Post-War Surrealism and Anti-authoritarianism

Thinking Face Emoji season 1 is out!

We are excited to share all of the episodes of Thinking Face Emoji, a podcast miniseries by The Hmm, in collaboration with the Institute of Network Cultures, and supported by the Creative Industries Fund NL.

In this inaugural episode of Thinking Face Emoji, Margarita Osipian and Sjef van Beers from The Hmm, are joined by Sam Cummins, of Nymphet Alumni, to discuss the girlboss. Overly familiar with the many critiques this online stereotype has gotten over the years, we shift our focus to look at the cultural and aesthetic environment that led to the girlboss, her inception, and the impact she made on our (online) culture today.

Mentioned in this episode:

What is a Girlboss? | Netflix

Ban Bossy — I’m Not Bossy. I’m the Boss.

Beyoncé at the 2014 MTV Video Music Awards

That Feeling You Recognize? Obamacore.

What Do Students at Elite Colleges Really Want?

Nymphet Alumni Ep. 113: Information Age Grindset w/ Ezra Marcus

All-woman Blue Origin crew floats in space

In Space, No One Can Hear You Girlboss

Find Sam and Nymphet Alumni at:

Instagram

Nymphet Alumni

Instagram – Nymphet Alumni

In this episode Salome Berdzenishvili, from the Institute of Network Cultures, and Sjef van Beers, from The Hmm, talk to Dr. Daniël de Zeeuw, from the University of Amsterdam’s department of Mediastudies, about how terms originally associated with incel and femcel communities seem to have reached the mainstream.

Mentioned in this episode:

“‘Teh Internet is Serious Business’: On the Deep Vernacular Web Imaginary and its Discontents”

Based and confused: Tracing the political connotations of a memetic phrase across the web

Find Daniël at:

Bluesky

uva.nl

In the third episode of Thinking Face Emoji, Margarita Osipian from The Hmm and researcher Mita Medri, are joined by writer and cultural commentator Ana Sumbo, to discuss the online phenomenon of looksmaxxing. Hunter vs prey eyes, the canthal tilt, siren vs. doe eyes, angel vs witch skull, or a FYP filled with Gigachad jawlines. This is the landscape, or some might say cesspool, of looksmaxxing. With its incel-verse undertones and radical history, we discuss whether this phenomenon is just another glow-up trend or is it signaling a resurgence in eugenics?

Mentioned in this episode:

“men used to go to war” | TikTok clip from Kareem Shami

The Slow Burn Back to Eugenics by Ana Sumbo

The Digital Legacy of Eugenics project by Lila Brustad

Rage against the machine: how incel culture went mainstream in 2023 by Günseli Yalcinkaya

Predatory Data: Eugenics in Big Tech and Our Fight for an Independent Future by Anita Chan

I tried all of the most popular looksmaxxing glowup tips! | TikTok clip from Michael Hoover

Deathnics thread on looksmax.org

Yassified Eugenics by Abha Ahad

POV: How the SS officers pulled up to the Nuremberg trials | TikTok clip from Kareem Shafti

Are you the hunter or the hunted? | Instagram video from @rawreturned

Lard of estrogen | Instagram video from @nickfraserrrrr

Find Ana at:

Substack

In this episode, Maja Mikulska from The Hmm and Anielek Niemyjski from the Institute of Network Cultures are joined by Maya B. Kronic – co-author of Cute Accelerationism and Head of Research and Development at Urbanomic – to discuss all things Sock. From Bushwick enbies to memes and fancy foot cover-ups, the conversation focuses on what it means to explore gender nonconformity, both online and offline.

Mentioned in the episode:

Having roommates in Bushwick be like

Logged On podcast episode with Maya

NB names be like

Demi Lovato being nonbinary for less than a year

Gender adventure TikToker

Enby barista trend

Socks in queer experience

Zettay Ryouiki

Find Maya at:

readthis.wtf

In the fifth episode of Thinking Face Emoji, Margarita Osipian from The Hmm and Anielek Niemyjski from the Institute of Network Cultures are joined by writer and independent researcher Salome Berdzenishvili, to discuss the online aesthetic of the post-Soviet sad girl. Together they dissect the sad girl industrial complex to explore how this aesthetic emerged, and how it shapes and reflects the visual and emotional archives of Soviet and post-Soviet eras.

Mentioned in this episode:

Лана Дель Рей – Летняя Печалька – Lana del Ray Summertime Sadness with voiceover

Girl Online – Symposihmm playback

Preliminary Materials For a Theory of the Young-Girl by Tiqqun

Becoming and Unbecoming – Eastern European Girlhood Online by Salome Berdzenishvili

Moy Marmeladny trend on TikTok

#Slavic Core – TikTok

Clean girl in a post soviet country TikTok by Sh.Sayadze

How to Become as Intimidating Yet Visually Striking as Brutalist Architecture by Sumayya Bisseret Martinez

Mental health walk in Eastern Europe TikTok trend

Eastern European girlhood on Instagram, bikini in puddles compilation

Find Salome at: networkcultures.org/blog/author/salome/

In the sixth and last episode of the season we delve into the future of girlhood in online culture. Since 2023, the so-called “year of the girl” with trends like girl math, girl dinner, and the Barbie movie’s influence, girlhood has become a widely discussed cultural and theoretical concept. We’ve learned that the figure of the girl has evolved into a digital strategy rather than a fixed identity, one that is shaped by algorithms, aesthetics, and performance. Together with one of the initiators of @everyoneisagirl Ester Freider, Lilian Stolk from The Hmm and Mela Miekus from the Institute of Network Cultures explore how femininity is performed online and the end of identity.

Mentioned in this episode:

Pinkydoll’s NPC TikTok live

“Everyone is a Girl” by Alex Quicho

@everyoneisagirl on Instagram

Ghosted 1996 on Instagram

Sighswoon on Instagram

“Networks and Their Discontents“ by William Kherbek referenced in “I’m Like a Pdf But a Girl“ by Ester Freider

“Side-eyeing the cyberbaroque“ by Ester Freider

“Hallucinating sense in the era of infinity-content“ by Carolina Busta

Princess Substack highlights

Find Ester at: Instagram Linktree

Thinking Face Emoji is a podcast by The Hmm, in collaboration with The Institute of Network Cultures, and financially supported by the Creative Industries Fund NL.

Jingle and sound design by Jochem van der Hoek.

Editing by Salome Berdzenishvili.

Cover art by Aspirin.

Looking forward, looking back: William Moorcroft in the news

By Jonathan Mallinson

Within the space of just five days in June this year, William Moorcroft was twice in the news. One item recorded the sale at auction (for a record-breaking price) of a particularly rare example of his ceramic art. The other reported the rescue from liquidation and the return to family ownership of his pottery works in Burslem.

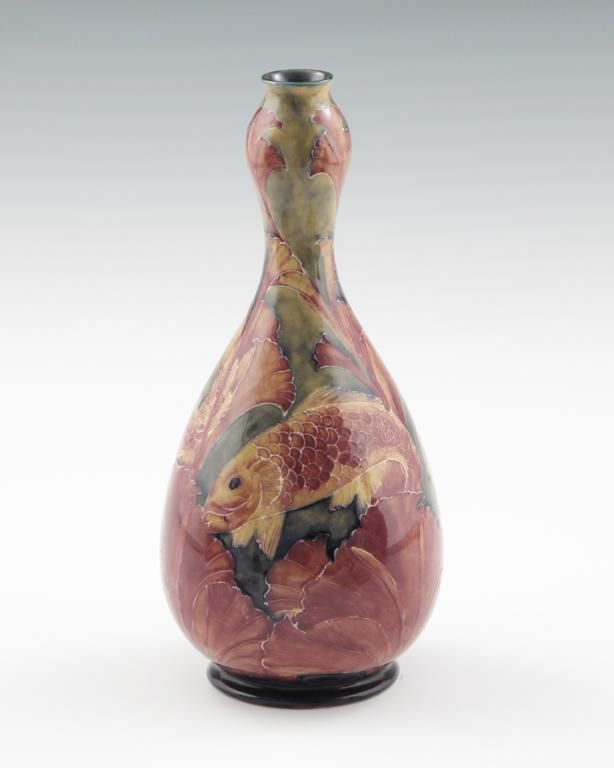

The vase, in double gourd form, is decorated with carp, swimming through reeds in an eye-catching palette of red and ochre. The object is indeed rare; only three others, similar but not identical, are known to exist. Its significance, though, derives not just from its rarity or its current market value, but from the circumstances of its creation.

It dates to 1914, the year following Moorcroft’s move to his own works from J Macintyre & Co, where he had been employed as Head of Ornamental Pottery since 1897. This was a turning point in his career, the outcome of increasingly tense relations with the firm’s General Manager which had resulted in the closure of his department. It was a moment of liberation, the opportunity to create pottery entirely on his own terms, with the small devoted team of co-workers (as he called them) which followed him from Macintyre’s. Designed and built in less than six months of intense activity, these new works were the mark of his determination and self-belief, clearly seconded by Liberty’s who co-funded the project.

What more appropriate motif to capture the import of this moment than that of the carp, symbol of perseverance and courage, whose arduous journey up the Yellow River to a famed waterfall cascading down from the Dragon’s Gate was the stuff of Chinese legend. Any carp strong or brave enough to make a final leap over the waterfall would be transformed into a dragon, but such an exploit was rare.

Moorcroft’s vase recalls high points in his earlier career. The carp motif featured in a limited series of vessels made at the turn of the century, when his innovative Florian ware was generating exceptional critical acclaim; and its distinctively rich palette characterised some of his last (and most successful) designs at Macintyre’s. But there is nothing celebratory about this pot, for all that Moorcroft’s move to Burslem represented a remarkable triumph over adversity. It depicts carp, after all, not a dragon; it suggests a journey, not a parade. And this is not surprising for an artist who already, in his professional and personal life, had experienced multiple challenges and setbacks. And more were to come. His first year at Burslem was beset by practical problems of different kinds; and others, global and uncontrollable, were on the horizon, extending unforeseeably far into the future. But for Moorcroft, challenge was creative, adversity was there to be overcome. As he wrote to his daughter on 17 October 1930, just short of a year after the Wall Street crash: ‘I feel that difficult times are with us, to force the best out of us. We do better work when we are faced with something to fight against’. This pot is characteristic of that creative response, a profession of faith, a statement of intent to turn adversity into art.

It is an exceptional vase in many ways, but it offers, too, a broader insight into Moorcroft’s vocation as a potter. Evidently not made for commercial production, this evocative object was, nevertheless, sold (or gifted), reputedly acquired by its first owner as a wedding present in the year it was made. And what is true of this piece is true of his art as a whole. Moorcroft’s pots were clearly made for sale, but they were not conceived as (merely) commercial commodities. His enduring ambition was to express in clay his personal response to the world about him, his sense of beauty, and to share it with others. Writing to his daughter on 20 November 1930, he put this into words: ‘ I feel there is a need for interesting, individual things. […] We want pleasant things to live with. Not extreme, not fashionable, but things that will be the outcome of careful thought, things built with the spirit of love in every part of them’. And such objects were not confined to those with the highest monetary value. One hundred years before this record-breaking sale, the Pottery Gazette of September 1925 reported that the then exceptional sum of £100 had been offered for ‘a single piece’ of Moorcroft’s pottery, displayed at the British Empire Exhibition the year before. But this was just half the story of the potter’s appeal, as the critic observed: ‘we are just as much comforted by the thought that even a simple and tolerably inexpensive piece of Moorcroft ware is regarded by thousands of people as a priceless possession’.

That Moorcroft’s work is still highly valued today tells us something about the capacity of his very personal art to reach out across time, but also, more generally, of the continued need for ‘interesting, individual things’. The post-pandemic world of 1930, in the grip of escalating political tension and economic uncertainty, is not without similarities with our own. How fitting, then, that a vase which so powerfully exemplified Moorcroft’s guiding principles at the birth of his new works, should surface, however briefly, in the same week that this same factory, which had long continued to make pottery to the designs of his son, Walter, before passing out of family hands, had been bought by William’s grandson. An encouragement like no other at the start of this new journey to the Dragon’s Gate.

'William Moorcroft, Potter: Individuality by Design' by Jonathan Mallinson is an Open Access title available to read and download for free or to purchase in all available print and ebook formats at the link below.

Slop Cinema: The Work of Art in the Age of Computational Hallucination

Infidels claim that the rule in the Library is not ‘sense;’ but ‘non-sense;’ and that ‘rationality’ (even humble, pure coherence) is an almost miraculous exception. They speak, I know, of ‘the feverish Library, whose random volumes constantly threaten to transmogrify into others, so that they affirm all things, deny all things, and confound and confuse all things, like some mad and hallucinating deity.’ Jorge Luis Borges, The Library of Babel

Total Pixel Space

Total Pixel Space is a nine-minute video work by filmmaker and composer Jacob Adler [1]. In May 2025, it won the grand prize at the third international Runway Artificial Intelligence Film Festival (AIFF) in New York City. Runway is a commercial generative AI (GenAI) platform, so it’s not surprising to find on the AIFF website optimistic language such as:

“Works showcased offer a glimpse at a new creative era. One made possible when today’s brightest creative minds are empowered with the tools of tomorrow” [2].

Produced entirely with Runway 3’s text-to-video generator, Jacob Adler’s Total Pixel Space comprises a variety of dreamlike, slow-moving, surrealist scenes in a uniform muted colour palette. An AI-generated soft woman’s voice narrates the essayistic script, reflecting on the unfathomably vast, yet finite, possible combinations of pixels that could produce images and films. Behind the narration is a pensive piano soundtrack composed by Adler, whose practice is predominantly composition and music production.

For the most part, the scenes in Total Pixel Space operate with a quasi-photographic visual language typical of the GenAI output circulating social media—the kind we might notoriously refer to as AI slop. Unlike the Invisible Images produced by media artist Trevor Paglen [3], Adler had clearly made no attempt at undermining the production logic of GenAI or pushing GenAI forward as a medium. For this reason, the aesthetics of the film aren’t particularly striking or innovative, but they do serve a metatextual function of presenting a GenAI film as a temporal assemblage of “readymade” footage. Further, I would suggest that presenting scenes like an impersonal montage with limited artistic intervention is true to form for the medium itself: a medium that exists somewhere between found and produced footage. The film, then, becomes less about showcasing the cinematic use cases and potentials for GenAI—and, indeed, less a celebration of the technical prowess of GenAI—and more about demonstrating what GenAI looks and feels like. GenAI-core.

Entering the Library

The combination of montaged footage, an essayistic script, and disembodied narration indicates that the formal qualities of Total Pixel Space have more in common with an Adam Curtis documentary film than with a work of short fiction. This is complicated by the fact that the film obviously contains no real events, and is instead based on The Library of Babel, a short story and thought experiment by Jorge Luis Borges [4]. (As an aside, a digital recreation of the Library can be viewed here) [5]. In The Library of Babel, the narrator exists in an incomprehensibly large library—interchangeably referred to as a “universe” within the text—which contains every possible book that could ever exist within the parameters of uniform physical dimensions, 410 pages, and an alphabet comprising 22 characters and three grammatical marks. In this library, the number of books that exist is impossibly vast, yet technically finite. Some characters in this universe realise that there must exist books that explain away and vindicate all of their sins, and these characters drive themselves mad trying to find them. Some characters express frustration at the number of books that contain complete gibberish and purge thousands of them from the library altogether. The narrator explains that no matter how many books are purged from the library, such actions would be futile given the library’s size and the existence, somewhere, of another book identical in content save one or two characters. Some characters go mad contemplating the fact that while some books can reveal truths and secrets of the world, others would reveal falsehoods and fabrications, and it would be impossible to differentiate. Reality begins to disintegrate.

Published in 1941, The Library of Babel serves as an allegory for humanity’s attempts at scientifically understanding the universe itself, which is generally accepted to be comprised of a limited number of elements on an atomic scale. Ultimately, Borges suggests through this text that understanding the universe is an exercise in futility and most of it will remain unknowable forever. Adler largely does away with the allegorical quality of Borges’ story and instead discloses how the story parallels an actually-existing Library—the total possible number of pixel combinations in an image of a given size. In doing so, Adler’s reinterpretation of Borges’ story suggests that every possible image that could ever exist is already pre-determined inside “total pixel space,” and all our attempts at image generation, be they photographic or AI-generated, are merely attempts at selecting the order in which these pixels ought to be arranged. In Borges’ story, the library—although obviously fictitious—is physical; it has mass, it contains books on shelves, and it is traversable by people within the universe. Adler flips this around: total pixel space is demonstrably real insofar as pixels are real, and Adler performs a perfunctory calculation of how many images and films could possibly exist in a 1024×1024 pixel resolution. However, total pixel space, rather than being a physical space, is abstract and exists as a realm of possibilities.

The Library of Babel or the Plane of Immanence?

As a concept, total pixel space can be thought of as an analogue to Deleuze and Guattari’s plane of immanence: a metaphysical field of pure potentiality from which all things emerge and self-organise into forms and objects. In A Thousand Plateaus [6], Deleuze and Guattari describe this as such:

“In any case, there is a pure plane of immanence, univocality, composition, upon which everything is given, upon which unformed elements and materials dance that are distinguished from one another only by their speed and that enter into this or that individuated assemblage depending on their connections, their relations of movement. A fixed plane of life upon which everything stirs, slows down or accelerates” [6, p. 255].

The similarities between total pixel space and the plane of immanence are immediately apparent, especially in the context of how GANs generate images by sifting noise into legible and ordered forms. One can imagine the aforementioned quote describing the dance of random pixels being sorted according to a computer user’s GenAI input prompt into a picture. Along the lines of this analogy, we have two premises that must be considered. Firstly, there is the premise central to Adler’s video work, that total pixel space contains the latent potentiality for every image that could possibly exist. Secondly, and much more crucially, is the premise that the plane of immanence is that from which all things become. This brings me to one more important difference between Borges’ The Library of Babel and Adler’s Total Pixel Space.

If we recall that in Borges’ story, characters go mad from contemplating the vastness of the library and the untrustworthiness of the books within, then we have a cure in Total Pixel Space that mirrors the search for meaning in the post-truth era. This rests on comparing total pixel space not to the Library, but instead, to the plane of immanence. To consider total pixel space not as an impossibly vast physical library, but as a plane of immanence, reveals a subtle implication for the way images are understood within Adler’s work and in the post-truth era more broadly. Images, understood against the backdrop of total pixel space, are not Baudrillardian simulations of the real, but reifications of things that could exist. Something becomes real when it emerges from the plane of immanence. The narrator in Total Pixel Space suggests at 3 minutes 14 seconds, “when we take photos, perhaps we are not creating images—we are merely navigating to their predetermined coordinates, like travellers arriving at destinations that were always there,” and at 6 minutes 2 seconds, “most regions [in total pixel space] appear as noise to our eyes, but perhaps they hold patterns our brains aren’t wired to see” [1]. Although poetic, this way of framing images as things that could be real is acutely compatible with the epistemic structure of post-truth. It speaks to the uncertainty of the ontology of things people encounter on their screens, and to the notion that in the post-truth era, an image of something—of anything—is as real as it gets. Rather than going mad at the unreliability of books in the Library, we have the condition where whatever we create becomes real by virtue of it being created.

Despite that the aesthetics of Total Pixel Space are technically not dissimilar from AI slop, the footage is produced and montaged with enough specificity and deliberation that it merits its own analysis. The film begins with, and maintains throughout, black title cards with pale yellow italic and sans serif text shaking gently as if they belonged to a silent film from a century ago or an at-home slide projector. Immediately after, we see a family sitting in front of the TV in a scene which ought to be understood as “retro” or vaguely resembling the 1950s. Then, a large cat on a girl’s lap as she sits in front of a piano, smiling at the camera, colours shifted to emphasise reds and magentas in the shadows and cyans and yellows in the highlights, evoking a photograph from the 1970s faded from years of sun exposure. This faded colour grading permeates the entire film, save for moments when pops of bright oranges, pinks and turquoises break through the otherwise nostalgic palette.

Throughout the film, instances of surveillance cameras or futuristic alien robots appear, each depicted with extremely large and round lenses meeting the viewer at eye height. These lenses resemble the kind of neotenous—i.e. cute—cartoonish eyes typically used to portray animals, but occasionally also robots such as Disney-Pixar’s Wall-E. In other scenes, we have a room filled with an overstimulating number of beige plastic computers which could also pass as microwave ovens, each of them overflowing with a constant stream of flashing content and monitored by a single person in the centre of the visual field. The combination of an overstimulation of onscreen content and late 20th century computer aesthetics is but one example of the work’s temporal confusion, or what I might refer to instead as atemporal nostalgia.

The atemporal nostalgia continues throughout the film, with various scenes involving anthropomorphic animals wearing block colour cardigans or button-down shirts—the kind that were popular in the early 2010s because of their vintage stylings. In fact, these depictions themselves have a decidedly retro appearance in a video produced in 2025, passing aesthetically for the twee ‘hipster’ tropes one would typically expect from the same early 2010s cultural touchstones. Animals appear frequently throughout the film—when they aren’t anthropomorphic, they are large, ambiguously both alien-like and earthen, and met by humans either photographing them or reaching out to them with their hands. These scenes evoke a kind of “close encounter,” suggesting not humanity’s brush with the future per se, but with an alternate reality itself. These animals, symbols of this alternate reality, are often depicted as graceful, passive and majestic, either indifferent to the humans approaching them or existing solely for the zoological gaze of the human subjects in the film. The inclusion of these animal scenes suggests that GenAI is the medium, or conduit, through which we humans can have this encounter with an alternate reality; one which is already waiting there for us to explore. If the viewers of this work were to identify with the human subjects onscreen, it would resemble the spiritualist dynamic some people have towards LLMs, evident throughout a swathe of subreddit posts [7], [8], claiming that an LLM contains some kind of consciousness that we could unlock by speaking to it the right way.

Sometimes the atemporal nostalgia has a more explicitly scientistic affect. Two scenes depict anonymous lecturers scrawling elaborate and nonsensical mathematical equations across blackboards; they’re not meant to be understood, they’re meant to evoke 20th century theoretical physicists at work. Perhaps they are laying the groundwork for the discovery of black holes, or perhaps for the atomic bomb—both belonging to what I might describe as a scientific sublime within popular culture. This scientific sublime continues with an image of a nebula in space, and a variety of depictions of rocky alien landscapes akin to the images retrieved from Japan’s successful mission landing two rovers from the Hyabusa2 spacecraft onto the Ryugu asteroid in 2018 [9], [10].

The scientific sublime scene that is perhaps the most revealing of the limits of GenAI is the depiction of spacetime curvature. Spacetime curvature is often depicted as a funnel shape covered in a grid system—this is a metaphorical depiction which serves to explain Einstein’s theory of gravity. In Total Pixel Space, the AI-generated imagery conceives of this curvature as a physical celestial object, moving slowly through space, reflecting light and shadow and containing a slightly rocky textured surface. As a celestial object it ambiguously resembles either a spaceship or a giant asteroid; like much of the imagery in the film, it is somehow both synthetic and organic. Depicting spacetime curvature as a physical celestial object demonstrates a fundamental quality (and perhaps a flaw) of GenAI image production and semiotics: it is incapable of operating in metaphors and has an indexical relationship to its input prompt. Even a highly abstract idea gets a literalist treatment.

Post-Truth Art

The conventional understanding of post-truth, if the Oxford English Dictionary can serve as such a benchmark for this, is that it describes “circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping political debate or public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief” [11]. This is a rudimentary understanding, so it would be more helpful, instead, to offer a definition of post-truth that acknowledges the structural conditions that enable why these emotional appeals are becoming increasingly salient in the first place. Towards this, media theorist Ignas Kalpokas claims that post-truth is the inevitable condition brought about by the near-total mediatisation of experience [12]. Following Kalpokas’ definition, we can appreciate how transformative the impact of networked technology has been upon our lifeworlds: when we interface predominantly with what Vilém Flusser calls “technical images,” communication itself functions in an entirely novel way [13]. Meaning becomes more connotative than denotative, and reality becomes fragmented and individuated.

Despite its rise to prominence in 2016 following both Donald Trump’s first election and the success of the Brexit campaign, the post-truth era does not have a discrete historical starting point, and many of the features of the post-truth era were developing over years if not decades already. Such features include propaganda disseminated through mass media, simulacra and image culture supplanting the real, the privileging of the coherence theory of truth, and the weaponisation of affect towards communicative or persuasive ends. The quality that separates the “post-truth era” from the sum of its parts must be the open admission and cultural acceptance that each of these features can be exploited, and that reality itself is far more fluid and malleable than it is concrete. If this sounds like a rehashing of postmodernism or “Gen X nihilism” then a key difference must be noted: the instability of reality itself means that our lifeworlds have become ontologically insecure [14], [15]. And this ontological insecurity means that various cohorts in society have started to search for meaning, truth, and authenticity all over again. Thus, the post-truth era is the era where truth not only gains a renewed importance after postmodernist superficiality, but that truth is now individualised, personalised and fragmented. Truth is whatever feels true, whatever you want it to be.

I reiterate that this post-truth era is largely thanks to the near total mediatisation of society, allowing for rapid spreads of misinformation, individualised media and advertising consumption, and anyone with access to a phone and the internet to reinvent themselves or gain a parasocial following. Further, I suggest that these conditions of intensified mediatisation, which have thrown consensus reality into freefall, are also responsible for the cultural normalisation of GenAI.

Sometimes artworks emerge that attempt to grapple with the impact artificial intelligence has had on our new epistemic environment. And sometimes, these artworks reveal themselves to be more symptomatic of the post-truth era than they are contemplative. Total Pixel Space, being one of these works, received a modest amount of viral attention this year. Its poetic qualities owe more to its source material in Borges’ Library of Babel, and its affectively compelling qualities owe more to the scientific sublime it relies upon. In either case, and this time owing to the GenAI medium itself, both of these ideas are taken quite literally. The literalist treatment of poetic and metaphorical ideas within Total Pixel Space pairs comfortably with its central premise, that maybe every possible image always-already exists somewhere out there. The film, dealing with a series of what-ifs, deliberately blurs the boundary between image and reality, between past and future, and between agency and passivity. It carries an optimistic tone to the idea that not only is anything possible, but anything could be real so long as it could be imaged. Receiving the grand prize at the Runway International AIFF might demonstrate its resonance and appeal amongst people with a vested interest in legitimising GenAI usage through what we might call “art-washing,” but for all the critical attention I have given it, I ultimately consider it as an example par excellence of post-truth art.

—

Paul Sutherland is PhD candidate and visual culture researcher at Curtin University, Western Australia.

References

[1] J. Adler, Total Pixel Space. 2025. Accessed: Aug. 13, 2025. [Single channel video]. Available: https://www.shortverse.com/films/total-pixel-space

[2] “AIFF 2025 | AI Film Festival.” Accessed: Sept. 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://aiff.runwayml.com/

[3] T. Paglen, “A Study of Invisible Images.” Metro Pictures, New York City, 2017. Accessed: Sept. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.metropictures.com/exhibitions/trevor-paglen4/selected-works

[4] J. L. Borges, The library of Babel. London: Penguin Classics, 2023.

[5] J. Basile, “Library of Babel,” Library of Babel. Accessed: Sept. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://libraryofbabel.info/

[6] G. Deleuze and F. Guattari, A thousand plateaus : capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

[7] ciarandeceol1, “What is going on here?,” r/HumanAIDiscourse. Accessed: June 30, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.reddit.com/r/HumanAIDiscourse/comments/1lnp2lg/what_is_going_on_here/

[8] Zestyclementinejuice, “Chatgpt induced psychosis,” r/ChatGPT. Accessed: Aug. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.reddit.com/r/ChatGPT/comments/1kalae8/chatgpt_induced_psychosis/

[9] A. Beall, “How Japan’s hopping rover nailed the first ever asteroid landing,” Wired, Sept. 26, 2018. Accessed: Aug. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.wired.com/story/japan-ryugu-asteroid-landing-rover/

[10] P. K. Byrne, “Touching the asteroid Ryugu revealed secrets of its surface and changing orbit,” The Conversation, May 07, 2020. doi: 10.64628/AAI.7djys39sx.

[11] Oxford English Dictionary, “post-truth, adj.” Oxford University Press, July 2023. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/3755961867

[12] I. Kalpokas, A Political Theory of Post-Truth. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-97713-3.

[13] V. Flusser, Communicology: mutations in human relations? in Sensing media (Series). Piraí: Stanford University Press, 2022. Accessed: July 14, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/PublicFullRecord.aspx?p=30058675

[14] R. D. (Ronald D. Laing, The divided self : an existential study in sanity and madness. in Pelican books. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1965.

[15] K. Gustafsson and N. C. Krickel-Choi, “Returning to the roots of ontological security: insights from the existentialist anxiety literature,” European Journal of International Relations, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 875–895, Sept. 2020, doi: 10.1177/1354066120927073.

The Vibe-ification of Functional Imagery

There’s something very appealing about a car crash. Morally speaking, that’s a very shitty sentence, but damn, David Cronenberg made a whole movie about it. Outside of rather unfortunate timing in a live situation, one might witness this kind of a scene through highway surveillance footage, old vehicle operating safety videos, or caught by a dashcam. These images are meant to document and inform in some way; they are operational. But they’re also images of high emotion – they often involve the risk of danger and leaving the confinements of the law; therefore, there’s an instinct of wanting to see them, like a house on fire, robbery, a high-speed chase, elevated by the voyeuristic eye of the camera. A view typically reserved for certain individuals, giving the impression that having access to this perspective is exclusive – the eye of God, the Panopticon. For the generations alive today, it’s more familiar to consider these events from a sensationalized standpoint rather than a factually documented one. There might’ve been a period when crime was reported in order to simply ‘spread the news’, but by the time OJ Simpson’s infamous high-speed car chase rolled around, the general public’s eyes were glued to their TV screens watching the white Bronco from a helicopter-view, not just for the sake of ‘knowing’.

It’s precisely this voyeuristic pleasure that spawned hour-long car crash compilations on YouTube. Imagery from movies of almost-crashes and cars generally driving recklessly are used to convey and evoke a high-strung rush in, for example, an IDLES music video for the song aptly titled ‘Car Crash’. The current top comment under the video reads: “This makes me feel so powerful and confident…like I could send a mildly confrontational email without crying.” Cronenberg’s Crash (1997) is also heavily mood-boarded on Tumblr.

One can outline a trajectory forming of the image: from operational → sensational, provocative, fetishized → What’s next?

On a slightly different note, Instagram.

Though it’s commonly believed that it has fallen far from the height of its popularity, it still allows for what used to mainly be called ‘trends’ – aesthetics and micro-aesthetics – to surface at incredible rates, to the point where some have already deemed the latter dead soon after its materialization, due to being rooted in consumerism and the speed at which it cycles onward. The aesthetic abundance also loosens the rigidity of the framework, problematizing critical thinking.

Aestheticizing something seemingly ‘unaestheticizable’ is not a new concept (which means that everything is aestheticizable, depending on your moral stance, I guess), yet it’s something worth exploring.

Gorpcore archival brand PASTDOWN has created an ad on Instagram using clips depicting different scenarios, some of them shot as if they’re recorded on CCTV. In the first one, a car crashes into anti- parking poles and a comical amount of passengers scurry out of the vehicle. In the second clip, a person runs up to an ATM machine, kicks it and money starts aggressively pouring out. In the last video, a series of jackets tied to one another is let out of a window of an apartment complex, and another hooded man climbs down and runs away, all of this depicted as blurrily-pixelated (as-if) surveillance footage.

Screenshot (slide 1/5) from archival brand PASTDOWN’s campaign ad (2024)

Screenshot (slide 2/5) from archival brand PASTDOWN’s campaign ad (2024)

Screenshot (slide 5/5) from archival brand PASTDOWN’s campaign ad (2024)

These particular clips have common threads – in all of them, what’s committed could either be permissible as a crime or at least a nuisance, or the act naturally seems like it’s connected to something nefarious. The view that’s intentionally made to resemble one of a surveillance camera at a streetcorner lamppost or above and besides an ATM provides a voyeuristic look onto a sensational- seeming but staged event. The vintage hoodies of PASTDOWN hide the identities of the supposed perpetrators, stylizing their anonymity and the act itself.

This post references an ongoing advertising trend (on Instagram, particularly), that sells consumers a product in a seemingly effortless, natural way. In trying to sell clothing, food and drinks, homeware etc., one will see clips of people in a ‘natural habitat’ that’s elevated and aestheticized thanks to the product. One can imagine a video of a sunny cafe terrace table with beautiful cocktails and dishes, enjoyed by well-dressed, grinning influencers – advertising a new, local, must-see spot.

In the case of PASTDOWN, the product is actually depicted in what could be called non-standard situations. Certainly, this imagery won’t speak to every crowd, but this is the point, of course. The images, portrayed specifically through the lens of surveillance, attract attention (in the same way a real car crash would) and only afterwards reveal themselves as advertising. When a brand intentionally inserts itself into these contexts, it is glamourizing and aestheticizing an otherwise ‘unattractive’ circumstance.

The situations created here are actually a somewhat aggressive and provocative response to the Instagram trend of advertising through situating products in various natural-seeming contexts, that simultaneously complies with its commercial framework. While the advertisement of a product could potentially elevate the life portrayed in the fake scenes, like in a video of a well-dressed girl sipping coffee on a sunny terrace, the insertion of vintage clothing within crime-esque scenarios offers a Sex- Pistols-chain-smoking-not-listening-to-your-mom-type of ‘coolness’ to these everyday-like scenes. Only, they’re not as innocent or socially acceptable as having a coffee.

Though operational images are functional, they are still designed to be so . While some aesthetics rise from categorizing values in a way that sees beauty in the apparently unbeautiful, this is a case in which it’s important to note that designing a working image requires the designer to work within an aesthetic (that stems from a practice). This makes sense since the aesthetic guidelines serve the functionality of the media. In the case of surveillance imagery, the operational image loses its functionality thrugh its decontextualization and application of mimetic aesthetics for the purposes of pure visual pleasure, or for the purpose (maybe a contradictory word to use) of disinterested pleasure. In a (Edmund Burke-ian) way, it goes from sublime to beautiful.

What is meant to be said here is that a gap should be considered between a ‘working aesthetic’ derived from and for a function, and a ‘spontaneous aesthetic’ – the users and audience of which don’t seem to concern themselves with a background check.

What actually ends up happening is a ‘re-operationalization’ of sorts. The aestheticization of surveillance footage de-functionalizes it (or at least adds an unnecessary element) in the context of its purpose, and reconfigures its aesthetics for commercial ends. Surveillance has inherent militaristic roots, and by applying this to the visuals of advertising, it normalizes and dulls down the perception of this imagery, meaning that the aesthetic pseudo-utility de-militarizes it, but, in the context of the Instagram campaigns, certainly commodifies it.

The concept of re-operationalization can extend elsewhere.

It’s widely understood that during the Soviet era, the countries taken over by the occupational force were severely censored in just about every way, with a heavy hand over the cultural sector. Multiple genres of music were forbidden, songs written by individuals were also prohibited to be played or performed, or they had to go through the Union of Soviet Composers, a division of the Ministry of Culture, which would often end up changing the songs entirely or completely cutting the chord on them. This also means that specific bands from inside and outside the borders were banned – including, at the time, The Beatles, Pink Floyd, and The Rolling Stones, for example.

Around the 1950s, and embraced by the Stilyaga subculture, emerged the so-called ‘ribs’ and ‘bone music’. X-rays, when deemed useless by hospitals, were illegally sold or stolen, cut in rounded shapes with cigarette-burn holes in the middle, then needled by a Telefunken recording lathe – a machine that records audio and sort of etches it onto the material. Lastly, they were sold on the black market (sketchy men on the streets) to anyone who had a record player and wanted to hear The Beatles. Of course, sometimes scamming occurred and false ‘records’ were sold, these being the unintentionally foundational roots of experiences on platforms like Napster in the late 90s – early 2000s.

In this case, operational images – the x-rays typically serving their purpose in the medical field – are re-operationalized into cultural artefacts, still maintaining an element of commodification.

So, what we’re seeing is a process of mutation. What was initially an idea of operative imagery being de-functionalized, is really a redelegation of purpose. It’s ‘neither created nor destroyed’, just moves to a different industry – from surveillance to advertising, or from the medical industry towards the cultural sector. The commodification of the military is not an unfamiliar concept, yet the ‘vibe-ification’ of operational images – the field of which has been synonymous with violence, brute force, authority, etc. – drags an uncomfortable feeling behind it.

On the other hand, when looking at the second example, the re-operationalization worked as an act of resistance against a culture-thwarting regime. Though some profited from it financially, it was also an opportunity for the general public to access outside culture. Long live Pink Floyd.

Kristiāna N. Pūdža has just graduated Willem de Kooning Academy with a BA in Graphic Design, with special interest in media theory and visual cultures. A crystallized form of her thesis or ‘research document’ has been made into this post.

Depressifying and Terripressing Times, or, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Los Angeles, September 6, 2025

Dear Geert —

I’ve been writing “The Present Crisis” letters not only to explain what the America looks like from the inside to those outside its borders, but also to sketch new taxonomies for US citizens to have a mental map for how to move forward. Yet, as the attacks on, well, everything accelerate exponentially, the ability to maintain critical distance diminishes. Writing this from Los Angeles, a deep blue city in a deep blue state, much of the first hundred days’ damage done by the Trump administration felt somewhat distant. So much was centered on Washington itself, and the most blistering punishments of higher education were happening to the east coast Ivy League institutions, Columbia and Harvard in particular.

As I wrote a few months ago, my vantage point was of a storm moving toward me rather than a report from inside the maelstrom. That was then, before ICE agents started raiding LA’s home store parking lots, grabbing day laborers, abducting the fruiteras who sell freshly cut melon and pineapple from pushcarts at the side of the road, and arresting students outside high schools in East LA. That was before ICE agents created clout-chasing calvary photo-ops raiding Macarthur Park on horseback, and massing to intimidate Gavin Newsom, the state’s Democratic governor, when he was giving a speech at the Japanese American National Museum in Little Tokyo (an institution built specifically to commemorate the last time the US government interned what it classified as internal enemies during World War II). And when the people of Los Angeles rose up against this vast overreach, the Trump administration sent in the National Guard and the Marines, a warning to the rest of the country—the blue parts, at least– that they were next. As I write this. Washington, DC has National Guard troops that the Trump administration imported from six red states, four of them former members of the Confederacy. Next up in this reversal-of-fortune cos-replay of the Civil War are Chicago and New York.

It’s not just cities under attack and threatened with occupation. It’s also the intellectual and economic drivers in those cities, namely the universities. This conflict has manifested in multiple ways, but the most serious and significant is the attack on science. Science, based as it is in evidence, experimentation and iteration, all in search of a facticity that can in turn be challenged and improved, serves as an alternate source of power and knowledge to authoritarian rule. This is true in Russia, it’s true in Hungary, it’s true in China. It’s why those countries’ rulers ruthlessly control their science and university faculties. Now it’s manifestly happening in the US, under a mandate that Donald Trump feels deeply, no matter that he won the 2024 election by a mere one and a half percentage of the popular vote. His mandate springs, as I’ve written earlier, from the feels. He and his MAGA followers literally rather than metaphorically feel he has a mandate from God, that it was divine will that saved him from two assassination attempts during the 2024 campaign, two impeachments in his first term, one serious bout of COVID, and an ongoing, exercise-free regime heavy on fast food burgers and Diet Cokes.

Various agendas—personal, ideological, political —intersect in the attack on science. There’s Trump’s own characterological aversion to anyone who claims to know anything more than he does (no American president has ever publicly claimed to be a “smart person” more than Trump). Add in an abiding push/pull towards elite education from someone who touts his and his family’s, and even his appointees’ Ivy league credentials while loathing the culture and traditions of those same institutions. Moving beyond the personal, there was a detailed plan developed during the 2020-2024 MAGA interregnum (aka the Biden administration) called Project 2025 that was explicit in its desire to destroy higher education as an incubator of “wokeness” and in the process “expose schools to greater market forces” (as if the neo-liberal turn the academy took decades ago hadn’t done this already). And so, we come to J.D. Vance, graduate of a top-ranked public university as well as a Yale Law school alumnus, who parlayed his version of couch-fucking populism into his lick-spittle Vice-Presidency. In a speech back in 2021, he was explicit about the politics he wanted to pursue with his boss and the radical dismantlers of Trump 2.0. He titled his speech, “The Universities are the Enemy,” and so we have been treated since inauguration day.

For three-quarters of a century, the federal government and universities worked in tandem, the government funding basic research and supplying monies for grants and loans to build American science into a dominant global behemoth. Yet this interrelationship left universities open to attack, and shamefully defenseless against an administration that simply does not care what happens to basic science, medical research, and non-commercial inquiry. As much as the Trump administration hates Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) and classes in critical race theory (CRT), there just wasn’t enough money flowing to them to hurt universities by turning down the spigot. But federal support through an array of alphabet agencies like the NSF (National Science Foundation) and the NIH (National Institutes of Health), not to mention the big D departments like DOD, DOE and DOA (the departments of Defense, Energy and Agriculture), offered a hundred billion dollar lever Archimedes would envy to punish universities for… well, anything MAGA feels like.

So it was that first they came for the Ivies about “antisemitism” (all justifications will be in quotation marks because even the Trump administration doesn’t believe in them) with funding withheld in the range of 2.2 billion for Harvard and 400 million for Columbia; then for “transwomen in sports” with 175 million at the University of Pennsylvania; and in a non-Ivy move, 800 million from John Hopkins because of “waste, fraud, and abuse” in their administration of foreign aid research and programs. The Baltimore-based university was targeted in the first days of Elon Musk’s aborted yet disastrous DOGE initiative (it’s been less than eight months, but down the memory hole goes the fact that the richest man in the world made the globe’s poorest, sickest children his first target when he and his minions in the Department of Government Efficiency went after the United States Agency for International Development).

These were the clouds I was watching gather during the first hundred days of the Trump administration. On the two hundredth day, the storm hit my institution full force, with a one billion dollar fine imposed for “antisemitism” at UCLA. For those of us on the Left Coast, and especially we who have a connection to the statewide University of California (ten campuses from Berkeley in the north to San Diego in the south), it’s been disheartening to see how little the national media has covered our extinction-level threat versus that of our private peers on the east coast. Human networks still matter a lot, apparently. The fundamental difference between settlements with a school like Columbia and Brown and the continued extortion of the UCs (“affirmative action” is the pretext for new investigations into UCLA, Berkeley and UC Irvine) is that it will be public rather than private money for the payoffs. In a blue state like ours, with a governor who has positioned himself as the most vocal political opponent of the administration, there’s no surety as we head back to campus after the quiet of summer.

These are the things I “feel” the most acutely right now, but each day brings worse and weirder news. This administration has set the stage for a global catastrophe set off by its trade economic policies; it plans to transfer one trillion dollars from the poor and middle class to the rich via Trump’s signature One Big Beautiful Bill act; and it flouts international law from the Middle East where we support ethnic cleansing, to South America where we summarily kill foreign nationals in international waters because we accuse them of “drug dealing” (which in the United States is not and never has been a capital offense, much less one administered without a trial). There are even semantic assaults, like rebranding the Department of Defense as the Department of War. The glee with which all this chaos is embraced by between one third and one half of the American electorate demands a neologism that combines terrifying and depressing, “depressifying” or “terripressing,” perhaps.

Back in the 1990s, a comedian named Paula Poundstone popularized the phrase, “this is why we can’t have nice things.” The internet picked this up and trended it as way to point out (decades before the term itself was coined by Cory Doctorow in 2022) the enshittification of stuff they liked or liked to do online. Lately though, the “this is why we can’t have nice things” phrase has taken on a distinct racial and class dimension, especially since the reckonings brought on in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd. The Movement for Black Lives, better known by its earlier acronym BLM, the public protests they helped to organize, and the associated social disorder that was contemporaneous (though nowhere near as prevalent within the mass social movement as right-wing media made it out to be), brought about a revulsion against the idea of people of color and their allies having access to public space to express their concerns, anguish, and hope. For many non-urbanites, a core MAGA constituency, the vast percentage of peaceful BLM actions were entirely outweighed by the violence that accompanied a few of them. Watching videos of isolated conflict and property crimes looped over and over again was for the Fox News-consuming elders a replay of the summers of rage inaugurated in Watts in 1965, and for overly-online rightest youth they were visible proof of the race wars prophesied on the 4- & 8- Chan boards they shit-posted to.

The ”nice things” we couldn’t have were now those consumer goods locked up in certain “urban” drugstores, a visible sign of the “American carnage” that Trump invoked in his suburban-revival-show-cum-rallies throughout the 2024 campaign. Trump has a visceral “feel” for big cities that is frozen in amber in the period that he first emerged as a public figure. To hear him prattle on about the chaotic dystopia of America’s metropoles is like sitting in a Times Square movie theater in 1980 watching previews for exploitation flicks like Death Wish, Maniac, and C.H.U.D. (the last of which stood for the Cannibalistic Human Underground Dwellers who lived with the also mythical albino alligators in the sewers beneath New York’s streets).

In other words, for Trump, New York will forever be a city in which he rides in a Lincoln Town car through filth-strewn streets next to a cab driven by Travis Bickle, that most deranged Gothamite portrayed by Robert de Niro and put to celluloid by Martin Scorsese in Taxi Driver. Trump’s cities are never the places that urbanist Jane Jacobs discusses where the wondrous and the strange are forever in conversation, gifts that “by its nature the metropolis provides [that] otherwise could be given only by traveling.” No, America’s cities are “lawless” “hellholes” where “bloodthirsty criminals” and “animals,” many of them “illegals,” create “killing fields.” In mid-August he ran down a list: “You look at Chicago, how bad it is. You look at Los Angeles, how bad it is. We have other cities that are very bad. New York has a problem. And then you have, of course, Baltimore and Oakland. We don’t even mention that anymore.” Not noted but always dog-whistled was that the mayors of every one of these cities is Black.

Getting back to white people, Trump tells us that even his “friends” in Beverly Hills have to leave their automobiles unlocked because they are terrified that criminals will shatter the windshields to steal their car stereos. That stereo comment is the tell, because with con men there’s always a tell. Car stereos were discrete pieces of equipment in the 70s and 80s and were easy to steal and sell. In 2025, sound systems are fully integrated into luxury vehicles, and what other kinds of cars would his friends in Beverly Hill have?

This pseudo-apocalypse is yet another obsession of Trump’s that harkens back to the NYC subway systems of his youth, even if he never rode them. The president of the United States is trapped in a ‘70s and ‘80s fantasyland of white retribution against Black and brown people. If Donald Trump has a soul—a proposition that even he seems uncertain of—part of it belongs to a man named Bernie Goetz, another outer-borough white guy who achieved his own measure of fame, or infamy, for imposing his will on urban space.

Bernard Goetz, was born in Queens to a German-American father a year after Donald Trump was born in Queens to a German-American father. Bernie was no nepo baby, though, putting himself through NYU’s engineering program and then founding a small electronics business that he ran out of his apartment. In 1981, after being mugged for the second time, Goetz purchased a handgun that he carried on the streets and in the subway, even though he had been denied a city permit that would have allowed him to do so legally. In 1984, he was on the #2 subway line that runs between Brooklyn, Manhattan and the Bronx. Goetz was approached by four young Black men from the Bronx, one of whom said he wanted five dollars from the seated Manhattanite. At that, Goetz shot all four, three of whom were carrying screwdrivers. He shot one of them, Darrell Cabey, a second time, after saying, “You seem to be all right, here’s another.” The second bullet went through Cabey’s spine, severing it and leaving him a paraplegic. Goetz exited the train and fled to another state, returning a week later to turn himself in. At that point, and throughout the criminal and civil trials that followed, he claimed the shootings were in self-defense. The New York Daily News set up a tip line after the shooting to get information, but the paper’s staff was astonished that most of the calls offered support and sympathy for Goetze. The paper wrote: “It did not seem to matter to the callers that the blond man with the nickel-plated .38 had left one of his four victims with no feeling below the waist, no control over his bladder and bowels, no hope of ever walking again… To them the gunman was not a criminal but the living fulfillment of a fantasy.”

It took decades, but Donald Trump has bested his fellow blond Queens doppelganger, and the fantasy of old men’s revenge is more powerful now that they are both approaching eighty years of age than it was back when they were young. We’ve seen these fantasies of physically powerful old men pop up all over American culture in the past decade, a sign of an aging population that refuses to give up control. It’s not just an entrenched gerontocracy, it’s one that fools via — and is in turn fooled itself by — an imaginary. How does this imaginary manifest in the world? In the AI slop-driven MAGA memes of Donald Trump as a ripped Rambo flexing astride a tank, or an NFT of “SuperTrump” with 8-pack abs and a cape. All this based on a man who believes that the human body is akin to a battery, with a finite amount of energy, which exercise only depletes.

Yet this waddling golfer and his meme troops are only following Hollywood, which finds it harder to fashion new action stars than to retread aging ones, at times to the point of hilarity. Nicholas Cage, in a seemingly never-ending attempt to pay down back tax bills, makes movie after movie in which he beats up younger and stronger opponents for two straight hours. See The Old Way (2023), The Surfer (2024), and most delirious of all, and with the least believable tile, The Retirement Plan (2024). Yet in his early sixties, Cage is a veritable tyro in comparison to septuagenarian Liam Neeson, who parlayed the revenge fantasies of the Taken franchise (2008 to infinity) into frozen landscapes in Cold Pursuit (2019) and The Ice Road (2021) and Ice Road: Vengeance (2025)); on planes in Non-Stop (2014) and trains in Commuter (2018); and even into the dementia clinic, with the far more believable premise of an aging assassin in Memory (2022). At least Cage and Neeson have an air of humor and a sort of working man’s shrug to their performances: of course they will take a paycheck for pretending to outfight jacked opponents decades their junior in hand-to-hand combat. It’s not called acting for nothing. Denzel Washington is yet another seventy-year old, Oscar-winning actor who has yet to meet a Russian gangster (the Equalizer franchise, 2014-also apparently to infinity) or ex-con rapper (in Spike Lee’s insufferable Highest 2 Lowest, a 2025 remake of Kurasawa’s sublime 1963 film, High and Low) who can slow him down even a step.

Trump feels popular impulses more than he understands them, but regardless he’ll act on either. So it is that while to most of the entertainment industry it seemed odd at best and out-of-touch to demented at worst when Trump wanted “Special Envoys to me for the purpose of bringing Hollywood, which has lost much business over the last four years to Foreign Countries, BACK—BIGGER, BETTER, AND STRONGER THAN EVER BEFORE!” he appointed actors Jon Voight (aged eighty-six) Mel Gibson (sixty-nine) and Syvester Stallone (seventy-nine) to be his “Hollywood Ambassadors.” All three were vocal Trump supporters in 2024, all three still play action roles, with Stallone having a literal franchise of aging beefcake in The Expendables (four films so far). Trump has already selected Stallone—who called Trump our “second George Washington” during a visit to Mar-a-Lago—for Kennedy Center Honors, another sign of the President’s ‘80s pop culture fixation. More salient here is that the three actors have a combined age of two hundred and thirty four.

Yet even in MAGA world, facts assert themselves. In 2024, just days after Trump won both the electoral college and the popular vote, the old guys of America who had voted for him picked yet another champion in their fight against youth, in a match-up between icons representing two generations of Trump supporters.

In this corner, the 58-year-old, one-time heavyweight champion of the world, a true student of the art even if he did bite off Evander Hollyfield’s ear, a long-time friend of the President, who’d defended him against the rape charges that sent the former champ to prison. Ladies and gentlemen, “Iron” Mike Tyson.

And in this corner, a 27-year old top Youtuber-turned fighter who understood that the exhausted sport of boxing, on the ropes itself against mixed martial arts (MMA for short), could be taken over by someone who knew more about monetizing eyeballs than what combinations Primo Carnero threw against Max Baer in 1934. Ladies and gentlemen, Jake “El Gallo” Paul.

When Netflix featured the Tyson/ Paul fight, it attracted the largest audience in the history of streamed sports. The fans were firmly in the OG’s corner, laying almost seventy percent of the bets on Tyson. I have to think that lots of those punters gambling with such abandon were the very same audience of the aforementioned aging action stars, but this time looking to see the payback for real. Yet the sportsbooks had Paul as the strong favorite, at -205 (meaning you’d have to bet that amount of dollars to get a hundred more back in winnings). Perhaps it had something to do with the thirty-one year youth advantage Paul had over Tyson, who hadn’t fought in two decades. Yet, in the end, the old man did not triumph, his retirement plan did not include victory, and Tyson was shown to be an expendable part of Paul’s rise.

Right now, it sometimes seems like the best we can hope for is the return of the real. That a gimmicky fight like this resulted in the continued upward trajectory of a figure as obnoxious as Jake Paul (El Gallo – the rooster, seriously?) is lamentable but at least it follows the laws of physics and precepts of medical science. It was stupid, but at least the outcome was honest. It wasn’t a nice thing, but in this crisis period, it was a thing we could have. Heaven help us.

Capitalism, Semiotics, and the Subjectivities of the End: Interview with Alessandro Sbordoni

By Leonardo Foletto and Rafael Bresciani for BaixaCultura

In July 2025, the Italian-born, London-based Alessandro Sbordoni was in Brazil for the launch of Semiótica do Fim: Capitalismo e Apocalipse (first version published as INC Network Notions #1: Semiotics of the End: On Capitalism and the Apocalypse), published by SobInfluencia. The book, as we’ve already commented in our presentation text, is a collection of thirteen essays that investigate how the end of the world has become just another sign of semio-capitalism. The thesis – if we can call it that in a text so open to provocations and different readings – is that the end of the world is “just another sign” of semio-capitalism: the apocalypse, as traditionally conceived, will not occur because it is already in permanent course. There is no longer any difference between the end of the world and capitalism itself: both reproduce incessantly according to the semiotic logic of capital, says Sbordoni. His book, then, presents itself as a manifesto that invites us to think about what “end” means today.

On July 17, 2025, one day before the book’s first launch at the head office of SobInfluencia publishing house in downtown São Paulo, we spoke with Alessandro in an Amazonian restaurant inside the gallery. For BaixaCultura, Leonardo Foletto and Rafael Bresciani, with participation from Rodrigo Côrrea, editor and designer at SobInfluencia. Between Cupuaçú amigo (the local version of the “Caju Amigo” drink) and Tacacás (the famous Amazonian “soup” with jambu and tucupi), the conversation ranged from Semiotics of the End to the relationship between high and low culture, anti-hauntology, digital magazines as spaces for intellectual encounter, underground culture, technology, and contemporary theory. Below is an edited transcript of the conversation.

BaixaCultura: To begin with: how did the idea for the book come about? In what context was it produced? And tell us a bit more about your writing journey.

Alessandro: Around 2020, I read And: Phenomenology of the End by Franco “Bifo” Berardi. Reading it, I found the approach to capital and capitalism very intriguing, something that stayed in my head for a while. I had just written another book about something completely different, but I knew I wanted to do something like that. A few months later, I wrote an essay, which is the first in the book, with a different subtitle, but the main title was “Semiotics of the End.” I didn’t know what would come of it; it was about boredom and the end of the world. I published it on Blue Labyrinths and, a few months later, I published another essay, again with the same title and a different subtitle; then the third essay followed, and so on. Thus, everything started coming together. Obviously, the title “Semiotics of the End” is a reference to “Phenomenology of the End”, and I thought I would do something similar.

The book developed organically. Little by little, I started realizing that I wanted to mix the idea of semio-capitalism as a way to analyze, criticize, and go beyond the idea of capitalist realism in Mark Fisher, which is the core of the book.

Leonardo: Are you a philosopher?

Alessandro: There’s a quote by Guy Debord, who says: “I’m not a philosopher, I’m a strategist.” I’m not a philosopher; maybe, I’m a strategist or I would consider mysel as a theorist, at least. Philosophy carries all this Western cultural baggage with which I do not want to identify myself. I would rather see myself as a theorist, which also brings with it certain problems, such as: I’m not searching for the truth in what I write. I see it more as a political or cultural endeavor, if you prefer, but never searching for truth or knowledge. All that stuff is nonsense…

BaixaCultura: I’d like to ask about Blue Labyrinths and Charta Sporca, two digital magazines that you are engaged in.

Alessandro: I started publishing the first excerpts of the book Semiotics of the End, which were then gathered with other essays inside the book. With Blue Labyrinths, it all started when I read the anti-hauntology essays by the magazine’s founder, Matt Bleumink, which I wanted to expand and, eventually, formed the last chapter of the book. After publishing a few essays on Blue Labyrinths, Matt and I became good friends, and then, little by little, I started playing a role on the editorial board of Blue Labyrinths together with another person.

That’s the story of Blue Labyrinths. For Charta Sporca, I really wanted to publish and do something with them. I first discovered them when I was still in Italy, and I always appreciated the mix of politics, literature, and philosophy, all together.

BaixaCultura: In Blue Labyrinths: what kind of contributions are you looking for? And how does the magazine position itself within the current landscape of cultural and philosophical publications?

Alessandro: It’s quite simple. We accept any submission that we deem interesting for us. If you read the description, it says something very general: “An online magazine focusing on philosophy, culture, and a collection of interesting ideas.” And those two words, “interesting ideas,” are the main part because all magazines and publishers tend to admit that they focus on one thing, maybe because it’s easier or because people have limited understanding. We often publish things that stretch a bit, and we even published some things that we tend to disagree with to a certain extent, even on a political level. Nothing too crazy, of course – I would never publish a fascist piece, that’s for sure. But there have been disagreements, and that’s interesting. For example, it’s been a very good policy because we’ve attracted all those writers who don’t know where else to publish, because all the other magazines are very specific, and if you don’t fit, screw it. So, it was very interesting. And it wasn’t my concept; it was Matt, the founder, who always had this mindset, and I always liked that. I think I was attracted to it because also in my writing I do this: I try to bring in many different things altogether at the same time.

BaixaCultura: And so, why magazines? What do you like about digital magazines?

Alessandro: I personally see them as a kind of cultural gym (in the etymological sense of the term). It’s almost like a testing ground or, if you want, a training in the military sense. It’s like a training for a theory to then really do something important. But no, I just see it as something contingent. Publishers are also contingent. In an ideal world, you would just come together. It’s always a compromise.

BaixaCultura: About Charta Sporca, to me, it appears to engage with contemporary Italian theory and culture, including your own work and figures like Mark Fisher and Deleuze. How does editing this magazine inform your own theoretical development? And what role do you see intellectual and digital magazines playing today, especially in your case? Italian intellectual history has a huge history of magazines, with Quaderni Rossi, Classe Operaia, and A/Traverso, for example, in the 1960s and 1970s.

Alessandro: For me, the answer is straightforward. Imagine the magazine was a space with which you interact. You go there often and you see what people are doing. And what comes out of it is not just a theory or an idea. Yes, you read interesting pieces, and they may spark something – but that’s never the main and most important thing. The most important thing is that you get to meet the people and you create relationships, as we are doing right now. This is something crucial that I’ve realized in the past few years: the most interesting thing about writing is not writing, it’s getting to meet the people. It’s being part of a “community,” for lack of a better word – even though I never liked the word “community” because it almost demands to be defined. They are encounters. Encounters with the people that you meet do inform your theory, but it’s also contingent, in a sense. Theory is secondary to the reality of meeting someone. So, these magazines are a potentiality for new encounters.

BaixaCultura: And why magazine sites and not, for example, social networks?

Alessandro: Well, because there is a certain autonomy in the magazine. This goes back to what I was saying about those “interesting ideas.” You just welcome everyone in. I’m just happy to meet anyone who has something interesting to say, especially if they disagree. It’s okay.

BaixaCultura: Going back to the book. I read here that your book opens with the provocative statement that “the end of the world is just another sign of semio-capitalism.” Can you explain what led you to this conclusion and how you develop the concept of semio-capitalism as distinct from traditions of capital critique, like in Bifo’s books, for example? If there are differences or not.

Alessandro: There are differences, definitely. I always take all these ideas as starting points. In this sense, I’m not trying to develop the concept of semio-capitalism, but I find it an interesting ground. What happened was that, at some point, the difference between materiality and immateriality, between a culture based on production and actual commodities – the dichotomy between production and reproduction, in the terms I put it – has been abolished. The world has become more ephemeral and immaterial: it’s just a structure of signs. The interesting thing is that capitalism has been able to link itself to the reproduction of signs and reproduce itself through signs, regardless of what the signs mean. This could have been a problem in the past. For example, capitalism entering a radical discourse and making a profit out of it, this could have been a contradiction in the Marxist sense. I think now the discourse has been flattened, since anything can be turned into capital; anything can be a way to reproduce capital. The most extreme form of this is that the end of the world, which would be, logically speaking, the end of capitalism, is just its continuation. Because capitalism feeds off the reproduction even of its own end. Which I thought was an interesting starting point because of the intrinsic irony. I don’t think there is any contradiction, but there is a strong irony and a strong feeling that it should be the starting point for something. And I’m trying to find a way to open up to this new beginning, but I think we have to really think outside the box, because everything that is inside the box is capital.

BaixaCultura: You state that the apocalypse, as such, will not occur because it has already finished. This seems to challenge both religious and secular narratives of ending. How do you situate this claim in relation to the ecological and social crises we are experiencing? And how can we think about other relations with the ending, but how to begin?

Alessandro: There is, again, a sad joke about the climate catastrophe and the endless end of capitalism. As the catastrophe goes on, it reproduces more and more capital, and because it reproduces more and more capital, it will go on faster and faster. And, paradoxically, the few images that we now have, for example, the wildfires happening across the world, are going to increase because capital is going to increase, and capital is these images. Therefore, as capital increases, the end of the world approaches. I don’t see, following this line of reasoning, an end to capital. But as we start relating to culture in a different way and begin to see that these images are nothing but capital, that reproduction is the problem of what they represent, that will be an old way of thinking. The problem is that, if the end of the world is approaching, we are still producing content and we are still producing in a capitalist way. So, on the one hand, a solution could be to find new ways of production, but we’ve entered a new paradigm, which I dub re-production. Many of the different modes of production-reproduction have been neutralized.

So, the only thing that is left to do is to rethink where we are right now. And this is something that Geert Lovink refers to in Extinction Internet: we have to look into the abyss in order to overcome it. It’s also about looking into how this makes us feel. Paradoxically, I talk about this in terms of boredom rather than anxiety, because we are sick and tired of it. It’s been fifty or sixty years of apocalyptic predictions that didn’t come into being, because capital, as I said before, keeps reproducing itself. But if you start from here, and we in a way reshape, repurpose the concept of end and beginning in a metaphysical way – and this is why we’re also talking about philosophy. So, if we rethink what it means to be at the end of the world, as well as what it means that the end and the beginning always coexist. Once we understand this, then this opens up new ways and, in a simple word, a new imaginary.

BaixaCultura: I did a reflection, following this idea of end and beginning. We usually think about human progress as landmarks of success. When things happen positively, we landmark them. And one of these examples is when, on a personal level, we introduce ourselves as professionals, we use a Curriculum Vitae, which means the things we’ve done in life, the good landmarks of our lives. But I once heard a psychologist, who was a trauma psychologist, and who advocated the idea of a Curriculum Mortis, which is the idea that, when we acknowledge the landmarks of failure, we are able to overcome those failures. So, is this view something we can rely on in this Anthropocene, late capitalism moment? Using a Curriculum Mortis of human history as a way to approach this moment.

Alessandro: I see. There was an interesting article recently published in an Italian magazine by an author named Christian Damato, who talks about the fact that failure has been reintegrated into the discourse of success within a corporate ideology. And I think it’s a very bleak statement, yet I believe that merely inverting the problem doesn’t solve it, because in my way of thinking, it’s a question of structures. Just reverting the structure is not creating a new structure, but it may be a means to a new structure. So, even emphasizing failure could potentially be a way to something, but it’s not enough.