Welcome to Limn’s new website. Please explore while we update everything and work out some kinks… grand opening announcements to come!

The post Website under construction appeared first on Limn.

Radical Open Access Collective

Building Horizontal Alliances

Welcome to Limn’s new website. Please explore while we update everything and work out some kinks… grand opening announcements to come!

The post Website under construction appeared first on Limn.

Welcome to Limn’s new website. Please explore while we update everything and work out some kinks… grand opening announcements to come!

De Hogeschool van Amsterdam (HvA) is voor FDMCI, het lectoraat Netwerkcultuur (Institute of Network Cultures), onderdeel van het Kenniscentrum (CREATE-IT), per 1 juni 2018 op zoek naar

De Faculteit Digitale Media en Creatieve Industrie (FDMCI) is onderdeel van de Hogeschool van Amsterdam en telt ruim 6.600 studenten en 425 medewerkers. De faculteit, met een sterke crossmediale, mode en ICT-focus, is ambitieus en wil op alle fronten kwaliteit uitdragen.

Als onderzoeksmedewerker werk je samen met de lector en onderzoekers aan de opzet, uitvoering en administratie van verschillende projecten van het lectoraat. De lopende projecten van het lectoraat hebben te maken met alternatieve verdienmodellen, digitaal uitgeven en kunstkritiek. Je ontwikkelt en produceert bijeenkomsten, workshops en andere activiteiten rondom het onderzoek. Je werkt ook mee aan het realiseren van de publicaties van het lectoraat, zowel online als op papier. Een belangrijk deel van je werk bestaat uit het contact leggen met en onderhouden van netwerken van onderzoekers, kunstenaars, activisten, programmeurs, en docenten en studenten. Daarnaast denk je mee over nieuw op te zetten projecten en werk je aan de uitwerking daarvan in projectplannen, fondsaanvragen en begrotingen.

Naast de coördinerende en inhoudelijke taken draagt de onderzoeksmedewerker zorg voor een goede communicatieve en administratieve begeleiding van de projecten. Je verzorgt de communicatie rondom activiteiten van het lectoraat, zoals het schrijven van persberichten en nieuwsbrieven, het onderhouden van social media en het up-to-date houden van het blog van het lectoraat. Daarnaast onderhoud je contacten met interne en externe relaties. Ten slotte zorg je voor een goede documentatie van de activiteiten en de resultaten van de projecten, ten behoeve van kennisopbouw en -verspreiding.

Een veelzijdige collega met belangstelling voor de culturele, maatschappelijke en academische ontwikkelingen in de nieuwe media en netwerkcultuur. Je bent organisatorisch sterk en hebt ervaring met de productie van bijvoorbeeld (internationale) symposia, tentoonstellingen, workshops of andere publieksprogramma’s. Bij voorkeur heb je ervaring met het schrijven van projectvoorstellen en subsidieaanvragen. Je houdt van netwerken en staat graag in contact met verschillende soorten mensen op allerlei niveaus. Je kunt overweg met verschillende communicatiemethoden zoals bloggen, sociale media, nieuwsbrieven en het benaderen van de pers. Je bent flexibel, proactief, enthousiast en ondernemend en werkt goed samen in een klein team. Je beheerst Nederlands en Engels op hoog niveau en beschikt over minimaal bachelor werk- en denkniveau. Ten slotte heb je affiniteit met een complexe onderwijs- en onderzoeksomgeving zoals de Hogeschool van Amsterdam.

Het Instituut voor Netwerkcultuur (INC) maakt onderdeel uit van het Kenniscentrum Create-IT. Tot de werkzaamheden van het lectoraat behoren onderzoek, het organiseren van theoretisch onderwijs en het ontwikkelen en uitvoeren van een programma van seminars, conferenties, evenementen en publicaties ten behoeve van kennisontwikkeling en kennisoverdracht. Het lectoraat bestaat uit een team van vijf medewerkers. Daarnaast werkt het lectoraat regelmatig met (internationale) stagiair(e)s en gastonderzoekers.

Create-IT Applied Research is het kenniscentrum van de faculteit. Studenten en onderzoekers werken samen in uitdagende projecten op het gebied van media, mode en IT. Het centrum wordt gekenmerkt door een ondernemende instelling en multidisciplinaire aanpak. Het onderzoek vindt zoveel mogelijk plaats binnen de bedrijven en instellingen waarmee samengewerkt wordt, maar er zijn ook verschillende labs, waar nieuwe technologieën onderzocht worden en waar studenten (afstudeer)opdrachten uitvoeren.

Het betreft in eerste instantie een dienstverband voor een jaar. De werkzaamheden maken deel uit van de organieke functie Onderwijs- en onderzoeksmedewerker 2. De bij deze functie behorende loonschaal is 9 (cao hbo). Het salaris bedraagt maximaal € 3635,- bruto per maand bij een volledige aanstelling en is afhankelijk van opleiding en ervaring. De HvA kent een uitgebreid pakket aan secundaire arbeidsvoorwaarden, waaronder een ruime vakantieregeling en een 13e maand.

Nadere informatie per e-mail aan Miriam Rasch: vacatures@hva.nl (niet gebruiken om te solliciteren).

Kijk voor meer informatie over het lectoraat op http://networkcultures.org en over CreateIT op: http://www.hva.nl/create-it

Klik hier om online te solliciteren. Sollicitaties die rechtstreeks naar de contactpersoon of op een andere wijze worden verstuurd, worden niet verwerkt.

Bij de werving en selectie ter invulling van deze vacature, houden wij de HvA Sollicitatiecode aan.

Acquisitie naar aanleiding van deze advertentie wordt niet op prijs gesteld.

A sound art multimedia piece by Anthony William Rasmussen

Funded by the UC MEXUS Dissertation Research Grant

Map graphics by Julie K. Wesp

Additional Footage by Oswaldo Mejía

The megalopolis of Mexico City is experienced by many who live there as a network of “known” places, laden with both personal memory and collective meaning. Sounds provide inhabitants with a powerful means of navigation: the unique calls of street vendors, song fragments, speech, and protest chants echolocate the listener within a vast spatiotemporal grid. The title of this piece (“the snail/the shell”) refers to the prolific spiral motif in Mesoamerican cosmology and alludes to a nonlinear vision of time and space.

El Caracol, Sounding Board Installation, 2015, Image by Leo Cardoso

The piece consists of four journeys, each beginning at the outskirts of the city and ending in or near the Zócalo—Mexico City’s central plaza and the symbolic heart of the nation. The video element consists of footage captured while walking through various sites in Mexico City and represents the phenomenological present. The audio element provides a counterpoint to the visual: sounds meander and drift from the visual field; occasional ruptures of historical sound expose layers of this audible palimpsest.

Sounding Out! is thrilled to host a virtual installation of “El Caracol” right here, right now:

—

Featured Image: Screen Capture from El Caracol

—

Anthony W. Rasmussen is a musician, educator, and postdoctoral fellow at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Currently, he is investigating the transformation of whistles from a rural system of long-distance communication to an aesthetic/symbolic practice in Mexico City. In 2017, he completed a PhD in ethnomusicology from UC Riverside with a dissertation on sound culture and urban conflict, “Resistance Resounds: Hearing Power in Mexico City.” His work can be found in Ethnomusicology Forum. Anthony also holds an MFA from UC Irvine where he studied Persian classical music, music composition, and interactive arts technology. He has composed for film, a range of traditional and experimental ensembles, and is singer/songwriter for the pop group, The Fantastic Toes.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

Standing Up, For Jose–Installation Piece by Mandie O’Connell

SO! Amplifies: Sounding Board Curated by Leonardo Cardoso–-Jay Loomis

SO! Podcast EPISODE 24: The Raitt Street Chronicles: A Survivor’s History–Sharon Sekhon

Voices at Work: Listening to and for Elsewhere at Public Gatherings in Toronto, Canada (at So-called 150)–Gabriela Jimenez

detritus 1 & 2 and V.F(i)n_1&2 : The Sounds and Images of Postnational Violence in Mexico–Luz María Sánchez

Download and Donate.

The post Download and Donate appeared first on Limn.

You can now download PDF versions of Limn… and you can donate too!

Limn’s new website is totally better than the old one… check it out!

The post Welcome to the new Limn! appeared first on Limn.

Limn’s new website is totally better than the old one… check it out!

We are pleased to announce the publication of On Editorialization: Structuring Space and Authority in the Digital Age by Marcello Vitali-Rosati. The 26th edition in the Theory on Demand series can be freely downloaded as pdf or epub here.

We are pleased to announce the publication of On Editorialization: Structuring Space and Authority in the Digital Age by Marcello Vitali-Rosati. The 26th edition in the Theory on Demand series can be freely downloaded as pdf or epub here.

In On Editorialization: Structuring Space and Authority in the Digital Age Marcello Vitali-Rosati examines how authority changes in the digital era. Authority seems to have vanished in the age of the web, since the spatial relationships that authority depends on are thought to have levelled out: there are no limits or boundaries, no hierarchies or organized structures anymore. Vitali-Rosati claims the opposite to be the case: digital space is well-structured and material and has specific forms of authority. Editorialization is one key process that organizes this space and thus brings into being digital authority. Investigating this process of editorialization, Vitali-Rosati reveals how politics can be reconceived in the digital age.

This is something you just don’t hear about in the history books.

–Alex Hutchinson, Creative Director, Assassin’s Creed III

What does it mean to speak American? According to Laura Amico, a teacher in the Cliffside Park school district in New Jersey, to speak American is the opposite of speaking Spanish. As suggested by this video, captured by students via Snapchat before they walked out in protest, to be American is the same as to speak American. Evidently, to speak American is to speak English, a historical curiosity, given that English was not spoken on the North American continent until the 17th century, preceded by many Native American languages and, ironically, Spanish. In simplest terms, “American English” is not a homogenous dialect either. What kind of “American English” does Laura Amico exalt as acceptable for patriotic conduct? How does an American patriot speak?

Colonel Tarleton, painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1782, British National Gallery, CC license

In The Patriot (2000), Mel Gibson plays Benjamin Martin, a hero of the French and Indian War, who is forced out of his South Carolina plantation-managing life to avenge the deaths of his sons at the hands of the British during the American Revolution. The main British villain of that film, the fictional Colonel Tavington,–played in sneering style by Jason Isaacs—is notable for his barbaric conduct (among other things, he traps civilians in a barn and burns them alive). British audiences were noticeably aghast at this characterization, which implicitly compared British command of the time period to Nazi atrocities in World War II. Tavington may in part have been based on Banastre Tarleton, a notorious and brutal, misogynist dragoon whose victory at Monck’s Corner was among the bloodiest battles in the dirty war fought in the south at the end of the Revolution, or Lord Rawdon, a serial rapist and generally unpleasant English officer.

Nevertheless, Tavington’s barn-burning exploits are more likely based on American General John Sullivan’s slash-and-burn campaign against British-allied Mohawks, Senecas, Onondagas, and Cayugas, a subject little discussed in American history. This culminated in a 1782 massacre at Gnadenhutten in Ohio, where white Americans murdered 96 Delawares who had converted to the Moravian faith (pacifists). Evidently, in The Patriot, the conflict was not a civil war, and character was constructed in part through dialect (as detailed below, dialect here refers to all the clues in the way a person speaks, not just his or her accent).

Although Tavington’s conduct in The Patriot manifested visibly onscreen, his dialect said much about him. As noted in a recent Atlantic Monthly article, entertainment—such as Disney cartoons—can “take [bias] and pour concrete over it.” Rosina Lippi-Green, a linguist, notes that such biases are then difficult to remove: “They etch it in.” Another linguist, Chi Luu, suggests that with English RP (see below), the effect is more subtle; such accents go beyond “pure evil” by shading villains as more educated and intelligent—but still bad. Relating these findings to The Patriot, viewers understand Tavington as educated, intelligent, and evil through his English RP dialect; moreover, in black-and-white terms, his dialect makes tangible that he is completely different from the rough-and-ready, courageous Benjamin Martin. An aural line is drawn between American “good guys” and British “bad guys.” The British are fighting just to be sadistic or greedy; the Americans are fighting to defend their way of life.

Compared to media about other American conflicts, there has been little recent dramatic depiction of the American Revolution. Historically, one reason dramatizations of the American Revolution have historically remained rare is the tradition of American reverence for the “Founding Fathers,” causing their depiction as human beings to be circumscribed. Just as visual conventions have been built up regarding the antagonists of the conflict, so, too, have aural conventions in audio-visual representations such as a general use of a Standard North American accent for American (patriot) characters (whether they hail from northern or southern colonies) and English RP for all (villainous) British characters. The effect of this is epitomized by the example from The Patriot above: “good guys” versus “bad guys.”

While the way characters sound is important in most creative works—from the written dialect of Dickens’s characters to the chilling, mask-assisted tones of Darth Vader—it is no more so than in audio drama. Richard J. Hand and Mary Traynor have argued in the The Radio Drama Handbook (2011) that the elements of audio drama are words, music, sound, and silence. Arguably the most important of these to the audio drama are words. Alan Beck’s work on radio acting further argues that to create character through words and sound, refinement of dialect is needed. In this context, dialect refers to more than just a regional pronunciation: it includes details on a character’s geographical region, social class, gender, age, style, and subgroup.

In terms of The Patriot, probably the highest profile pop cultural depiction of the American Revolution until Hamilton, accents mattered. “A well-educated British accent,” in American films at least, “had come to serve as a sufficient shorthand for villainy” as Glancy pointed out, or “British, upper class, and a psychopath, happily burning people alive,” as a 2010 Daily Mail article put it. Whatever his villainy, would a historical Colonel Tavington, have sounded the way he did as depicted in The Patriot? How did those on the North American continent in the 18th century sound?

Richard Cullen Rath has convincingly argued that sound was incredibly important in colonial America, but what role did speech in English have? David Crystal, in discussing the Globe Theatre’s 2004 production of Romeo and Juliet in original pronunciation (OP)/Early Modern English (EME), was most frequently asked one question: how do we know? How do we know what Shakespeare’s English sounded like? For EME, spelling, contemporary accounts of the language, and the use of rhythms, rhymes, and puns illuminate this area. Crystal noted that EME would not sound like any modern accent but would have the pronunciation of “rs” in common with “rural” accents, as in Ireland and the West Country (Somerset).

This is important because the association of Shakespeare with a certain kind of English accent—the RP referred to below—has long had the effect of making his works less accessible than they might have been. If Shakespeare’s actual working dialect had more in common with “rural” accents like Irish and West Country, the latter of which is often still designated as a shorthand for stupidity in common with American southern dialect, this has a liberating effect on Shakespeare in performance. It may sound “strange” at first, but it suggests that Shakespeare can/should be performed in a vernacular, at the very least to make it more accessible to a wide variety of audiences.

Crystal has suggested that, “It is unfortunately all too common to hear accents on stage or film in which—notwithstanding the best efforts of dialect coaches—accuracy and consistency throughout the performance leaves, shall we say, a little to be desired.” Sky 1’s recent big-budget effort in historical drama, Jamestown, set in 1619, is diverse and rich in dialect, with characters speaking with Irish, northern English, southern English, and Scottish accents—nor are they uniform in suggesting that one accent will signify the character’s goodness or badness (though it has to be said most of the southern English-speaking characters are, at the very least, antagonistic). Most of the Native American characters have so far not spoken English rather than racist “Tonto talk,” and white English-speaking characters must speak Powhatan (or use sign language) in order to communicate. As actor Jay Tavare points out, early Hollywood was not concerned with the accurate portrayal of indigenous languages, given that Navajo extras were most often used in Westerns (meaning the Diné language of the southwest was heard regardless of where the film was set). More recently, even such films as Dances with Wolves (1991), which has generally received praise for its accurate portrayal of Sioux/Lakota culture, included Lakota dialogue which was linguistically imprecise. Clearly, there is still a long way to go.

Suppose we decide we cannot ever know how such historical actors sounded, so we decide to depict 18th century English speakers based on other criteria. How do directors, actors, and voice coaches bring the viewer/listener as close to the author’s intent as possible in fictional depictions of the years surrounding the American Revolution? How is the 18th century made accessible through dialect? As Glancy suggests above, British officers in film, television, and radio depictions of the American Revolution are most commonly associated with Received Pronunciation (RP), though the term was not coined until 1869, and, as Crystal points out, the “best speech” heard in the English court of the 16th century was “nothing like” RP. In fact, it was probably influenced by the Devonshire accents of Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh (an English so far in Jamestown associated with servants . . .). As Edda Sharp and Jan Haydn Rowles point out in How to Do Standard English Accents, RP has almost disappeared in England, “now confined to a very small section of society, the older upper and upper middle classes, older actors and broadcasters.”

The officer class of the British Army in the 18th century was in fact largely composed of Scots (as per Stuart Reid and Paul Chappell)—though how much they retained their Scottish identity (including accent) is of course impossible to know. As Kevin Phillips in 1775: A Good Year for a Revolution points out, within England, support for the colonies during the American Revolution was generally strongest in the major cities and in the eastern and southern counties—the same places where during the Civil War, support had been strongest for Parliament and Cromwell. Support in Scotland was limited to a small fringe. By contrast, statistics from Revolutionary America 1763 to 1800: Almanacs of American Life on the ancestral origins of the white population of Virginia in 1790 make Scotch-Irish (11.7%) and Scottish (5.9%), the second-largest groups after English. References to the Scottish officer class are made in Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, where Colonel Munro is referred to as “the Scotsman” (played memorably in the Michael Mann film by Maurice Roëves). Beal suggests that guides to “correct” pronunciation in the 18th century were often written by and for Scots—to pass as “British.” The Scottish people have had a long history of wishing to disassociate themselves from rule by the English (as evident in the 2014 Scottish Referendum). The Wars of Scottish Independence in the 13th and 14th centuries were fought between English and Scottish forces, at the conclusion of which Scotland retained its status as an independent state. However, in 1707, the Act of Union unified England and Scotland under one government.

With these many regional British accents potentially to be heard in the British Army in America in the 18th century, and with approximately 92.2% of white colonists in Virginia hailing from the British Isles in 1790 (including England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales), it is perhaps curious that there has been so little variation in dialect in media depictions such as films, TV, and radio. Traditionally, for example, George Washington has been depicted with a Standard North American accent and not a modern southern American accent. This is also true in the case of Colonial Williamsburg re-enactors.

Besides being generally a very sound depiction of the Revolutionary period, HBO’s John Adams (2008), based on David McCullough’s book, is also unusual as far as accents go. John Adams gives the British King George III, played by Tom Hollander, Standard Neutral English, but it does something very unusual with its American characters. Virginian characters (including Washington and Jefferson) have suspiciously Somerset-sounding accents. John Adams introduces a clear regionalism in Anglo-American accents that goes beyond the singling out of the Boston accent (which is generally personified in John Adams himself). It isn’t clear why this decision is made; the accent does not belong exclusively to Virginian characters, as it is also the accent of Benjamin Franklin, proudly Pennsylvanian, and Alexander Hamilton himself. Is the shorthand present to aurally distinguish between Loyalists, and American rebels? What affinity, one might ask, does the Somerset accent have with a depiction of the American character?

Standard North American speech is rhotic (people who say an ‘R’ whenever it is written), as is the Somerset accent (and, as Ben Zimmer explains, was associated with country speech in England from the 17th century). This contrasts with Neutral Standard English Accent, which is non-rhotic (people who only say an ‘R’ if there is a vowel sound spoken after it). Perhaps the filmmakers had in mind the best guesses about how “proper” Anglophones spoke in the 18th century, as in John Walker’s Critical Pronouncing Dictionary (1791), where he normatively condemns rhotic English. Then again, perhaps it is merely a storytelling expedient; look at the actors assembled to play Founding Fathers:

Standardization may have made practical sense, but the use of the rhotic sends a subtly different message than North American Standard English, and perhaps hints at the influence of David Crystal’s work on OP/EME.

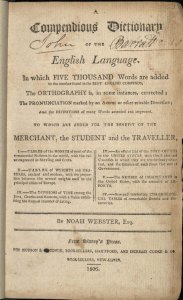

First page of Noah Webster’s Compendious Dictionary (1806)

Even among linguists, North American 18th century English has not been examined to the extent that EME has, with Beal going no further than to suggest “the contact between the various regional dialects of the English-speaking colonists and the languages of the Native Americans and of other European colonists” would have influenced pronunciation, but she is not conclusive as to what extent. Noah Webster in 1789 envisioned “a language in North America, as different from the future language of England, as the modern Dutch, Danish and Swedish are from the German or from one another” (cited in Mühleisen). From the beginning, too, American fiction was concerned with pronunciations, with Cooper sensitive to those which “disclosed class or origins,” as Schachterle noted. The word “Americanism,” in fact, was coined by John Witherspoon in 1781. Its entry in Webster’s Compendious Dictionary (1806) is “a love of America and preference of her interest.” As David Crystal points out, this was the first dictionary written in English to include words like butternut, caucus, checkers, chowder, constitutionality, hickory, opossum, skunk and succotash. It was also the first dictionary to give now-familiar American spellings to words like color and defense.

It is probably not a surprise that many of the words above have their origins in Native American languages. Black and Native voices (and use of dialect) are somewhat rare in media depictions of the Revolutionary period, notable exceptions being The Last of the Mohicans, with its heroes (“Hawkeye,” Uncas, and Chingachgook, played by Daniel Day-Lewis, Eric Schweig, and Russell Means, respectively), as part of an extended, multi-racial family unit, speaking with a uniform Standard North American accent:

and Ubisoft’s smash video game, Assassin’s Creed III (2012).

The hero of this Xbox/Playstation game is Connor/Ratohnhaké:ton (Noah Watts), half-British, half-Mohawk, who speaks Mohawk as well as English (again, no Tonto talk here), as taught by the project’s language consultant, Akwiratekha’ Martin. However, again ignoring historical realities like the Sullivan campaign, the villains are British redcoats, echoing the storyline set up by The Patriot (Connor’s village is burned and his parents are killed by a British officer who sneers, “You are a nothing, living in the dirt like animals.”) In a making-of featurette, the creators of Assassin’s Creed III note that it has more than two hours of “cinematics,” a concept that suggests that the game will be a more potent window into history for its users than film, television, radio, or books. While it is positive that the game inaugurates a Native American action hero role model, it is disappointing that it recycles “the British are baddies” dialect trope.

In media like cartoons, video games, and audio drama, dialect supplies us with many clues about characters and what we should think and feel about them. Class is still very much implicit in accents in Britain, and every time we open our mouths we display characteristics about ourselves, whether feigned or not. When mass media-makers produce historical drama, they make choices. Despite the United States’ and the United Kingdom’s “special relationship,” the “British are baddies” trope remains. Its continued use and the future choices made by media-makers have much to say about Anglo-American relations and conventions in fiction today.

If, as suggested by several linguists identified in this article, children very quickly pick up conventions of who is “bad” via what they sound like, it behooves us to pay careful attention to the way mass media uses voices and what norms these establish, for listeners young and old. Also, what accents filmmakers use for past accents may profoundly influence who can hear themselves as “American” in the present moment–one important reason why Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton resonated with contemporary audiences. If teacher Laura Amico in the Cliffside Park school district in New Jersey has established that her pupils should “speak American,” what does this mean (besides the fact she expects them to speak English not Spanish)? Should they, for example, speak like President Trump, who uses a New York Queens accent which, according to Jeff Guo, connotes “competence, aggressiveness and directness” despite the fact its speaker comes from a privileged background? As Guo suggests, the way we speak is at least as important as what we say. In response to reports that Trump mocked the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, by imitating his accent, Congressman Raja Krishnamoorthi published a statement saying, “Americans are not defined by their accents, but by their commitment to this nation’s values and ideals.” That, perhaps, is speaking American?

—

Featured Image: Arno Victor Dorian, Assassin’s Creed Unity: Leon Chiro Cosplay Art

—

With thanks to Kenneth Longden and Matthew Kilburn

—

Leslie McMurtry has a PhD in English (radio drama) and an MA in Creative and Media Writing from Swansea University. Her work on audio drama has been published in The Journal of Popular Culture, The Journal of American Studies in Turkey, and Rádio-Leituras. Her radio drama The Mesmerist was produced by Camino Real Productions in 2010, and she writes about audio drama at It’s Great to Be a Radio Maniac.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Magical Post-Horn: A Trip to the BBC Archive Centre in Perivale–Leslie McMurtry

Speaking “Mexican” and the use of “Mock Spanish” in Children’s Books (or Do Not Read Skippyjon Jones)–Inés Casillas

Sounding Out! Podcast #40: Linguicide, Indigenous Community and the Search for Lost Sounds