Tegelijkertijd is het duidelijk dat het militaire genius hevig op zoek is naar wegen om te ontsnappen aan de beperkingen die hem worden opgelegd door de atoomparaplu. Binnen dit gegeven belichaamt Schengen het neoliberale ideaal van de transparante wereld van de ongebreidelde mobiliteit, dat vroeger door de nucleaire afschrikking binnen de perken werd gehouden. Frontex belichaamt de onmogelijkheid van deze ideologie in het tijdperk van de historische catastrofe. Het verschil met de Berlijnse Muur is dat Frontex niet op dezelfde manier wordt gedekt door nucleaire afschrikking en bijbehorende pacten. Frontex heeft te maken met bipolaire afschrikking en een wereld die geteisterd wordt door een genadeloze krimp van de aardbol, het kleiner worden van de afstanden en de toenemende interactie tussen alle delen van de wereld onder invloed van de kapitalistische economie en de techniek van de communicatie (overigens ook een militaire uitvinding). Misschien is de migratie waartegen men nu vecht inderdaad een ‘wraak van het object’, of misschien nog eerder: de wraak van de middelen, met name de satellieten die satelliettelevisie, delen van internet en de mobile telefonie mogelijk maken.

Clausewitz parafraserend kunnen we zeggen dat Frontex de voortzetting is van de Muur onder andere omstandigheden en met andere middelen.

Q: De herpublicatie van De Muur kan zeker ook gelezen worden als een eerbetoon aan de onlangs overleden Paul Virilio. Hoe zien jullie de status van zijn werk op dit moment?

Ons boek kent zeker raakvlakken met het werk van Virilio, maar mag niet gezien worden als een pure toepassing van zijn filosofie.

Om de status van het werk van Virilio vandaag de dag te kunnen bespreken moeten we een aantal facetten onderscheiden in zijn werk, te weten zijn schriftuur, zijn filosofie, zijn onderwerpen en zijn concepten/thesen.

Zijn schriftuur was destijds opvallend origineel. Hij werkte met textuele montage, d.w.z. het naast elkaar zetten van strijdige, of spannende concepten. Hij gebruikte daarvoor uitspraken uit allerlei bereiken. Hij hield van het treffende citaat, dat vaak in hoofdletters en in bold werd afgedrukt. De montage maakte het mogelijk uiteenlopende wetenschappelijke domeinen en kunstvormen als literatuur, film en dichtkunst met elkaar te verknopen. De relatie van zijn schriftuur met de filmmontage en reclametechniek was opvallend. Net als televisiereclame waren zijn teksten zelden direct, maar eerder toespelend van aard. In interviews legde hij uit, dat voor een goed effect niet alles meer uitvoerig uitgelegd hoefde te worden en dat we ons kunnen beperken tot een geconcentreerde en soms onvolledige vertelling.

Zijn filosofie was tweeledig. Hij geloofde in de kracht van het woord en de strijd van de ideeën, maar hij geloofde niet in de noodzaak van het wetenschappelijke begrip. Daarnaast ging hij uit van de stelling dat onze geschiedenis een fatale kromming heeft ondergaan en dat de tijd van de vooruitgang getransmuteerd is in de tijd van de catastrofe. Volgens Virilio komt het er nu op aan om alle technische uitvindingen te checken op hun negatieve en onbedoelde effecten. Zijn alles overkoepelende premisse is hier, dat iedere technologische innovatie zijn eigen specifieke vorm van ongeval in zich draagt. Binnen dit gegeven was zijn methode de transhistorische apocalyptiek, dat wil zeggen: de lezer opwekken tot waakzaamheid en wantrouwen tegenover actuele tendensen door middels geniale schakelingen met gebeurtenissen uit het verleden te voorspellen welke ongevallen nieuwe uitvindingen zullen gaan veroorzaken en welke negatieve bijwerkingen ze zullen hebben.

Zijn voorspellingen betroffen vaak de stad en de maatschappij in relatie tot technologische/militaire innovatie. Wat is de invloed van het verkeer op de stad, wat is de invloed van de film en later de telecommunicatie op individu en maatschappij en gemeenschap? Wat is de rol van het militaire intellect binnen dergelijke technologische ontwikkelingen en hoe reageren maatschappijen op catastrofes?

Uit deze vragen zijn talloze hypothesen en concepten voortgekomen zoals dromologie, dromocratie, ontsnappingssnelheid, monument van het moment e.d.

Virilio heeft in de jaren 90 veel succes gehad, hier en in de Verenigde Staten. Zijn werk is structureel opgepakt in Duitsland (Peter Weibel e.a.) en Engeland (John Armetage), beiden werkzaam in de wereld van de kunsten. In Nederland werd Virilio bestudeerd in een kleine kring. Dat hij in de academische wereld niet aansloeg is niet verwonderlijk voor een denker die het ´begrip´ afwijst. Op onze techniekfaculteiten stuitte zijn apocalyptische negativiteit op weerstand, mede omdat de ingenieurswetenschappen nu eenmaal de incorporatie zijn van de hoop. Onze Denker des Vaderlands, Hans Achterhuis, destijds professor voor filosofie van de techniek in Twente, lanceerde begin deze eeuw zelfs een heuse actie tegen Virilio’s zogenaamde ‘dystopische’ schrijven, aangespoord door zijn eigen verlangen naar utopie. De meeste architecten negeerden Virilio, omdat hij geen toepasbare theorie zou hebben opgeleverd. Gezien het bovenstaande is er veel voor te zeggen dat Virilio in Nederland in ieder geval een echte ‘underground’ denker was en is gebleven. En dat lijkt ons ook goed zo, want hoe meer zijn werk aan de oppervlakte komt en opgenomen wordt in institutionele verbanden, hoe minder de werkzaamheid ervan wordt.

Merkwaardig genoeg is zijn apocalyptische methode tegenwoordig teruggekeerd alsof ze nooit is weggeweest, ondanks, of dankzij 30 jaar postmodernistische weerstand. Denk aan Sloterdijk, ‘Je moet je leven veranderen’, of Bruno Latour met ‘Oog in Oog met Gaia’. In deze werken wordt Virilio (terecht) niet geciteerd, maar hun apocalyptische toon is niet te overzien. Het boek ‘Homo Sapiens’ van Yuval Harari, dat de hele wereld lijkt te bestormen, is niets anders dan een staaltje van hoogstaande apocalyptiek. Van iedere pagina druipt het verlangen om ons wakker te schudden en ons wantrouwen te wekken tegen actuele tendensen, al is de ironiserende stijl van Virilio hier vervangen door de ietwat drammerige stijl van de intellectuele chantage.

Hoewel Virilio’s concepten, we noemen ze nog maar eens een keer, zoals snelheid als Ueber-Ich, dromologie, dromocratie, monument van het moment, heldere en indirecte waarneming, schrijven tegen het scherm ed. niet zijn ingeburgerd, staan zijn hypothesen overeind als een rots. En altijd scheiden ze de wereld van de ingenieurs van die van de cultuur.

In de jaren negentig hebben we op diverse scholen les gegeven in Virilio. Kortgeleden belde een student ons op: ‘Hoe is het om mee te maken dat er in de maatschappij gebeurt wat u destijds aan de hand van Virilio heeft voorspeld?’

n Machinaties gelezen, van dezelfde auteurs. Deze leeservaring van Delftse architektuurtheorie was toen een heftige en verwarrende ervaring geweest.

Geert Lovink (Q): Hoe kwam De Muur tot stand? Kunnen jullie iets vertellen over de intellectuele context in 1984 in Delft?

Jan de Graaf & Wim Nijenhuis (A): De Muur is het resultaat van een conceptuele exercitie, gepaard aan systematisch veldwerk in situ. We kunnen dat een kritische afwijking noemen van een gangbare praktijk, die aangedreven werd door een uitgebreidere visie op de professie stedenbouw. Toen we werkten aan De Muur waren we te gast bij de afdeling stedenbouw van de faculteit Bouwkunde van de Technische Universiteit Delft. Daar werd onderzoek van ‘stad en landschap’ gewoonlijk gezien als stedenbouwkundig onderzoek, opgevat als survey before plan, als (sociografisch) voor-onderzoek in dienst van de legitimatie van een ontwerp. Het ontwerp op zijn beurt werd opgevat als voor-afbeelding van de toekomstige situatie van een gegeven gebied. Analyses die oog hadden voor de grote schaal, de lange duur, complexe samenhangen en voor processen die bepalend waren en zijn niet alleen voor het gebied in kwestie maar ook voor de stedenbouwkundige professie zelf, – professie opgevat als kunde en als wetensveld- ontbraken nagenoeg. Wij behoorden in die tijd tot een kleine subcultuur, ontstaan vanuit de studentenprotesten van de 60er jaren, die besloten hebben af te wijken van het reguliere studieprogramma en tijd te reserveren voor theoretische verkenningen buiten het reguliere vakgebied. Daarvoor bezochten we andere universiteiten en zetten we zelfstandige programma’s op voor literatuurstudie.

Opvallend was ook dat de methode van wat je terrestrische verkenningen kan noemen, nauwelijks overdacht werd. Excursies waren er in overvloed. Ietwat gechargeerd, given area’s werden verkend maar meestal leek een (halve) dagmars voldoende om foto’s te maken die al duizendvoudig vaker en beter gemaakt waren. Terug ‘thuis’ werd tijdens de andere daghelft historisch kaartmateriaal bekeken. Daarmee was het ontwerpgebonden vooronderzoek eigenlijk wel afgerond.

In het kader van onze theoretische studies volgden we al enige tijd de publicaties van het Franse CCI (Centre de Creation Industrielle), een afdeling van het Centre Pompidou. Hier werd het tijdschrift Traverses uitgegeven en allerhande thematische publicaties zoals het mooie boekje Les Portes de La Ville, catalogus van de gelijknamige tentoonstelling van het CCI. In de redactie van Traverses zaten toen o.a. Jean Baudrillard en Paul Virilio. Op deze manier werden we geattendeerd op publicaties van Paul Virilio zoals zijn boekje Vitesse et Politique en zijn Bunker Archeologie. De belangrijkste werken van het CCI, en van Baudrillard en Virilio werden in Duitsland op de voet gevolgd door uitgeverijen als het Merwe Verlag en de tijdschriften Tumult en Freibeuter. In deze werken werd expliciet aandacht besteed aan de relatie tussen stad en techniek, waarbij techniek ook militaire techniek en mediatechniek behelsde. Er werden civiele objecten besproken zoals havens, vliegvelden, kanalen, stadsmuren, autosnelwegen, riolering, en natuurlijk bunkers. (deze lijst is niet uitputtend).

Dit discours bood ons een andere kijk op de stad dan we gewend waren van de TU te Delft en de Nederlandse vakbladen. Deze focusseerden grof gezegd op de projecten van afzonderlijke architecten en hoe deze vanuit hun specifieke theoretische achtergronden omgingen met de stedelijke realiteit. Aan de TU domineerde een ontwerpcultuur die ongebroken schatplichtig was aan de traditie van het modernisme, af en toe afgewisseld door het postmodernisme, dit alles in toenemende mate overkoepeld door een Rem Koolhaas in opkomst. Als we vragen naar de architectuurtheorie van die tijd dan moeten we wijzen op het neonavant-gardistische en humanistische denken van Herzberger en Van Eyck, die pleitten voor een redding van de stad en de stedelijke gemeenschap door middel van verleidelijke utopische architectuur (voorafbeeldingen, symbolen van het mogelijke). Daarnaast was er het marxistisch denken, waarbij de volgelingen van Althusser zich bezighielden met ideologiekritiek en alternatieve methoden voor stedenbouw en die van Manfredo Tafuri met allerlei varianten van historische kritiek. Voor verdere toelichting op de achtergrond verwijzen we naar het artikel ‘The Image of the City and the Process of Planning’ in Wim Nijenhuis’ The Riddle of the Real City (p.195) dat als e-pub door het Instituut voor Netwerkcultuur is uitgegeven.

Onze ‘brede’ en kritische vakopvatting werd in die tijd gevoed door een reeks snelle theoretische transformaties die zich voltrokken binnen een relatief kleine subcultuur van studenten en medewerkers uit de zg. Projectraad (een op maatschappijkritiek gericht werkverband dat was voortgekomen uit de studentenrevolte van de jaren 60) en groepen studenten en medewerkers rond de colleges kunstgeschiedenis van Kees Vollemans. De transformaties verliepen van al dan niet (neo)marxistische sociologie, naar de architectuurgeschiedenis van Tafuri, en vervolgens de theorieën van Foucault, Deleuze en Baudrillard. Deze transformaties betekenden ook een voortgaande correctie van en kritiek op de rol van de al dan niet Marxistische sociologie bij de verklaringsmodellen voor de productie van architectuur en stedenbouw.

Voorafgaand aan De Muur hadden we al ons afstudeerwerk gepubliceerd (Meten en Regelen aan de Stad), dat handelde over de sociaaldemocratische en humanistische stadsvernieuwing in Rotterdam. Hier hadden we de gangbare sociografische analyse vervangen door elementen van Franse hebben we inzichten van Michel Foucault uitgeprobeerd. In onze studie ‘De Kop van Zuid’, over de relatie tussen havenaanleg en stedenbouw in de 19e eeuw trad het denken van Michel Foucault en aan hem verwante Franse historici expliciet op de voorgrond. Omdat we ruim aandacht besteedden aan grote technische en infrastructurele werken in de 19e eeuw, werd onze aandacht wederom gevestigd op het werk van Paul Virilio. Inhoudelijk leerden we van hem de mogelijkheid om conceptuele exercities los te laten op een concreet object, in dit geval De Muur.

Q: Er spreekt een zekere fascinatie uit jullie tekst voor de Berlijnse muur als architectonisch monument. Is dat niet wrang voor de mensen aan de andere kant van de Muur? Jullie optiek was een Westerse. Zit hier een element in van bewondering voor de wraak van het object? Of een impliciete sympathie voor communisten a la Ulbricht en Honnecker?

A: We hadden ons monumentbegrip al uitgebreid onder invloed van de publicaties van het CCI (Les Portes de La Ville, Traverses), het werk van Virilio (vliegvelden, bunkers, autosnelwegen) en vanwege ons eigen onderzoek naar de Rotterdamse havens in De Kop van Zuid.

Monument betekent normaliter een standbeeld in een park, of op een plein. Vaak is het ook een markant oud gebouw. Het woord monument is in de stedenbouw verbonden met de Monumentenzorg, een praktijk die stamt uit de 19e eeuw. In lijn met deze traditie hebben we het woord ‘monument’ opgevat als ‘het gedenkwaardige’ en de bouw van stedelijke monumenten als het oprichten van symbolen van het gedenkwaardige. Van Nietzsche hadden we geleerd dat monumenten behoren tot de mnemotechniek, de techniek om herinneringen te produceren. Van Nietzsche is ook de uitspraak dat de beste mnemotechnieken altijd gepaard zijn gegaan met een of andere vorm van pijn en offer. Zo geredeneerd was en is het logisch om de muur van Berlijn op te vatten als een exemplaar van buitengewoon geslaagde mnemotechniek.

Of we gefascineerd waren door de muur staat nog te bezien, omdat fascinatie toch meestal zoiets betekent als geboeid zijn, of betoverd zijn door iets. In het begrip klinkt mee dat de bewondering kritiekloos en ongereflecteerd is. Ons idee was echter om de muur eens goed te gaan bekijken en er een stukje gedegen stedenbouwkundig veldwerk aan te besteden. Het idee om de muur eens goed te gaan bekijken als stedenbouwkundig bouwwerk, ic monument, impliceerde juist dat iedere fascinatie gebroken zou worden door de nuchtere en vakmatige inspectie. Zoals eerder gezegd, ons project was in de eerste plaats een ingenieursproject gebaseerd op de techniek van de oculaire inspectie ter plekke, om een uitdrukking te gebruiken die populair was bij de eerste civiel ingenieurs in de achttiende eeuw. Met de muur als object hebben we op onze eigen manier civic survey bedreven. Onze uitgebreide terrestrische verkenning (160 kilometer muur!) hadden we voorbereid met uitgebreide studie van kaarten van Berlijn, waarop het traject van de muur minutieus was ingetekend. Uitgeselecteerde plekken hebben we te voet opgezocht en rillend van de kou geïnspecteerd met onze laarzen in de modder. De foto´s in het boek zijn dan ook meer dan artistieke impressies. Ze zijn ook documentatie, d.w.z. fotografisch verslag van dit veldwerk. Op deze manier wordt de werking van de muur als mediabeeld of als publicitair icoon, die vaak wel effecten heeft van fascinatie, doorbroken.

We hebben de muur express van een kant benaderd. Je begrijpt dat een fotografische inspectie van de andere kant in 1984 praktisch onmogelijk was. In ieder geval zijn wij er niet aan begonnen. Dit betekent dat de fotografische standpunten en dus ook de standpunten van de oculaire inspectie ter plekke zich systematisch in het territorium van West-Berlijn hebben bevonden. Een aantal malen zijn we doorgedrongen tot standpunten die zich buiten West-Berlijn bevonden, in de zone van de Muur, die in zijn geheel op het territorium lag van Oost-Berlijn. Daar zijn we door het membraam heen gestoten, zonder echter aan te komen aan de andere kant, een ware transgressie in de zin van Foucault.

Vandaag de dag blijkt dat de monumentwerking van de muur ook persisteert na zijn afbraak en dat dit geldt voor mensen van Oost-en West. Maar dan praten we wel over de muur als restant, zoals bij de Bernauer Strasse, of als replica, zie de recente pogingen om op de Museen Insel een ‘Berlijnse Muur’ te realiseren onder de paraplu van de kunst.

In relatie tot het succes van de muur is de westerse optiek de meest onthutsende. Tenslotte heeft de muur uiteindelijk gefaald voor wat betreft de strategie van de DDR, als dam in de mensenstroom, wat niet gezegd kan worden van de (reactieve) strategieën van de westerse machten. Hoewel ons concrete optiek in het westen lag, hopen we dat onze abstracte, theoretische optiek zich los heeft gemaakt van de tegenstelling tussen oost en west. In die zin hebben we gespeeld met het begrip ´objectieve optiek´ door te stellen dat de muur de ongeluksverschijning was, een fatale turbulentie, die veroorzaakt werd door het geweld van het nucleaire evenwicht en de ‘geloofscontroversen’ die onder deze paraplu werden uitgevochten. Morele of politieke oordelen doen hier niet ter zake en leveren thesen op die van secundair belang zijn.

Of hier sprake is van de ‘wraak van het object’? In zekere zin wel, want de muur was een object, dat in al zijn monstruositeit en al zijn banaliteit ontstond, bestond en ten onder ging buiten de ‘wil van de mens’ om, in ieder geval van de direct betrokkenen. Net zoals de opkomst en de ondergang van de historische vestingmuur gevat was in een keten van onontkomelijke noodzakelijkheden.

Q: De Berlijnse muur viel vijf jaar na de publicatie van jullie boek. Hoe keken jullie tegen deze historische gebeurtenis aan? Is het terecht om te zeggen dat de stenen muur toen werd vervangen door een elektronische in de vorm van Schengen en Frontex? Ruim dertig jaar later zijn de grensmuren in Europa weer terug van nooit weg geweest. De meest bekende is wellicht de Orban muur tussen Hongarije en Servie om vluchtelingen tegen te houden.

A: De muur kon vallen, omdat zijn ‘goddelijke’ garant, de nucleaire afschrikking, aan het wankelen was gebracht door de politiek van economische uitputting van Reagan en de verleiding van de massa’s door de moderne media. We zijn nog niet helemaal af van het nucleaire evenwicht, tegenwoordig is ze niet meer bipolair, maar multipolair. Tegelijkertijd is het duidelijk dat het militaire genius hevig op zoek is naar wegen om te ontsnappen aan de beperkingen die hem worden opgelegd door de atoomparaplu. Binnen dit gegeven belichaamt Schengen het neoliberale ideaal van de transparante wereld van de ongebreidelde mobiliteit, dat vroeger door de nucleaire afschrikking binnen de perken werd gehouden. Frontex belichaamt de onmogelijkheid van deze ideologie in het tijdperk van de historische catastrofe. Het verschil met de Berlijnse Muur is dat Frontex niet op dezelfde manier wordt gedekt door nucleaire afschrikking en bijbehorende pacten. Frontex heeft te maken met bipolaire afschrikking en een wereld die geteisterd wordt door een genadeloze krimp van de aardbol, het kleiner worden van de afstanden en de toenemende interactie tussen alle delen van de wereld onder invloed van de kapitalistische economie en de techniek van de communicatie (overigens ook een militaire uitvinding). Misschien is de migratie waartegen men nu vecht inderdaad een ‘wraak van het object’, of misschien nog eerder: de wraak van de middelen, met name de satellieten die satelliettelevisie, delen van internet en de mobile telefonie mogelijk maken.

Clausewitz parafraserend kunnen we zeggen dat Frontex de voortzetting is van de Muur onder andere omstandigheden en met andere middelen.

Q: De herpublicatie van De Muur kan zeker ook gelezen worden als een eerbetoon aan de onlangs overleden Paul Virilio. Hoe zien jullie de status van zijn werk op dit moment?

Ons boek kent zeker raakvlakken met het werk van Virilio, maar mag niet gezien worden als een pure toepassing van zijn filosofie.

Om de status van het werk van Virilio vandaag de dag te kunnen bespreken moeten we een aantal facetten onderscheiden in zijn werk, te weten zijn schriftuur, zijn filosofie, zijn onderwerpen en zijn concepten/thesen.

Zijn schriftuur was destijds opvallend origineel. Hij werkte met textuele montage, d.w.z. het naast elkaar zetten van strijdige, of spannende concepten. Hij gebruikte daarvoor uitspraken uit allerlei bereiken. Hij hield van het treffende citaat, dat vaak in hoofdletters en in bold werd afgedrukt. De montage maakte het mogelijk uiteenlopende wetenschappelijke domeinen en kunstvormen als literatuur, film en dichtkunst met elkaar te verknopen. De relatie van zijn schriftuur met de filmmontage en reclametechniek was opvallend. Net als televisiereclame waren zijn teksten zelden direct, maar eerder toespelend van aard. In interviews legde hij uit, dat voor een goed effect niet alles meer uitvoerig uitgelegd hoefde te worden en dat we ons kunnen beperken tot een geconcentreerde en soms onvolledige vertelling.

Zijn filosofie was tweeledig. Hij geloofde in de kracht van het woord en de strijd van de ideeën, maar hij geloofde niet in de noodzaak van het wetenschappelijke begrip. Daarnaast ging hij uit van de stelling dat onze geschiedenis een fatale kromming heeft ondergaan en dat de tijd van de vooruitgang getransmuteerd is in de tijd van de catastrofe. Volgens Virilio komt het er nu op aan om alle technische uitvindingen te checken op hun negatieve en onbedoelde effecten. Zijn alles overkoepelende premisse is hier, dat iedere technologische innovatie zijn eigen specifieke vorm van ongeval in zich draagt. Binnen dit gegeven was zijn methode de transhistorische apocalyptiek, dat wil zeggen: de lezer opwekken tot waakzaamheid en wantrouwen tegenover actuele tendensen door middels geniale schakelingen met gebeurtenissen uit het verleden te voorspellen welke ongevallen nieuwe uitvindingen zullen gaan veroorzaken en welke negatieve bijwerkingen ze zullen hebben.

Zijn voorspellingen betroffen vaak de stad en de maatschappij in relatie tot technologische/militaire innovatie. Wat is de invloed van het verkeer op de stad, wat is de invloed van de film en later de telecommunicatie op individu en maatschappij en gemeenschap? Wat is de rol van het militaire intellect binnen dergelijke technologische ontwikkelingen en hoe reageren maatschappijen op catastrofes?

Uit deze vragen zijn talloze hypothesen en concepten voortgekomen zoals dromologie, dromocratie, ontsnappingssnelheid, monument van het moment e.d.

Virilio heeft in de jaren 90 veel succes gehad, hier en in de Verenigde Staten. Zijn werk is structureel opgepakt in Duitsland (Peter Weibel e.a.) en Engeland (John Armitage), beiden werkzaam in de wereld van de kunsten. In Nederland werd Virilio bestudeerd in een kleine kring. Dat hij in de academische wereld niet aansloeg is niet verwonderlijk voor een denker die het ´begrip´ afwijst. Op onze techniekfaculteiten stuitte zijn apocalyptische negativiteit op weerstand, mede omdat de ingenieurswetenschappen nu eenmaal de incorporatie zijn van de hoop. Onze Denker des Vaderlands, Hans Achterhuis, destijds professor voor filosofie van de techniek in Twente, lanceerde begin deze eeuw zelfs een heuse actie tegen Virilio’s zogenaamde ‘dystopische’ schrijven, aangespoord door zijn eigen verlangen naar utopie. De meeste architecten negeerden Virilio, omdat hij geen toepasbare theorie zou hebben opgeleverd. Gezien het bovenstaande is er veel voor te zeggen dat Virilio in Nederland in ieder geval een echte ‘underground’ denker was en is gebleven. En dat lijkt ons ook goed zo, want hoe meer zijn werk aan de oppervlakte komt en opgenomen wordt in institutionele verbanden, hoe minder de werkzaamheid ervan wordt.

Merkwaardig genoeg is zijn apocalyptische methode tegenwoordig teruggekeerd alsof ze nooit is weggeweest, ondanks, of dankzij 30 jaar postmodernistische weerstand. Denk aan Sloterdijk, ‘Je moet je leven veranderen’, of Bruno Latour met ‘Oog in Oog met Gaia’. In deze werken wordt Virilio (terecht) niet geciteerd, maar hun apocalyptische toon is niet te overzien. Het boek ‘Homo Sapiens’ van Yuval Harari, dat de hele wereld lijkt te bestormen, is niets anders dan een staaltje van hoogstaande apocalyptiek. Van iedere pagina druipt het verlangen om ons wakker te schudden en ons wantrouwen te wekken tegen actuele tendensen, al is de ironiserende stijl van Virilio hier vervangen door de ietwat drammerige stijl van de intellectuele chantage.

Hoewel Virilio’s concepten, we noemen ze nog maar eens een keer, zoals snelheid als Ueber-Ich, dromologie, dromocratie, monument van het moment, heldere en indirecte waarneming, schrijven tegen het scherm ed. niet zijn ingeburgerd, staan zijn hypothesen overeind als een rots. En altijd scheiden ze de wereld van de ingenieurs van die van de cultuur.

In de jaren negentig hebben we op diverse scholen les gegeven in Virilio. Kortgeleden belde een student ons op: ‘Hoe is het om mee te maken dat er in de maatschappij gebeurt wat u destijds aan de hand van Virilio heeft voorspeld?’

Mr. and Mrs. Talking Machine: The Euphonia, the Phonograph, and the Gendering of Nineteenth Century Mechanical Speech

In the early 1870s a talking machine, contrived by the aptly-named Joseph Faber appeared before audiences in the United States. Dubbed the “talking head” by its inventor, it did not merely record the spoken word and then reproduce it, but actually synthesized speech mechanically. It featured a fantastically complex pneumatic system in which air was pushed by a bellows through a replica of the human speech apparatus, which included a mouth cavity, tongue, palate, jaw and cheeks. To control the machine’s articulation, all of these components were hooked up to a keyboard with seventeen keys— sixteen for various phonemes and one to control the Euphonia’s artificial glottis. Interestingly, the machine’s handler had taken one more step in readying it for the stage, affixing to its front a mannequin. Its audiences in the 1870s found themselves in front of a machine disguised to look like a white European woman.

Unidentified image of Joseph Faber’s Euphonia, public domain. c. 1870

By the end of the decade, however, audiences in the United States and beyond crowded into auditoriums, churches and clubhouses to hear another kind of “talking machine” altogether. In late 1877 Thomas Edison announced his invention of the phonograph, a device capable of capturing the spoken words of subjects and then reproducing them at a later time. The next year the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company sent dozens of exhibitors out from their headquarters in New York to edify and amuse audiences with the new invention. Like Faber before them, the company and its exhibitors anthropomorphized their talking machines, and, while never giving their phonographs hair, clothing or faces, they did forge a remarkably concrete and unanimous understanding of “who” the phonograph was. It was “Mr. Phonograph.”

Why had the Euphonia become female and the phonograph male? In this post, I peel apart some of the entanglements of gender and speech that operated in the Faber Euphonia and the phonograph, paying particular attention to the technological and material circumstances of those entanglements. What I argue is that the materiality of these technologies must itself be taken into account in deciphering the gendered logics brought to bear on the problem of mechanical speech. Put another way, when Faber and Edison mechanically configured their talking machines, they also engineered their uses and their apparent relationships with users. By prescribing the types of relationships the machine would enact with users, they constructed its “ideal” gender in ways that also drew on and reinforced existing assumptions about race and class.

Of course, users could and did adapt talking machines to their own ends. They tinkered with its construction or simply disregarded manufacturers’ prescriptions. The physical design of talking machines as well as the weight of social-sanction threw up non-negligible obstacles to subversive tinkerers and imaginers.

Born in Freiburg, Germany around 1800, Joseph Faber worked as an astronomer at the Vienna Observatory until an infection damaged his eyesight. Forced to find other work, he settled on the unlikely occupation of “tinkerer” and sometime in the 1820s began his quest for perfected mechanical speech. The work was long and arduous, but by no later than 1843 Faber was exhibiting his talking machine on the continent. In 1844 he left Europe to exhibit it in the United States, but in 1846 headed back across the Atlantic for a run at London’s Egyptian Hall.

That Faber conceived of his invention in gendered terms from the outset is reflected in his name for it—“Euphonia”—a designation meaning “pleasant sounding” and whose Latin suffix conspicuously signals a female identity. Interestingly, however, the inventor had not originally designed the machine to look like a woman but, rather, as an exoticized male “Turk.”

“The Euphonia,” August 8, 1846, Illustrated London News, 96.

A writer for Chambers Edinburgh Journal characterized the mannequin’s original appearance in September of 1846:

The half figure of a man, the size known to artists as kit kat, dressed in Turkish costume, is seen resting, upon the side of a table, surrounded by crimson drapery, with its arms crossed upon its bosom. The body of the figure is dressed in blue merino, its head is surmounted by a Turkish cap, and the lower part of the face is covered with a dense flowing beard, which hangs down so as to conceal some portion of the mechanism contained in the throat.

What to make of Faber’s decision to present his machine as a “Turk?” One answer, though an unsatisfying one is “convention.” One of the most famous automata in history had been the chess-playing Turk constructed by Wolfgang von Kempelen in the eighteenth century. A close student of von Kempelen’s work on talking machines, Faber would almost certainly have been aware of the precedent. In presenting their machines as “Turks,” however, both Faber and Von Kempelen likely sought to harness particular racialized tropes to generate public interest in their machines. Mystery. Magic. Exoticism. Europeans had long attributed these qualities to the lands and peoples of the Near East and it so happened that these racist representations were also highly appealing qualities in a staged spectacle—particularly ones that purported to push the boundaries of science and engineering.