Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

It has been an abundant decade-plus (!!!) since Alexander Weheliye’s Phonographies “link[ed] the formal structure of W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk to the contemporary mixing practices of DJs” (13) and we want to know how folks have thought about and listened with Du Bois in their work in the intervening years. How does Du Bois as DJ remix both the historiography and the contemporary praxis of sound studies? How does attention to Du Bois’s theories of race and sound encourage us to challenge the ways in which white supremacy has historically shaped American institutions, sensory orientations, and fields of study? What new futures emerge when we listen to Du Bois as a thinker and agent of sound?

Over the next two months, we will be sharing work that reimagines sound studies with Du Bois at the center. Pieces by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, Kristin Moriah, Aaron Carter, Austin Richey, Jennifer Cook, Vanessa Valdés, and Julie Beth Napolin move us toward an decolonized understanding and history of sound studies, showing us how has Du Bois been urging us to attune ourselves to it.

Readers, today’s post by Phillip Luke Sinitere offers a wonderful introduction to W.E.B. Du Bois’s life’s work if he is new to you, and a finely-wrought analysis of what the sound of Du Bois’s voice–through first hand accounts and recordings–offers folks already well-acquainted.

–Jennifer Lynn Stoever and Liana Silva, Eds.

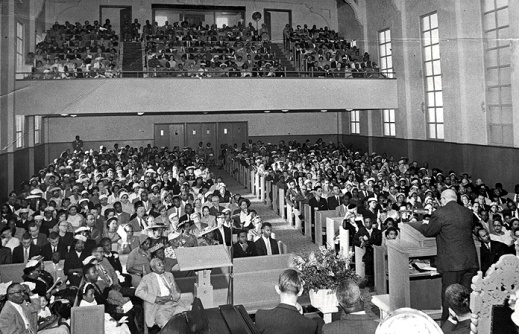

In her 1971 book His Day is Marching On: A Memoir of W. E. B. Du Bois, Shirley Graham Du Bois recalled about her late spouse’s public lectures that “everyone in that hall followed his words with close attention. Though he read from a manuscript replete with statistics and sociological measurements, he reached the hearts as well as the minds of his listeners.” Shirley’s memory about W. E. B.’s lectures invites reflection on the social and political significance of what I call his “itinerant intellectual soundscapes”—the spaces in which he spoke as an itinerant intellectual, a scholar who traveled annually on lecture tours to speak on the historical substance of contemporary events, including presentations annually during Negro History Week.

Yet Du Bois’s lectures took place within and across a soundscape he shared with an audience. In what follows, I center the sound of Du Bois’s voice literally and figuratively to 1) document his itinerant intellectual labor, 2) analyze how listeners responded to the soundscapes in which his speeches resided, and 3) explore what it means to listen to Du Bois in the present historical moment.

***

Upon completing a Ph.D. in history at Harvard in 1895, and thereafter working as a professor, author, and activist for the duration of his career until his death in 1963, Du Bois spent several months each year on lecture trips across the United States. As biographers and Du Bois scholars such as Nahum Chandler, David Levering Lewis, and Shawn Leigh Alexander document, international excursions to Japan in the 1930s included public speeches. Du Bois also lectured in China during a global tour he took in the late 1950s.

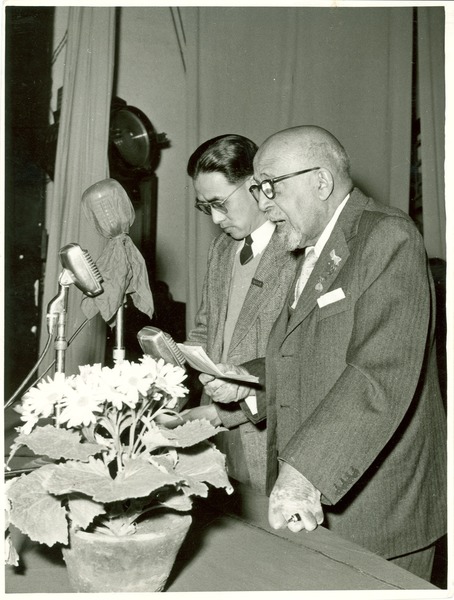

W. E. B. Du Bois delivering a speech in front of a microphone during trip to China, circa 1959, Courtesy of the Massachusetts Digital Commonwealth, physical image located in Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries

In his biographical writings, Lewis describes the “clipped tones” of Du Bois’s voice and the “clipped diction” in which he communicated, references to the accent acquired from his New England upbringing in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Reporter Cedric Belfrage, editor of the National Guardian for which Du Bois wrote between the 1940s and 1960s, listened to the black scholar speak at numerous Guardian fundraisers. “On each occasion he said just what needed saying, without equivocation and with extraordinary eloquence,” Belfrage described. “The timbre of his public-address voice was as thrilling in its way as that of Robeson’s singing voice. He wrote and spoke like an Old Testament prophet.” George B. Murphy heard Du Bois speak when he was a high school student and later as a reporter in the 1950s; he recalled the “crisp, precise English of [Du Bois’s] finely modulated voice.”

One benefit of Du Bois’s long life was its intersection with technological advances in audio recording and amplification, the dynamics of which literary historian Jennifer Lynn Stoever insightfully narrates in The Sonic Color Line. This means that in 2018 we can literally listen to Du Bois’s voice; we can experience sonic dimensions of his intellect and sit with the verbal articulation of his ideas. For example, Smithsonian Folkways released two audio recordings of Du Bois: an April 1960 speech, “Socialism and the American Negro” he delivered in Wisconsin, and a 1961 oral history interview, including a full transcript. Furthermore, in his digitized UMass archive we can read the text of another 1960 speech, “Whither Now and Why” and listen to the audio of that March lecture.

The intersection of these historical artifacts texture understanding of the textual and aural facets of Du Bois’s work as an itinerant intellectual. They give voice to specific dimensions of his late career commitments to socialism and communism and unveil the language he used to communicate his ideas about economic democracy and political equality.

The act of hearing Du Bois took place within and across his itinerant intellectual soundscape was rarely a passive activity, an experience toward which Shirley’s comments above gesture. Those who attended Du Bois’s lectures often commented on listening to his presentations by connecting visual memories with auditory recollections and affective responses.

John Hope Franklin, 1950s, while Chair of Department of History at Brooklyn College, Courtesy of Duke University

For example, the late black historian John Hope Franklin penned an autobiographical reflection about his first encounter with Du Bois in Oklahoma in the 1920s at 11 years old. At an education convention with his mother, Franklin commented on Du Bois’s physical appearance: “I recall quite vividly . . . his coming to the stage, dressed in white tie and tails with a ribbon draped across his chest . . . the kind I later learned was presented by governments to persons who had made some outstanding contribution to the government or even humankind.” He then referenced a sonic memory. “I can also remember that voice, resonant and well modulated,” Franklin wrote, “speaking the lines he had written on note cards with a precision and cadence that was most pleasant to the ear . . . the impression he made on me was tremendous, and I would make every effort to hear him in the future wherever and whenever our paths crossed.” While Franklin did not remember the speech’s content, his auditory memories deliver a unique historical impression of the sound of Du Bois’s intellectual labor—a “resonant and well modulated” inspirational voice to which Franklin attributed his own career as an intellectual and historian.

A few years after the Oklahoma lecture, Du Bois gave a February 1927 presentation on interracial political solidarity in Denver during Negro History Week. Two audience members penned letters to him in response to his speech. A minister, A. A. Heist, told Du Bois that his encouragement for interracial work across the color line was bearing fruit through community race relation meetings. Attorney Thomas Campbell’s letter, like Heist’s, confirmed the speech’s positive reception; but it also revealed captivating details about the soundscape. Campbell described the lecture as a “great speech” and a “remarkable address.” “I have never heard you deliver such an eloquent, forceful and impressive speech,” he gushed, to an “appreciative and responsive audience.” Although the speech’s text does not survive, from correspondence we learn about its subject matter and receive details about the soundscape and positive listener responses to his spoken words.

The observations of Franklin, Heist, and Campbell collectively disclose pertinent historical, gendered, and racialized dimensions of listening to Du Bois. These historical documents convey what rhetoric scholar Justin Eckstein terms “sound ontology,” the multifaceted relationship between speakers, words, listeners, and the intellectual, cultural, and affective responses generated within such sonic settings. In other words, within the context of each speech’s delivery listeners heard Du Bois speak and felt his words which generated embodied responses. At the intersection of Franklin’s visual and aural memories is a well-dressed regal Du Bois, a male black leader whose presence in Tulsa a handful of years after a destructive race riot perhaps represented recovery and resurrection, whose words and voice commanded authority. Similarly, recollections of a leading lawyer in Denver’s early twentieth-century black community lauded Du Bois’s role in fostering interracial possibility. Campbell’s admission was important; it documents how a male race leader and key figure in one of the nation’s most important interracial organizations, the NAACP, inspired through an impactful, moving, and persuasive lecture collaborative conversations across the color line. Given Du Bois’s stature as a national and international scholar and intellectual leader, Franklin, Heist, and Campbell perhaps expected him to dispense wisdom from travel and study. Nevertheless, the historical record documents an interactive soundscape that emanated from Du Bois’s presence, his words, and the listening audience.

Ethel Ray Nance, a black educator and activist from Minnesota, first met Du Bois during the Harlem Renaissance. After she moved to Seattle in the 1940s, Nance helped to organize his west coast lecture tours and assisted with his United Nations work in 1945. Nance also assembled a memoir of her work with Du Bois, titled “A Man Most Himself.” Her reflections provide a unique personal perspective on Du Bois. She recalled meeting him at a reception held in his honor after a lecture in Minneapolis in the early 1920s. She described the larger soundscape of Du Bois’s lecture, especially how listeners responded to him. “The audience gave him complete attention,” she wrote, “they seemed to want him to go on and on. You could feel a certain strength being transmitted from speaker to listeners.”

Also in Minnesota, around the same time a young black college student named Anna Arnold Hedgeman heard Du Bois lecture at Hamline University. As she listened to a lecture on Pan-Africanism with “rapt attention,” Hedgeman wrote in her 1964 memoir The Trumpet Sounds, she noticed that Du Bois wore “a full dress suit as though he had been born in it” and commented that “his command of the English language was superb.” Hedgeman located her inspiration for a career in education and activism to hearing Du Bois speak. “This slim, elegant, thoughtful brown man had sent me scurrying to the library and I discovered his Souls of Black Folk,” she said.

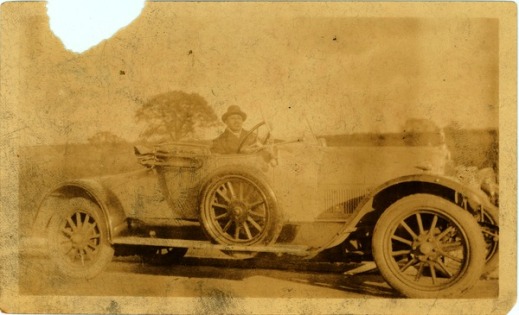

W.E.B. Du Bois on a country road in his own car, 1925, Courtesy of the Massachusetts Digital Commonwealth, physical image located in Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries

Broadly speaking, the listener responses mentioned above capture dimensions of Du Bois’s public reception at arguably the mid-life pinnacle of his career. He was in his 50s during the 1920s, an established scholar, author, and black leader. Yet due to shifting national and international conditions related to capital, labor, and civil rights during the Great Depression and World War II, his politics moved further left. He settled more concretely on socialist solutions to capitalism’s failures. This position became increasingly unpopular as the Cold War dawned. People still listened to Du Bois, but with far more critical and dismissive dispositions.

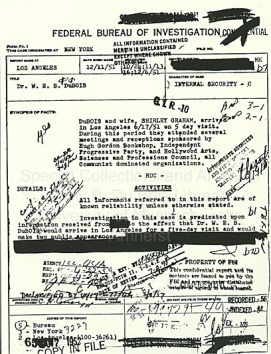

Page from W.E.B. Du Bois’s voluminous FBI file

Peering further into the historical record, part of Du Bois’s verbal archive and audible history resides in his FBI file. Concerned about his leftist political leanings, the Bureau had surveilled Du Bois starting in the 1940s by reading his publications, and dispatching agents or informants to attend his lectures and speeches. As the Cold War commenced, scrutiny increased. Redacted reports communicated his movements throughout the world in 1960, including a speech at the Russian Embassy in Washington, D. C. when he received the Lenin Peace Prize, and an address he gave in Ghana at a dinner celebrating that nation’s recent independence in 1957. The FBI file states that he received “an ovation as he rose to make a statement” about world peace and a more equitable distribution of resources. Similarly, the report from Ghana relayed that in his address he outlined two divergent world systems, “the socialism of Karl Marx leading to communism, and private capitalism as developed by North America and Western Europe.”

The bureaucratic construction of FBI reports reveals less about the audibility of Du Bois’s voice. However, unlike the listener reports presented above, the technical nature of bureaucratic communications offer a great deal more about the content of his speeches and thus documents another sense in which people—presumably FBI agents or informants—heard or listened to Du Bois as part of their sonic surveillance.

Du Bois’s audible history invests new meaning into his work as a scholar and public intellectual. Through John Hope Franklin, Shirley Graham Du Bois, and Anna Arnold Hedgeman we “see” Du Bois lecturing and speaking, in effect the public presence of a scholar we tend to know more readily through the printed words of his publications. With Thomas Campbell and Ethel Ray Nance—and from a different vantage point his FBI files—we “feel” the power of Du Bois’s words and the affective experience of his verbal constructions. Whether found in historical documents or narrated through vivid descriptions of the “clipped” aspects of his voice’s literal sound, investigating Du Bois’s audible history innovatively humanizes a towering scholar mostly readily known through his published words.

Attending to the audible and archival records of his life and times, we not only encounter the sonic dimensions of his literal voice, we observe how ordinary people listened to him and responded to his ideas. Some embraced his perspectives while others, especially during the Cold War, denounced his socialist vision of the world. Yet this is where the redactions in the FBI files ironically speak loudest: Du Bois’s ideas persisted, and survived. Scholars and activists amplified his words and retooled his ideas in service of black liberation, social justice, and economic equality.

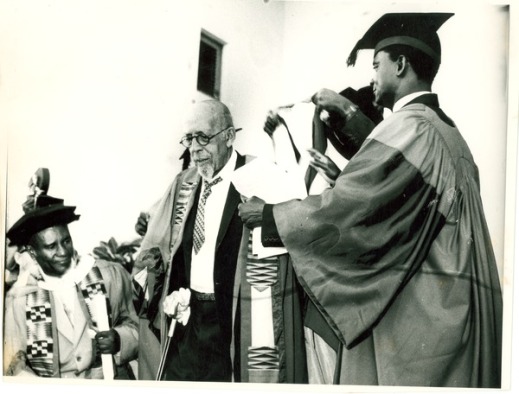

W.E.B. Du Bois receiving honorary degree on his 95th birthday, University of Ghana, Accra, 1963, February 23, 1963,Courtesy of the Massachusetts Digital Commonwealth, physical image located in Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries

By literally listening to and sitting with an audible Du Bois today there’s an opportunity to mobilize affect into action, a version of what Casey Boyle, James J. Brown, Jr. and Steph Ceraso call “transduction.” Du Bois’s voice digitized delivers rhetoric within yet beyond the computer screen. It (re)enters the world in a contemporary soundscape. Hearing his voice produces affect and thought; and thought provokes action or inspires creativity. Such a “mediation of meaning” shows that contemporary listeners inhabit a soundscape with Du Bois. Whether a scholar listens to Du Bois in an archive, students and teachers engage his voice in the classroom, or anyone privately at home leisurely tunes into his speeches, time, space, and place collectively determine how wide and expansive the Du Bois soundscape is. Advancements in communication, digital and sonic technologies mean that across whatever modality his voice moves there’s a sense in which Du Bois remains an itinerant intellectual.

—

Phillip Luke Sinitiere is a W. E. B. Du Bois Visiting Scholar at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 2018-19. He is also Professor of History at the College of Biblical Studies, a predominately African American school located in Houston’s Mahatma Gandhi District. A scholar of American religious history and African American Studies, his books include Christians and the Color Line: Race and Religion after Divided by Faith (Oxford University Press, 2013); Protest and Propaganda: W. E. B. Du Bois, The Crisis, and American History (University of Missouri Press, 2014) and Salvation with a Smile: Joel Osteen, Lakewood Church, and American Christianity (New York University Press, 2015). Currently, he is at work on projects about W. E. B. Du Bois’s political and intellectual history, as well as a biography of twentieth-century writer James Baldwin. In 2019, Northwestern University Press will publish his next book, Citizen of the World: The Late Career and Legacy of W. E. B. Du Bois.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Black Mourning, Black Movement(s): Savion Glover’s Dance for Amiri Baraka –Kristin Moriah

Saving Sound, Sounding Black, Voicing America: John Lomax and the Creation of the “American Voice”–Toniesha Taylor

The Sounds of Anti-Anti-Essentialism: Listening to Black Consciousness in the Classroom–Carter Mathes

“I Love to Praise His Name”: Shouting as Feminine Disruption, Public Ecstasy, and Audio-Visual Pleasure–Shakira Holt

This is not new to me. Both my artistic work and a number of my scholarly works have been purposely ignored or undermined in previous occasions, perhaps due to my non-white, non-European background and epistemology. During the assessment of my doctoral dissertation in a well-known Scandinavian University, for example, the three-member committee harshly attacked the very foundations of my project because of my claim that case studies in Indian cinema could produce important new knowledge in the field of sound studies, media art and film history. However, Indian cinema, the largest producer of films in the global industry, is equally a part of world cinema as European and American cinemas, and studying its sound production would indeed add dimensions to the field of sound studies. Their resistance towards my object of study implied that choosing European cinema would immediately make my hypotheses acceptable.

This is not new to me. Both my artistic work and a number of my scholarly works have been purposely ignored or undermined in previous occasions, perhaps due to my non-white, non-European background and epistemology. During the assessment of my doctoral dissertation in a well-known Scandinavian University, for example, the three-member committee harshly attacked the very foundations of my project because of my claim that case studies in Indian cinema could produce important new knowledge in the field of sound studies, media art and film history. However, Indian cinema, the largest producer of films in the global industry, is equally a part of world cinema as European and American cinemas, and studying its sound production would indeed add dimensions to the field of sound studies. Their resistance towards my object of study implied that choosing European cinema would immediately make my hypotheses acceptable. In his essay “

In his essay “

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Samantha Ege

Samantha Ege REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out: