I am not a board games person, yet I always seem to find myself surrounded by them. Such was the case one August evening in 2023, during a round of the bird-watching-inspired game, Wingspan. Released in 2019 by Stonemaier Games, designer Elizabeth Hargrave’s creation is credited with a dramatic shift in the board game industry. The game received an unparalleled number of awards, including the prestigious 2019 Kennerspiel des Jahres (Connoisseur Game of the Year), and an unheard of seven categories of the Golden Geek Awards, including Best Board Game of the Year and Best Family Board Game of the Year. In addition to causing shifts in typical board game topic, artistry, and demographic, Wingspan has led many board game fans to engage with the natural world in new ways, even inspiring many to become avid birders.

Following the game’s rise to popularity, developer Marcus Nerger released an app, Wingsong which allows players to scan each of the beautifully illustrated cards and play a recording of the associated bird’s song. On the evening in question, the unexpected occurred when I scanned the Spotted Owl (Strix occidentalis) card and received a message that read:

Playback of this birds[sic] song is restricted.

Of course, I had to know more. Although the board game was originally designed using information from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s eBird.org website, Wingsong derives its recordings from another free database, xeno-canto.org. A quick search of the website revealed the following statement:

Some species are under extreme pressure due to trapping or harassment. The open availability of high-quality recordings of these species can make the problems even worse. For this reason, streaming and downloading of these recordings is disabled. Recordists are still free to share them on xeno-canto, but they will have to approve access to these recordings.

Though Xeno-Canto does not give specific details about each recording, the Wingspan card offers a clue in italics at the bottom: “Habitat for these birds was a topic in logging fights in the Pacific Northwest region of the US.”

The unexpected incursion of such politics into a board game is startling, especially given the limited information in the initial message. As such, the restriction of Spotted Owl recordings on Xeno Canto, and by extension Wingsong, suggests complicated issues relating to the ownership and distribution of sound, censorship, and conservation.

Spotted Owl Recordings

The status of the Spotted Owl was a major issue of public debate in Oregon of the 1980s and 90s, where I grew up. As Dr. Rocky Gutiérrez, the “godfather” of Spotted Owl research, wrote in an article for The Journal of Raptor Research, “Conservation conflicts are always between people – not between people and animals” (2020, 338). In this case, concerns about the impacts of logging in old-growth forests, thought to be the primary habitat of the Spotted Owl, pitted loggers and the timber industry against conservationists. On both sides, national entities like the Sierra Club and the Western Timber Association helped turn a regional management issue into one with implications for forest protection, wildlife conservation, and economic development across the nation. Forty years later, it is still a hot button issue for scientists, industry, and the government, now with added complications of fire control, climate change, and competing species like the Barred Owl (Strix varia).

Xeno-Canto uses a Creative Commons license, meaning that users can access and apply to a wide variety of projects without explicit permission of the recordist, but it also offers tools for contacting other users. I wrote to two recordists who uploaded Spotted Owl calls to Xeno Canto: Lance Benner and Richard Webster, both recording in southern areas where the Spotted Owl’s conservation status is slightly less dire than in Oregon. Benner is a scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology, whose recordings have been used in scientific research projects, at nature centers, in phone apps, and notably, in a Canadian TV show. Benner told me via email that he agrees with Xeno-Canto’s restriction on the Spotted Owl recordings to the public, writing

I used to play spotted owl recordings when leading owl trips but I don’t any more now that the birds have been classified as “sensitive.” There have also been multiple attempts to add the California Spotted Owls to the endangered species list, so if I find them, I’m not sharing the information the way I used to….

Webster, on the other hand, offered a slightly different perspective:

There are enough recordings in the public domain that restricting XC’s recordings probably will not make a difference. However, some populations of Spotted Owl are threatened, and abuse is quite possible…

As Webster points out, numerous recordings of Spotted Owls are readily available, including via The Cornell Lab of Ornitology’s Voices of North American Owls and other audio field guides. The concern with such recordings, Gutiérrez told me over Zoom, is that anti-Spotted Owl activists might use the recordings to “call in” Spotted Owls – essentially a form of audio catfishing historically used in activities like duck hunting. In the case of Spotted Owls, the concern is that activists might deliberately harm the birds. However, it can also be a dangerous practice when used by birders who simply want to get a closer look: birds may abandon their nests, leaving chicks vulnerable and unprotected.

From a sound studies perspective, “calling in” underscores questions of avian personhood. Rachel Mundy contends that audio field guides are structured by people in ways that highlight animal musicianship. Yet when we consider the practice of “calling in,” it becomes clear that birdsong recordings are not only designed for human ears, but also avian ones.

Nonetheless, while birds are considered intelligent enough to recognize a call from their own species, they are not believed to be able to identify the difference between a recording and a live performance. The bird’s sensorium is short-circuited by the audio recording, tricking it into thinking a mate is nearby. Not only does this recall the interspecies history of the RCA Victor label His Master’s Voice, it highlights distinctly human anxieties about the role of recording and its ability to dissimulate. Restricting access to such recordings, then, revives deep-seated ethical questions that require a nuanced application.

Whether or not Spotted Owls are able to differentiate between a recorded call or the call of a live mate it is likely to be of decreasing concern, however: Gutiérrez suggests that Northern Spotted Owl populations are so small that anyone attempting to call one in would be unlikely to actually find one.

Immersion, Conservation, Reflection

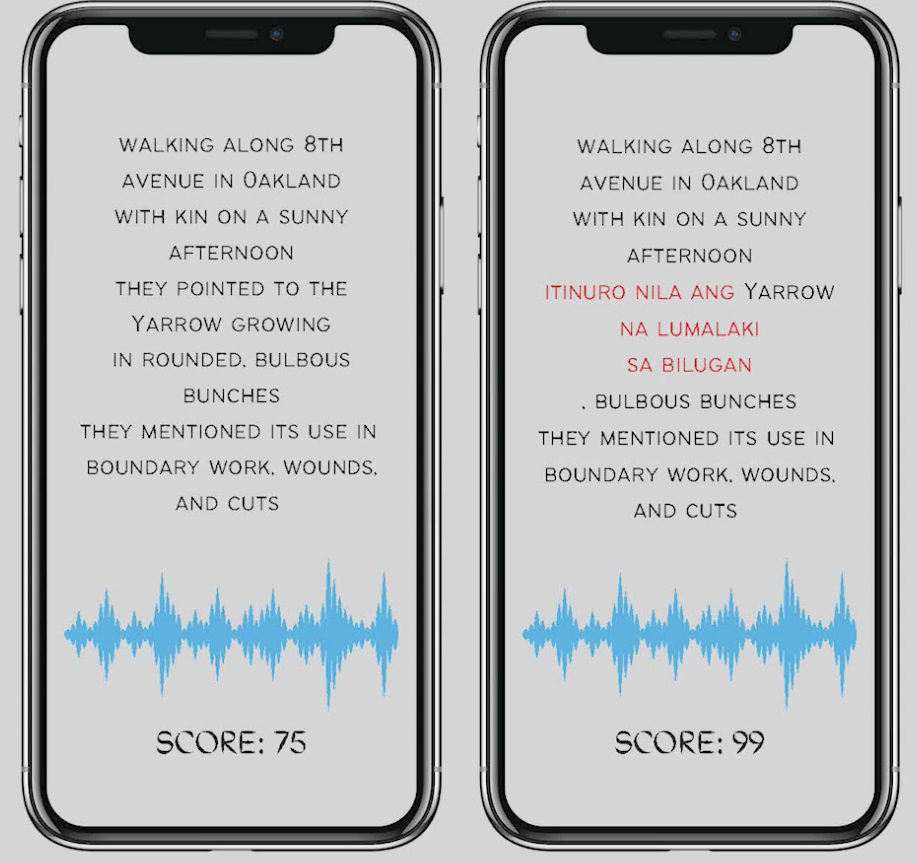

App developer Marcus Nerger conceptualizes Wingsong as part of an immersive augmented reality experience, one that situates the game player in a more realistic soundworld. In the world of board games, parallels might be drawn to audio playlists used in tabletop role playing games like Dungeons and Dragons, or to the immersive soundscape design used in video games.

Via Zoom, Nerger and I discussed the importance of sound in bird identification, which is arguably more significant than vision given birds’ general fearfulness of humans, branch cover, and the physical distance bird and observer – a separation underscored by the pervasive use of technologies like binoculars. Wingsong is not simply immersive because it connects the player to the real bird species, but because the experience of birding relies as much on hearing as it does on sight.

However, the Spotted Owl restriction message provides a provocative interruption to the immersive bird song experience provided by Wingsong. It is a jarring contrast to the benign experience of listening to recorded bird song, reminding the player of both the artifice of game play and the consequences of environmental actions. It suggests that the birds in the game are not hyper realistic Pokémon to be simply collected, but rather living animals embedded in environmental and political histories. The lack of information provided in the “restricted” message leaves the player wanting more – and subsequently, with a bit of searching, unearthing the mechanics behind the app, the politics of bird song recording, and finally, the specific histories of the species contained there, the ghost in the machine irrevocably unveiled.

—

Featured Image: by author

—

Julianne Graper (she/her) is an Assistant Professor in Ethnomusicology at Indiana University Bloomington. Her work focuses on human-animal relationality through sound in Austin, TX and elsewhere. Graper’s writing can be found in Sound Studies; MUSICultures; forthcoming in The European Journal of American Studies and in the edited collections Sounds, Ecologies, Musics (2023); Behind the Mask: Vernacular Culture in the Time of COVID (2023); and Songs of Social Protest (2018). Her translation of Alejandro Vera’s The Sweet Penance of Music (2020) received the Robert M. Stevenson award from the American Musicological Society.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Animal Renderings: The Library of Natural Sounds — Jonathan Skinner

Sounding Out! Podcast #34: Sonia Li’s “Whale” — Sonia Li

Catastrophic Listening—China Blue

Learning to Listen Beyond Our Ears: Reflecting Upon World Listening Day–Owen Marshall

Botanical Rhythms: A Field Guide to Plant Music–Carlo Petrão

The Better to Hear You With, My Dear: Size and the Acoustic World--Seth Horovitz

The Screech Within Speech–-Dominic Pettman